Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Intestinal and Rectal Disorders

Ulcerative Colitis - Inflammatory Bowel Disease

ULCERATIVE

COLITIS

Ulcerative

colitis is a recurrent ulcerative and inflammatory dis-ease of the mucosal and

submucosal layers of the colon and rec-tum. The incidence of ulcerative colitis

is highest in Caucasians and people of Jewish heritage (Yamada et al., 1999).

The peak in-cidence is between 30 and 50 years of age. It is a serious disease,

accompanied by systemic complications and a high mortality rate. Eventually,

10% to 15% of the patients develop carcinoma of the colon.

Pathophysiology

Ulcerative

colitis affects the superficial mucosa of the colon and is characterized by

multiple ulcerations, diffuse inflammations, and desquamation or shedding of

the colonic epithelium. Bleed-ing occurs as a result of the ulcerations. The

mucosa becomes edematous and inflamed. The lesions are contiguous, occurring

one after the other. Abscesses form, and infiltrate is seen in the mucosa and

submucosa with clumps of neutrophils in the crypt lumens (ie, crypt abscesses).

The disease process usually begins in the rectum and spreads proximally to

involve the entire colon. Eventually, the bowel narrows, shortens, and thickens

because of muscular hypertrophy and fat deposits.

Clinical Manifestations

The

clinical course is usually one of exacerbations and remissions. The predominant

symptoms of ulcerative colitis are diarrhea, lower left quadrant abdominal

pain, intermittent tenesmus, and rectal bleeding. The bleeding may be mild or

severe, and pallor results. The patient may have anorexia, weight loss, fever,

vomit-ing, and dehydration, as well as cramping, the feeling of an ur-gent need

to defecate, and the passage of 10 to 20 liquid stools each day. The disease is

classified as mild, severe, or fulminant, depending on the severity of the

symptoms. Hypocalcemia and anemia frequently develop. Rebound tenderness may

occur in the right lower quadrant. Extraintestinal symptoms include skin

le-sions (eg, erythema nodosum), eye lesions (eg, uveitis), joint

ab-normalities (eg, arthritis), and liver disease.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The

patient should be assessed for tachycardia, hypotension, tachyp-nea, fever, and

pallor. Other assessments include the level of hy-dration and nutritional

status. The abdomen should be examined for characteristics of bowel sounds,

distention, and tenderness. These findings assist in determining the severity

of the disease.

The

stool is positive for blood, and laboratory test results re-veal a low

hematocrit and hemoglobin concentration in addition to an elevated white blood

cell count, low albumin levels, and an electrolyte imbalance. Abdominal x-ray

studies are useful for de-termining the cause of symptoms. Free air in the

peritoneum and bowel dilation or obstruction should be excluded as a source of

the presenting symptoms. Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy and barium enema are

valuable in distinguishing this condition from other diseases of the colon with

similar symptoms. A barium enema may show mucosal irregularities, focal

strictures or fistu-las, shortening of the colon, and dilation of bowel loops.

En-doscopy may reveal friable, inflamed mucosa with exudate and ulcerations.

This procedure assists in defining the extent and severity of the disease. CT

scanning, magnetic resonance imag-ing, and ultrasound can identify abscesses

and perirectal in volvement. Leukocyte scanning is useful when se-vere colitis

prohibits the use of endoscopy to determine the ex-tent of inflammation.

Careful

stool examination for parasites and other microbes is performed to rule out

dysentery caused by common intestinal or-ganisms, especially Entamoeba histolytica and Clostridium difficile.

Complications

Complications

of ulcerative colitis include toxic megacolon, per-foration, and bleeding as a

result of ulceration, vascular engorge-ment, and highly vascular granulation

tissue. In toxic megacolon, the inflammatory process extends into the

muscularis, inhibiting its ability to contract and resulting in colonic

distention. Symp-toms include fever, abdominal pain and distention, vomiting,

and fatigue. Colonic perforation from toxic megacolon is asso-ciated with a

high mortality rate (15% to 50%) (Grendell et al., 1998). If the patient with

toxic megacolon does not respond within 24 to 48 hours to medical management

with nasogastric suction, intravenous fluids with electrolytes,

corticosteroids, and antibiotics, surgery is required. Total colectomy is

indicated. For many patients, surgery becomes necessary to relieve the effects

of the disease and to treat these serious complications; an ileostomy usually

is performed. The surgical procedures involved and the care of patients with

this type of fecal diversion are discussed later.

Patients

with IBD also have a significantly increased risk of os-teoporotic fractures

due to decreased bone mineral density. Corti-costeroid therapy may also

contribute to the diminished bone mass.

