Chapter: Psychology: Personality

Origins of the Social-Cognitive Approach

Origins of the Social-Cognitive Approach

Social-cognitive

theories vary in their specifics, but all derive from two long-standing

traditions. The first is the behavioral tradition, set in the vocabulary of

reward, punish-ment, instrumental responses, and observational learning . The second

is the cognitive view, which emphasizes the individual as a thinking being.

BEHAVIORAL ROOTS OF SOCIAL – COGNITIVE THEORIES

Central

to the behavioral tradition is a worldview that, in its extreme form, asserts

that virtually anyone can become anything given proper training. This American

“can-do” view was distilled in a well-known pronouncement by the founder of

American behaviorism, John B. Watson (Figure 15.29):

Give

me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them

up in and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any

type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief, and,

yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants,

tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors.

Watson’s

version of behaviorism was relatively primitive, but elements of his view are

still visible in subsequent theorizing within the social-cognitive perspective.

For example, Albert Bandura (like Watson) places a heavy emphasis on the role

of experience and learn-ing, and the potential each of us has for developing in

a variety of ways. But Bandura’s view of personality goes considerably beyond

Watson’s in its emphasis on the role we play as agents in fashioning our own

lives. According to Bandura (2001), we observe relation-ships between certain

actions (whether ours or others’) and their real-world consequences (rewards or

punishments), and from this we develop a set of internalized outcomeexpectations, which then come to

govern our actions.

In

addition, we gradually become aware of ourselves as agents able to produce

cer-tain outcomes, marking the emergence of a sense of self-efficacy, or a belief that one can perform the behaviors that

will lead to particular outcomes (Bandura, 2001, 2006). When a person’s sense

of self-efficacy is high, she believes that she can behave in ways that will

lead to rewarding outcomes. By contrast, when a person’s sense of self-efficacy

is low, she believes herself incapable, and she may not even try. Researchers

have found high self-efficacy beliefs to be associated with better social

relationships, work, and health outcomes (Bandura, 1997; 2001; Maddux, 1995;

Schwarzer, 1992). Likewise, self-efficacy beliefs about a particular task (“I’m

sure I can do this!”) are associated with success in that task. This attitude

leads to more persistence and a greater tolerance of frustration, both of which

contribute to better performance (Schunk, 1984, 1985).

Once

outcome expectations and beliefs about self-efficacy are in place, our actions

depend less on the immediate environment, and more on an internalized system of

self-rewards and self-punishments—our values and moral sensibilities. This

reliance on internal standards makes our behavior more consistent than if we

were guided simply by the exigencies of the moment, and this consistency is

what we know as personality. As seen from this view, personality is not just a

reflection of who the individual is, with a substantial contribution from biology.

Instead, in Bandura’s perspective, personality is a reflection of the

situations the person has been exposed to in the past, and the expectations and

beliefs that have been gleaned from those situations.

COGNITIVE ROOTS OF SOCIAL – COGNITIVE THEORIES

A

related tradition underlying social-cognitive theories of personality is the

cognitive view, first detailed by George Kelly (1955). Like many other

psychologists, Kelly acknowledged that people’s behavior depends heavily on the

situation. Crucially, though, he emphasized that much depends on their interpretations of the situation, which

Kelly called their personal constructs,

or the dimensions they use to organize their experience.

From

Kelly’s perspective, each person seeks to make sense of the world and find

meaning in it. To explain how people do this, Kelly used the metaphor of a

scientist who obtains data about the world and then develops theories to

explain what he has observed. These theories concern specific situations, but,

when taken together, consti-tute each individual’s personal construct system.

To assess these personal constructs, Kelly used the Role Construct Repertory

Test. This test asks people to list three key indi-viduals in their life, and

then to say how two of these three were different from a third. By repeating

this process with different groups of three ideas, traits, or objects, Kelly

was able to elicit the dimensions each person used (such as intelligence,

strength, or goodness) to make sense of the world.

Kelly’s

work is important in its own right, but his influence is especially visible in

the work of his former student, Walter Mischel. For Mischel (whom we met

earlier), the study of personality must consider neither fixed traits nor

static situations, but should focus instead on how people dynamically process

various aspects of their ever-changing world. Like Kelly, Mischel contends that

the qualities that form personality are essentially cognitive: different ways

of seeing the world, thinking about it, and interacting with it, all acquired

over the course of an individual’s life. But how should we conceptualize this

cognition, and, with it, the interaction between the individual and the

setting?

