Chapter: Psychology: Personality

The Trait Approach: The Big Five

The Big Five

An

unabridged English dictionary contains almost 18,000 personality-relevant terms

(Allport & Odbert, 1936). To reduce this list to manageable size, early

trait theorists put many of these words to the side simply because they were

synonyms, slang, or just uncommon words. Raymond Cattell, one of the pioneers

in this arena, gave this kind of shortened list of words to a panel of judges,

asking them to use these words to rate a group of people they knew well

(Cattell, 1957). Their ratings were compared to find out which terms were

redundant. This process allowed Cattell (1966) to eliminate the redundant

terms, yielding what he thought were the 16 primary personality dimensions.

Subsequent

investigators presented evidence from further analyses that several of

Cattell’s dimensions still overlapped, so they reduced the set still further. A

few investigators, such as Hans Eysenck (1967), argued that just two dimensions

were needed to describe all the variations in personality, although he later

added a third. Others argued that this was too severe a reduction, and, over

time a consensus has emerged around five major personality dimensions as the

basis for describing all personalities; this has led to a personality system

appropriately named the Big Five (D.

W. Fiske, 1949; Norman, 1963; Tupes & Christal, 1961).

The

Big Five dimensions are extraversion

(sometimes called extroversion), neuroticism

(sometimes labeled with its positive pole, emotional stability), agreeableness, conscientiousness, and

openness to experience (L. R. Goldberg, 2001; John & Srivastava,1999;

McCrae & Costa, 2003).* These dimensions seem useful for describing people

from childhood through old age (Allik, Laidra, Realo, & Pullman, 2004; McCrae

& Costa, 2003; Soto, John, Gosling, & Potter, 2008) in many different

cultural settings (John & Srivastava, 1999; McCrae & Costa, 1997;

McCrae & Terracciano, 2005; Yamagata et al., 2006). The Big Five traits

even seem useful in describing the personal-ities of other species, including

chimpanzees, dogs, cats, fish, and octopi (Gosling, 2008; Gosling & John,

1999; Weiss, King, & Figueredo, 2000).

What do these dimension labels mean? Extraversion means having an energetic approach toward the social and physical world. Extraverted people often feel positive emotion and tend to agree with statements like “I see myself as someone who is outgo-ing, sociable,” while people who are introverted (low in extraversion) tend to disagree with these statements. (This and the following items are from the Big Five Inventory: John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991).Neuroticism means being prone to negative emotion, and its opposite is emotional stability. This dimension is assessed by finding out whether people agree with statements like “I see myself as someone who is depressed, blue.” Agreeableness is a trusting and easygoing approach to others, as indicated by agreement with statements like “I see myself as someone who is generally trusting.” Conscientiousness means having an organized, efficient, and disciplined approach to life,as measured via agreement with statements like “I see myself as someone who does things efficiently.” Finally, openness to experience refers to unconventionality, intellectual curiosity, and interest in new ideas, foods, and activities. Openness is indicated by agreement with statements like “I see myself as someone who is curious about many different things.”

Notice

that the Big Five—like Cattell’s initial set of 16 dimen-sions—is cast in terms

of personality dimensions, and we identify someone’s personality by specifying

where he falls on each dimen-sion. This allows us to describe an infinite

number of combinations, or, to put it differently, an infinite number of

personality profiles created by different mixtures of the five basic

dimensions.

MEASUREMEN AND MEANING

As

we will see, personality theorists rely on many different types of data. To

measure where a person stands on each

of the Big

Five dimensions, researchers

typically use self- report data, employing measures such as

Costa and McCrae’s NEO- PI-R (1992)—asking people in essence to describe

themselves, or to indicate how much they agree with proposed statements that

might describe them. Self-report measures assume, though, that each of us

knows a

great deal about

our own beliefs,

emotions, and pastactions, and so can describe ourselves.

But is this assumption correct? What if people lack either the self-knowledge

or the honesty required for an accurate self-report (Dunning, Heath, &

Suls, 2004)?

To

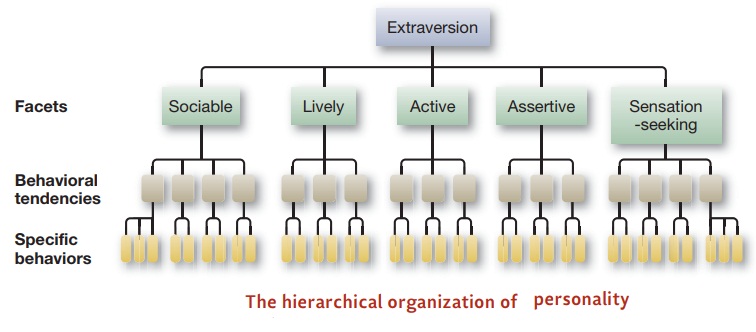

find out, one option is to collect data not just from the people we are

interested in, but also from others who know these people well. These informant data can come from parents,

teachers, coaches, camp counselors, fellow parishioners, and so on (Figure

15.1). Though informants’ perspectives are not perfect, they provide another

important win-dow onto the person, and across studies researchers have found that

self-report and informant data generally agree well in the case of ratings of

the Big Five (McCrae & Costa, 1987). It seems, then, that most people do

know themselves reasonably well—a point that is interesting for its own sake,

and also makes our assessment of traits rela-tively straightforward.