Medical Management of Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Medical

treatment for regional enteritis and ulcerative colitis is aimed at reducing

inflammation, suppressing inappropriate im-mune responses, providing rest for a

diseased bowel so that heal-ing may take place, improving quality of life, and

preventing or minimizing complications.

Most

patients maintain long-term well-being interspersed with short intervals of

illness (Hanauer, 2001). Management depends on the disease location, severity,

and complications.

NUTRITIONAL THERAPY

Oral

fluids and a low-residue, high-protein, high-calorie diet with supplemental

vitamin therapy and iron replacement are prescribed to meet nutritional needs,

reduce inflammation, and control pain and diarrhea. Fluid and electrolyte

imbalances from dehydration caused by diarrhea are corrected by intravenous

therapy as neces-sary if the patient is hospitalized or by oral supplementation

if the patient can be managed at home. Any foods that exacerbate diar-rhea are

avoided. Milk may contribute to diarrhea in those with lactose intolerance.

Cold foods and smoking are avoided because both increase intestinal motility.

Parenteral nutrition may be indicated.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Sedatives

and antidiarrheal and antiperistaltic medications are used to minimize

peristalsis to rest the inflamed bowel. They are continued until the patient’s

stools approach normal frequency and consistency.

Aminosalicylate

formulations such as sulfasalazine (Azulfidine) are often effective for mild or

moderate inflammation and are used to prevent or reduce recurrences in

long-term maintenance regi-mens. Newer sulfa-free aminosalicylates (eg,

mesalamine [Asacol, Pentasa]) have been developed and shown effective in

preventing and treating recurrence of inflammation (Wolfe, 2000). Anti-biotics

are used for secondary infections, particularly for purulent complications such

as abscesses, perforation, and peritonitis.

Corticosteroids

are used to treat severe and fulminant disease. These corticosteroids (eg,

prednisone) can be administered orally in outpatient treatment or parenterally

in hospitalized patients. Topical (ie, rectal administration) corticosteroids

are also widely used in the treatment of distal colon disease. When the dosage

of corticosteroids is reduced or stopped, the symptoms of disease may return.

If corticosteroids are continued, adverse sequelae such as hypertension, fluid

retention, cataracts, hirsutism (ie, abnormal hair growth), adrenal

suppression, and loss of bone density may develop.

Immunomodulators

(eg, azathioprene [Imuran], 6-mercap-topurine, methotrexate, cyclosporin) have

been used to alter the immune response (Wolfe, 2000). The exact mechanism of

action of these medications in treating IBD is unknown. They are used for

patients with severe disease who have failed other therapies. These medications

are useful in maintenance regimens to prevent relapses. Newer biologic

therapies are being studied, and it is hoped that they will lead to improvement

in the treatment of pa-tients with chronically active disease (Yamada et al.,

1999).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

When

nonsurgical measures fail to relieve the severe symptoms of IBD, surgery may be

recommended. The most common indications for surgery are medically intractable

disease, poor quality of life, or complications from the disease or medical

ther-apy (Wolfe, 2000).

More

than one half of all patients with regional enteritis require surgery at some

point. Recurrence of inflammation and disease after surgery in regional

enteritis is inevitable. The rate of recur-rence after surgery is 20% to 40% in

the first 5 years. Patients younger than 25 years of age have the highest

recurrence rate. Surgery for regional enteritis is indicated for refractory

disease or complications (Wolfe, 2000). The procedure of choice is a total

colectomy and ileostomy.

A

newer surgical procedure developed for patients with severe regional enteritis

is intestinal transplant. This technique is now available to children and to

young and middle-age adults who have lost intestinal function from disease.

Although not a cure, this procedure may eventually provide improvement in

quality of life for some who are terminally ill. The technical and immunologic

problems with this procedure remain formidable, and the costs and mortality

rates remain high (Wolfe, 2000).

Approximately

15% to 20% of patients with ulcerative coli-tis require surgical intervention

(Tierney et al., 2000). Indica-tions for surgery include lack of improvement

and continued deterioration, profuse bleeding, perforation, stricture

formation, and cancer. Surgical excision usually improves quality of

life.Proctocolectomy with ileostomy (ie, complete excision of colon, rectum,

and anus) is recommended when the rectum is severely involved.

