Chapter: Psychology: Personality

The Humanistic Approach: Positive Psychology

Positive Psychology

Modern

researchers have taken heed of another insight offered by Maslow, Rogers, and

other humanists, who enjoined psychologists not to focus so much on deficiency

and pathology. Instead, these early humanists emphasized that humans also have

positive needs—to be healthy and happy, and to develop their potential. These

points underlie a relatively new movement called positive psychology.

In

the last decade or so, there has been a tremendous burst of research activity

that has sought scientifically to examine optimal human functioning (C.

Peterson, 2006). The focus of this research has been on positive subjective experiences, such as happiness, fulfill-ment,

and flow; positive individual traits,

including character strengths, values, and inter-ests; and positive social institutions, such as families, schools,

universities, and societies. In the next sections, we consider what positive

psychology has found concerning positive states and positive traits.

POSITIVE STATES

Novelists,

philosophers, and social critics have all voiced their views about what

hap-piness is and what makes it possible. Recently, academic psychologists have

also entered this discussion (e.g., Ariely, 2008; Gilbert, 2006; Haidt, 2006;

Lyubomirsky, 2008; B. Schwartz, 2004). What has research taught us about

happiness?

One

intriguing finding concerns the notion of a happiness set point, a level that appears to be heavily influenced by

genetics (Lykken & Tellegen, 1996) and is remark-ably stable across the

lifetime—and thus relatively independent of life circumstances. What produces

this stability? The key may be adaptation, the process through which we grow

accustomed to (and cease paying attention to) any stimulus or state to which we

are continually exposed. One early demonstration of this point comes from a

study that compared the sense of well-being in people in two rather different

groups. One group included individuals who had recently won the lottery; the

other was a group of para-plegics (Brickman, Coates, & Janoff-Bullman,

1978). Not surprisingly, the two groups were quite different in their level of

happiness soon after winning the lottery or losing the use of their limbs. When

surveyed a few months after these events, however, the two groups were similar

in their sense of contentment with their lives—an extraordinary testimony to

the power of adaptation and to the human capacity for adjusting to extreme

circumstances.

Adaptation

is a powerful force, but we must not overstate its role. Evidence suggests that

everyone tends to return to their happiness set point after a change (positive

or negative) in circumstances, but there are large individual differences in

how rapid and complete this return is. Thus, some people show much more of a

long-term effect of changes in marital status (Lucas, Clark, Georgellis, &

Diener, 2003) or long-term dis-ability (Lucas, 2007). Clearly, set points are

not the whole story; circumstances matter as well—more for some people than for

others.