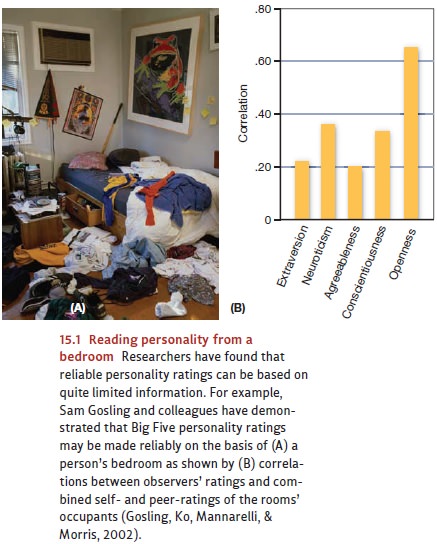

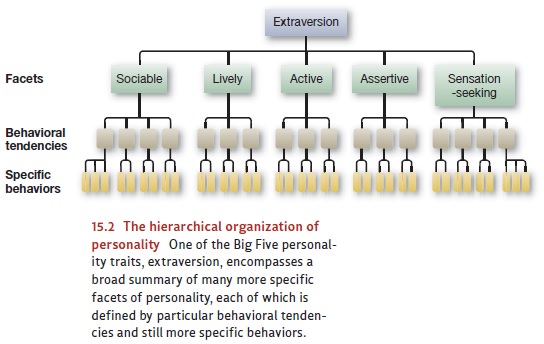

No

matter how they’re measured, the Big Five dimensions are probably best

concep-tualized in hierarchical terms, as shown in Figure 15.2. This figure

presents just one of the Big Five dimensions, extraversion, and shows that this

dimension is really a broad summary of many more specific facets of

personality. Each of these facets in turn is made up of even more specific

behavioral tendencies, which are themselves made up of specific behaviors. If

we choose terms higher in the hierarchy (e.g., the Big Five themselves), we

gain a more economical description with fewer, broader terms.

At

the same time, though, if we choose terms lower in the hierarchy, we gain

accu-racy, with the traits providing a more direct and precise description of

each person’s behavior (John & Srivastava, 1999). Thus, for example, if we

want to predict how a new

employee

will perform on the job, or predict how well a nurse will perform under stress,

we might want more than the overarching description provided by the Big Five

itself; we might want to zoom in for a closer look at the way the Big Five

traits can manifest themselves in a particular individual. One way to do this

is to use the Q-Sort, a set of 100 brief descriptions that a rater sorts into a

predetermined number of piles, corresponding to the degree to which they

describe a person (Block, 2008). There are also hundreds of more-specific

measures available, each seeking to describe a particu-lar aspect of who

someone is and how he or she behaves.

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES

Cattell

and the Big Five theorists developed their personality factors in English, and

they used mostly middle-class English-speaking subjects to validate their theories.

As discussed, though, cultures differ in how they view human nature. Are the

Big Five dimensions equally useful as we move from one culture to the next?

We

have already alluded to the fact that the Big Five dimensions do seem to

describe personalities in a wide range of cultures. More precisely, as we move

from one culture to the next, we still find that the trait labels people use to

describe each other can be “boiled down” to the same five dimensions (McCrae

& Costa, 1997; McCrae & Terracciano, 2005). There are, however, reasons

to be cautious about these findings. As one concern, instead of allowing

natives of a culture to generate and organize personality terms themselves

(Marsella, Dubanoski, Hamada, & Morse, 2000), most researchers simply administer

a test that was already developed using English-speaking subjects. This

approach may not allow people’s natural or routine understandings to emerge

(Greenfield, 1997), and so, even if these studies confirm the existence of the

Big Five dimensions in a population, they do not show us whether these are the

most frequently used categories in that culture, or whether they are useful in

predicting the same behaviors from one culture to the next.

In

fact, when participants have been allowed to generate personality terms on

their own, support for the cross-cultural generality of the Big Five has been

mixed. For example, when researchers explored the personality traits used by

Hong Kong and mainland Chinese samples, they found four factors that could be related

to the Big Five, but one factor that seemed to be uniquely Chinese, which

reflected interpersonal relatedness and harmony (Cheung, 2004; Cheung &

Leung, 1998; see Figure 15.3). In Spanish samples, seven factors seem best to

describe personality (Benet-Martinez, 1999), five of which map reasonably well

onto the Big Five. Other researchers have found three factors in Italian

samples (Di Blas, Forzi, & Peabody, 2000), and nine fac-tors bearing little

resemblance to the Big Five were used by students in Mexico (La Rosa &

Diaz-Loving, 1991). Thus, although the Big Five seem to be well established

among many cultures, there is room for debate about whether these dimensions

are truly universal.

Related Topics