One

type of surgical technique that can be helpful is stric-tureplasty, in which

the blocked or narrowed section of the bowel is widened, leaving the bowel

intact. If a lesion can be delineated in regional enteritis or if a

complication has occurred, the lesion is resected, and the remaining portions

of the bowel are anasto-mosed. Surgical removal of up to 50% of the small bowel

usually can be tolerated. Other types of surgical procedures, known as fecal

diversions, are discussed later.

Total Colectomy With Ileostomy.

Anileostomy, the surgical cre-ation of an

opening into the ileum or small intestine (usually by means of an ileal stoma

on the abdominal wall), is commonly per-formed after a total colectomy (ie,

excision of the entire colon). It allows for drainage of fecal matter (ie,

effluent) from the ileum to the outside of the body. The drainage is very mushy

and oc-curs at frequent intervals. Nursing management of the patient with an ileostomy

is discussed in a later section.

Total Colectomy With Continent Ileostomy.

Another procedureinvolves the removal of the entire colon and creation

of the con-tinent ileal reservoir (ie, Kock pouch). This procedure eliminates

the need for an external fecal collection bag. Approximately 30 cm of the

distal ileum is reconstructed to form a reservoir with a nipple valve that is

created by pulling a portion of the terminal ileal loop back into the ileum. GI

effluent can accumulate in the pouch for several hours and then be removed by

means of a catheter inserted through the nipple valve. The major problem with

the Kock pouch is malfunction of the nipple valve, which occurs in about 20% of

the patients (Yamada et al., 1999).

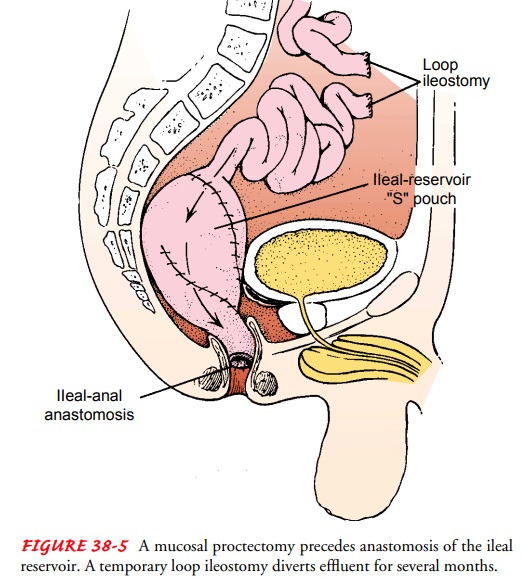

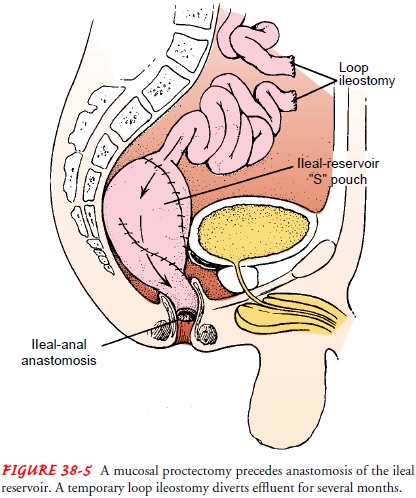

Total Colectomy With Ileoanal Anastomosis.

A total colectomywith ileoanal anastomosis is another surgical procedure

that elim-inates the need for a permanent ileostomy. It establishes an ileal

reservoir, and anal sphincter control of elimination is retained. The procedure

involves connecting a portion of the ileum to the anus (ie, ileoanal

anastomosis) in conjunction with removal of the colon and the rectal mucosa

(ie, total abdominal colectomy and mucosal proctectomy) (Fig. 38-5). A

temporary diverting loop ileostomy is constructed at the time of surgery and

closed about 3 months later.

With

ileoanal anastomosis, the diseased colon and rectum are re-moved, voluntary

defecation is maintained, and anal continence is preserved. The ileal reservoir

decreases the number of bowel move-ments by 50%, from approximately 14 to 20

per day to 7 to 10 per day. Nighttime elimination is gradually reduced to one

bowel movement. Complications of ileoanal anastomosis include irritation of the

perianal skin from leakage of fecal contents, stricture forma-tion at the

anastomosis site, and small bowel obstruction.

Nursing Management

Nursing management of patients with IBD may be medical, sur-gical, or both. Patients in the community setting or those recently diagnosed may primarily require education about diet and med-ications and referral to support groups. Hospitalized patients with long-standing or severe disease also require careful monitoring, parenteral nutrition, fluid replacement, and possibly emergent surgery. The surgical procedures may involve a fecal diversion, with attendant needs for physical care, emotional support, and extensive teaching about management of the ostomy.

Related Topics