Mischel’s

answer to this broad question is framed in terms of each individual’s

cognitive-affective personality system (CAPS), which consists of five key

qualities on which people can differ. The first is the individual’s encodings, the set of construals by

which the person interprets inner and outer experiences. Second, individuals

develop expectancies and beliefs about

the world, which include the outcome expectations andsense of self-efficacy

stressed by Bandura. Third, people differ in their affects—that is, their emotional responses to situations. Fourth,

they differ in their goals and values,

the set of outcomes that are considered desirable. Finally, CAPS includes the

individual’s competencies and

self-regulatory plans, the way an individual regulates her own behaviorby

various self-imposed goals and strategies (Mischel, 1973, 1984, 2004; Mischel

& Shoda, 1995, 1998, 2000).

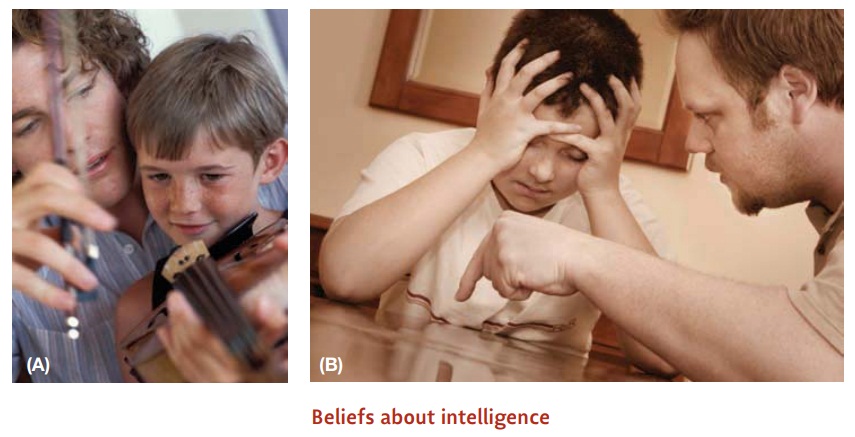

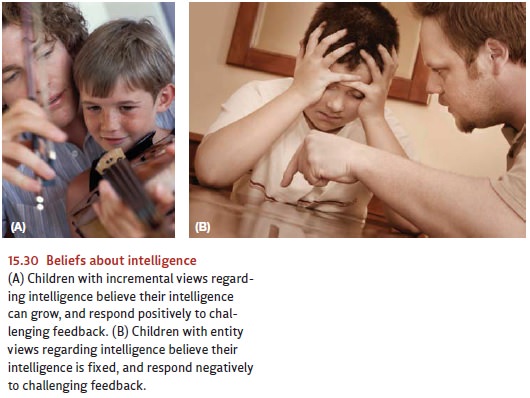

Other

researchers have filled in many details about what these various beliefs

involve. For example, Carol Dweck and

her colleagues have argued that people differ in their fundamental assumptions

about their own abilities (Dweck, 1999, 2006; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Molden

& Dweck, 2006). Some people assume their abilities are relatively fixed and

unlikely to change in the future. In con-trast to this entity view, others hold an incremental

view—assuming their abilities can change and grow in response to new

experience or learning (Figure 15.30). These assumptions turn out to be rather

important, because people with the incremental view are more willing to

confront challenges and better able to bounce back from frustration (Dweck,

2009). Evidence comes from many sources, including studies that have tried to

shift people’s thinking from the entity view to the incremental view. In one

study, Blackwell, Trzesniewski, and Dweck (2007) randomly assigned junior high

school stu-dents either to a regular study skills group or to an experimental

condition that taught students that the brain is like a muscle and can get

stronger with use. Compared to

those

in the study skills group, those in the experimental group showed increased

moti-vation and better grades.

These

differences in belief are another point in which cultures differ. Evidence

sug-gests, for example, that Americans tend toward the entity view, while the

Japanese tend toward an incremental view. This is reflected in the belief among

many students in the United States that the major influence on intelligence is

genetics; Japanese students, in contrast, estimate that the majority of intelligence

is due to one’s efforts (Heine et al., 2001). This result is likely related to

another finding we mentioned earlier: Americans tend to perceive themselves as

consistent in their behaviors as they move from one situation to the next, a

view similar to the entity view of intelligence, which emphasizes the stability

of one’s abilities. Some other cultures put less emphasis on personal

consistency, leaving them ready to embrace the potential for growth and change

at the heart of the incremental view.

Related Topics