Chapter: Psychology: Personality

The Trait Approach: Traits and the Environment

Traits and the Environment

It

seems plausible, then, that genes influence personality in a variety of ways—by

deter-mining the reactivity of neurotransmitter systems, the threshold for

activation in the amygdala, and more. But, as we have repeatedly noted, genetic

influence will emerge only if certain environmental supports are in place. In

addition, virtually any character-istic shaped by the genes is also likely to

be shaped by environmental factors. What are the environmental factors relevant

to the development of someone’s personality? Three sources of influence have

been widely discussed: cultures, families, and differences among members within

the same family.

CULTURAL EFFECTS

As

we have seen, the evidence is mixed on whether the Big Five dimensions are as

useful for describing personalities in Korea as they are in Kansas, as useful

in Niger as they are in Newport. But no matter what we make of this point, we

need to remember that the Big Five is simply a framework for describing how

people differ; if the framework is in fact universal, this simply tells us that

we can describe personalities in different cultures using the same (universal)

measuring system, just as we can measure objects of different sizes using the

same ruler. This still leaves open, however, what the personalities are in any

given culture—that is, what we will learn when we use our measuring system.

Scholars

have long suggested that people in different cultures have different

personalities—so that we can speak of a “German personality,” or a “typical

Italian,” and so on. One might fear that these suggestions amount to little

beyond stereotyping, and indeed, some scholars have argued that these

perceptions may be entirely illusory (McCrae & Terracciano, 2006). Mounting

evidence suggests, however, that there is a kernel of truth in some of these

claims about national character. For

example, one study has shown that there are differences from one country to the

next in how consci-entious people seem to be. These differences are manifest in

such diverse measures as pedestrians’ walking speed, postal workers’

efficiency, accuracy of public clocks, and even longevity in each of these

countries (Heine, Buchtel, & Norenzayan, 2008)!

Where

might these cultural differences in personality come from? One long-standing

hypothesis is that the key lies in how a group of people sustains itself,

whether through farming or hunting or trade (Barry, Child, & Bacon, 1959;

Hofstede, 2001; Maccoby, 2000). More recent models, in contrast, take a more

complex view, and sug-gest that cultural differences in personality—whether

between nations or across regions within a single nation—arise via a

combination of forces (Jokela, Elovainio, Kivimaki, & Keltikangas-Jarvinen,

2008; Rentfrow, Gosling, & Potter, 2008). These forces include historical

migration patterns, social influence, and environmental factors that

dynamically reinforce one another over time. To make this concrete, let’s

consider immigrants who first make their way to a new geographical region

(whether fleeing persecution or seeking prosperity). It seems unlikely that

these trailblazers will be a ran-dom sample of the larger population. Instead,

the mere fact that they decided to relo-cate suggests that they may be willing

to take risks and more open to new experiences in comparison to others who were

not willing to emigrate. This initial difference might then be magnified via

social influence—perhaps because the especially extraverted or open individuals

engaged in practices that shaped the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of those

around them.

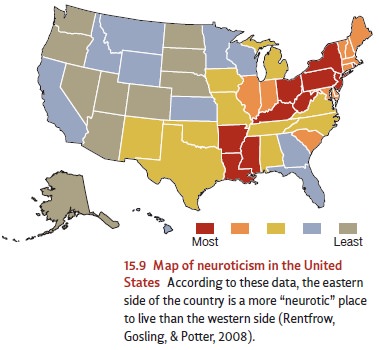

Arguments

like these may help us understand why different regions within the United

States often seem characterized by distinct personality types, with neuroticism

especially common in some of the mid-Atlantic states and openness to new

experience

common

in the Pacific Northwest. Indeed, one recent book (Florida, 2008) urges people

to seek out regions that have personalities compat-ible with their

own—providing yet another factor shaping regional or national personality:

People may move to an area because they believe (or hope) certain traits are

common there, and this selective migration can itself create or magnify

regional differences (Figure 15.9).

FAMILY EFFECTS

It

seems likely that another factor shaping personality is one’s family. If the

family environment does influence personality, we would expect a

A

similar message emerges from a study that compared the personality traits of

pairs of adult twins. Some of the twins had been reared within the same family;

others had been reared apart and had been separated for an average of over 30

years. Among the twins reared together the personality scores for identical

twins were, as usual, more highly correlated than the scores of fraternal twins,

with correlations of .51 and .23, respectively. Thus, greater genetic

resemblance (identical twins, remember, share all of their genes; fraternal

twins share only half of their genes) led to greater personality resemblance.