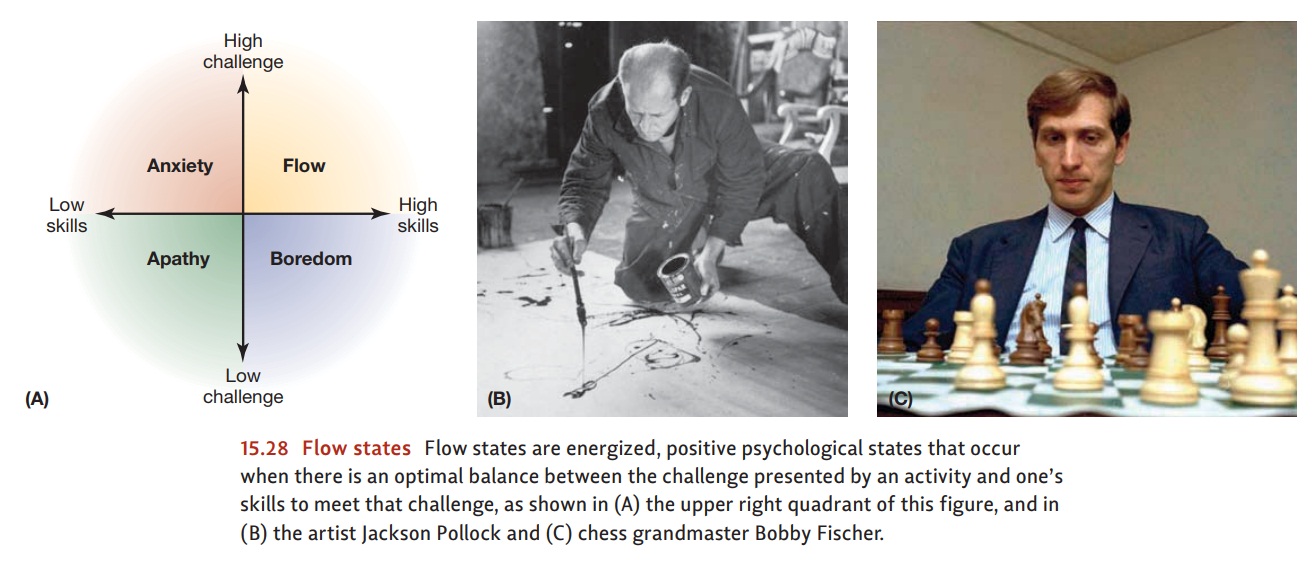

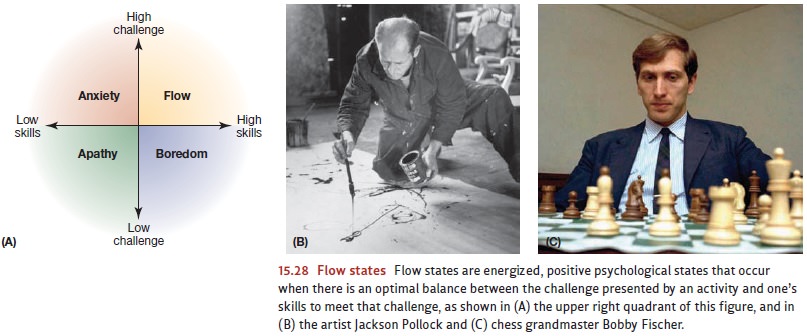

So

far, we have focused on what positive psychologists have been learning about

happi-ness, but they are also concerned with other positive states, such as the

energy and focus that are evident when the individual is fully engaged by what

she is doing. Csikszentmihalyi (1990) has examined such states by studying the

experiences of highly creative artists. He found that the painters he studied

became so immersed in their painting that they lost themselves in their work,

becoming temporarily unaware of hunger, thirst, or even the pas-sage of time.

Csikszentmihalyi called the positive state that accompanied the artists’

paint-ing “flow,” and he documented that far from being unique to artists, the

same sort of highly immersed and intrinsically rewarding state is evident in

rock climbers, dancers, and chess players (Figure 15.28). By systematically

studying people as they work and play,

Csikszentmihalyi

has found that flow is most likely to be experienced when there is an opti-mal

balance between the challenge presented by an activity and one’s skills to meet

that challenge. If the level of challenge is too low for one’s ability, one

feels bored. If the level of challenge is too high for one’s ability, one feels

anxiety. But if the challenge is just right— and one feels that the activity is

voluntarily chosen—one may experience flow.

POSITIVE TRAITS

Positive

psychologists have been concerned not just with positive states, like feeling

happy; they have also been concerned with positive traits—what we might think

of broadly as being a good person (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). This

interest has aligned them to some degree with the trait approach. However,

positive psychologists emphasize delineating a set of narrower and more

specific traits, namely, the “positive” or “desirable” traits.

Defining

and understanding these traits has been a central concern since the earli-est

days of psychology (James, 1890), but the topic was set aside as too

philosophical and value-laden for many years. Only in the past decade has the

systematic exposition of positive traits again come to the fore. One notable

effort, led by Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman, has focused on

developing a classification of characterstrengths

(Peterson and Seligman, 2004)—personal characteristics that (1)

contributeto a person’s happiness without diminishing the happiness of others,

(2) are valued in their own right, rather than as a means to an end, (3) are

trait-like and show variation across people, (4) are measurable using reliable

instruments, and (5) are evident across cultures, rather than specific to one

or a few cultures (C. Peterson, 2006).

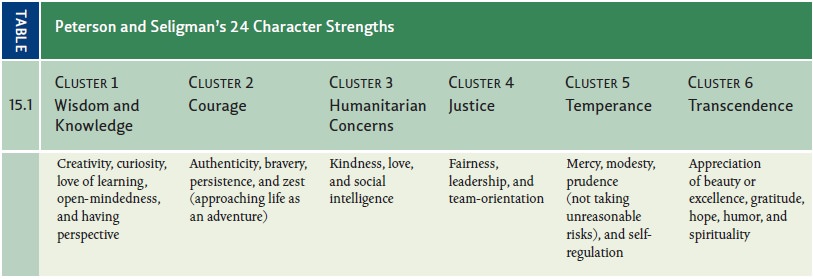

Peterson

and Seligman have identified 24 character strengths with these attributes,

organized into six clusters, as shown in Table 15.1. The first cluster of

character strengths centers around wisdom and knowledge; the second cluster

centers around courage; the third cluster centers around humanitarian concerns;

the fourth cluster centers around justice; the fifth cluster centers around

temperance, defined by an absence of excess; and the final cluster centers

around transcendence.

This

is a broad list—but may not be broad enough. For example, other researchers

have emphasized a role for optimism—a generalized expectation of desirable

rather than unde-sirable outcomes (Scheier & Carver, 1985). Another

important character strength is resilience,

which refers to surviving and even thriving in the face of

adversity—includingsuch extreme circumstances as serious illness, hostile

divorce, bereavement, and even rape

and

the ravages of war. These positive tendencies appear to be associated with a

number of important life outcomes, such as greater success at work, with

friends, and in marriage (Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005). The strengths

also matter for one’s physiological functioning and health (Ryff et al., 2006;

Salovey, Rothman, Detweiler, & Steward, 2000). For example, people who are

generally optimistic also have a better-functioning immune system and so are

more resistant to problems that range from the common cold to serious illness

(Pressman & Cohen, 2005; Segerstrom, 2000).

Related Topics