Amazingly, though, the twins who were reared apart and had been separated for

many years showed nearly the same pattern of results as twins who grew up

together. The correlations were .50 and .21 for identical and fraternal twins,

respectively. (Moloney, Bouchard, & Segal, 1991).

One

might have expected the correlations to be considerably lower for the traits of

the twins who had been raised apart, since they were reared in different family

environ-ments. That the results were nearly the same whether the twins were

raised together or apart speaks against granting much importance to the various

environmental factors that make one family different from the next (Bouchard,

1984; Bouchard et al., 1990; Tellegen et al., 1988; also see Turkheimer &

Waldron, 2000).

Some

authors have drawn strong conclusions from these data—namely, that the family

plays little role in shaping personality (J. R. Harris, 1998). We would urge

cau-tion, though, in making this sweeping claim. Most of the available evidence

comes from families whose socioeconomic status was working class or above, and

this range is rather limited. It does not include the environments provided by

parents who are unemployed or those of parents who abuse or neglect their

children. If the range had been broadened to include more obviously different

environments, between-family environmental differences would surely have been

demonstrated to be more important (Scarr, 1987, 1992).

WITHIN

– FAMILY EFFECTS

If—within

the range of environments studied—between-family environmental differ-ences are

less important than one might expect, what environmental factors do mat-ter?

According to Plomin and Daniels (1987), the key lies in how the environments

vary for different children within the same family. To be sure, children within

a family

share

many aspects of their objective environment. They have the same parents, they

live in the same neighborhood, they have the same religion, and so on. But the

environments of children within a family also differ in crucial ways. They have

different friends, teach-ers, and peer groups, and these can play an important

role in shap-ing how they behave. Moreover, various accidents and illnesses can

befall one child but not another, with potentially large effects on their

subsequent personalities. Another difference concerns the birth order of each

child, since the family dynamic is different for the first-born than it is for

later-born children (Figure 15.10). Some authors have suggested that birth

order may have a powerful influ-ence on personality, with later-borns being

more rebellious and more open to new experiences than first-borns (Sulloway,

1996).

Factors

like these suggest that the family environment may matter in shaping

per-sonality, but they indicate that we need to focus on within-family

differences rather than between-family factors, like the fact that one family

is strict and another lenient, or the fact that some parents value education

while others value financial achievement. Indeed, within-family factors may be

especially important since parents often do what they can to encourage

differences among their children; some authors have suggested that this is a

useful strategy for diminishing sibling rivalry (Schachter, 1982).

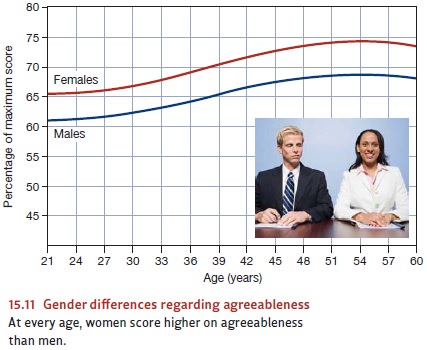

The

gender of the child also plays a role. A brother and sister grow up in the same

household, but are likely to be treated differently by their parents (not to

mention other relatives, teachers, and friends). This, too, will provide a

family influence shaping person-ality (although obviously these gender effects

reach well beyond the family), but will once again produce within-family

contrasts. In any case, this sort of differential treatment for men and women

may—especially when combined with the biological differences between the

sexes—help us understand why women score higher on the “agreeableness”

dimension of the Big Five (Figure 15.11; Srivastava, John, Gosling, &

Potter, 2003), and why women are less likely to be sensation-seekers

(Zuckerman, 1994). In this context, though, we should also note that many of

the popular conceptions about gender differ-ences in personality—which are

surprisingly robust across cultures (Heine, 2008)—are probably overstated; in

fact, women and men appear remarkably similar, on average, on many aspects of

personality (Feingold, 1994; J. S. Hyde, 2005).

Related Topics