Chapter: Psychology: Personality

The Humanistic Approach: The Self

The

Self

This

discussion of self-actualization raises an important question: What exactly is

the self that the humanists

talked about, and where

does it come

from? More than

a century ago—well before

the humanists such

as Maslow and

Rogers came onto

the scene— William James (1890;

Figure 15.23) distinguished two aspects of the self, which he called the “I”

and the “me.” The “I” is the self that thinks, acts, feels, and believes. The

“me,” by contrast, is the set of physical and psychological attributes and

features that define who

you

are as a person. These include the kind of music you like, what you look like,

and the activities that currently give your life meaning. Half a century after

James first made this distinction, the humanist Carl Rogers used similar

language to talk about how the self-concept develops in early

childhood and eventually comes

to include one’s

sense of oneself—the

“I”—as an agent

who takes actions and makes

decisions. It also includes one’s sense of oneself as a kind of object— the

“me”—that is seen and thought about, liked or disliked (C. R. Rogers, 1959,

1961). Indeed, the self-concept was

such an important

aspect of Rogers’

approach that he referred to his theory as self theory, an

approach that continues to inspire contempo-

rary researchers

who seek to explain the

motives that activate

and support human behavior (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

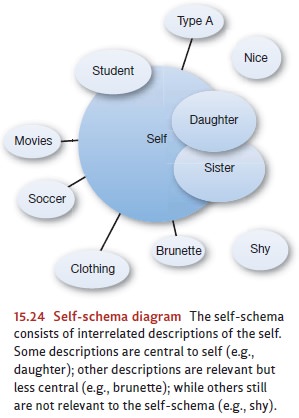

SELF - SCHEMA

For

each of us, our sense of self is a key aspect of our personality, and each of

us has a set of beliefs about who we are and who we should be, and a body of

knowledge about our val- ues and our past behaviors. This knowledge about

ourselves constitutes, for each person, a

self-schema(Markus, 1977; Figure 15.24). This

schema is not just a passive record of ourprior experiences; instead, the

schema actively shapes our behaviors, perceptions, and emo-tions. For example,

a person might have a schema of himself as a smart person who does well at

school. This self-schema will make certain situations, such as academic tests,

seem more important and consequential. The self-schema will also guide many of

his choices, such as opting to attend a more rigorous college rather than a

“party school” or spending the extra hour polishing a term paper rather than heading

off to get coffee with friends.

The

self-schema is not just a random list of characteristics. Instead, it is a

highly organized (although not always entirely consistent) narrative about who

one is. McAdams and colleagues (McAdams, 1993, 2001; McAdams & Pals, 2006)

refer to such personal narratives as personal

myths—in essence, “stories” that provide a sense of direction and meaning

for our lives. Moreover, given this important role for these nar-ratives, it

cannot be surprising that these narratives are resistant to change, and, in

fact, studies have shown that even people with negative self-concepts

tenaciously cling to these views, and seek out others who will verify these

views (Swann, Rentfrow, & Guinn, 2002).

Information

relevant to our self-schema is also given a high priority. For example, in

sev-eral studies, people have been shown a series of trait words and asked to

make simple judg-ments regarding these words (e.g., Is the word in capital

letters? Is it a positive word? Does it describe me?). When asked later to

remember the traits that they previously saw, partici-pants were more likely to

recall words presented in the “Does it describe me?” condition than in the

other conditions, suggesting that material encoded in relationship to the self

is better remembered (T. B. Rogers, Kuiper, & Kirker, 1977). These findings

are buttressed by neuroimaging studies that show the portions of the medial

prefrontal cortex are particu-larly active when people are engaged in

self-referential processes (as compared to when they are making judgments about

how the words are written, whether the words are good or bad, or even whether

they are characteristic of a friend; Heatherton et al., 2006).

Interestingly,

people seem to have schemas not only for who they are now, their actualselves, but also for who they may

be in the future—mental representations of

possible selves (Markus & Nurius, 1986; Figure 15.25). These include a

sense of theideal self that one would

ideally like to be (e.g., someone who saves others’ lives), and the ought self that one thinks one should be

(e.g., someone who never lies or deceives others) (E. T. Higgins, 1997).

According to E. Tory Higgins, when we compare our actual self to our ideal

self, we become motivated to narrow the distance between the two, and we

develop what he calls a promotion focus.

When we have this sort of focus, we actively pursue valued goals—a pursuit that

results in pleasure. In contrast, when we compare our actual self to our ought

self, we become motivated to avoid doing harm, and we develop what Higgins

calls a prevention focus. This kind

of focus is associated with feelings of relief.

Notice,

therefore, that schemas are not just dispassionate observations about

our-selves; instead, they often have powerful emotions attached to them and can

be a compelling source of motivation. This is why the schemas are typically

thought of as an aspect of “hot”

cognition (emotional and motivational) rather than “cold” cognition (dispassionate and analytical).

SELF -

ESTEEM AND SELF - ENHANCEMENT

The

“hot” nature of self-schemas is also evident in the fact that these schemas

play a pow-erful role in shaping a person’s self-esteem—a broad assessment that reflects the relative balance

of positive and negative judgments about oneself (Figure 15.26). Not

surprisingly, self-esteem is not always based on objective self-appraisals.

Indeed, people in Western

cultures

seem highly motivated to view themselves as different from and superior to

other people—even in the face of evidence to the contrary (Sedikides &

Gregg, 2008). This is manifest, for example, in the fact that most Americans

judge themselves to be above average on a broad range of characteristics (see

Harter, 1990). Thus, in 1976–1977 the College Board asked 1 million high-school

students to rate themselves against their peers on leadership ability. In

response, 70% said they were above average, and only 2% thought they were

below. Similar findings have been obtained in people’s judgments of talents

ranging from managerial skills to driving ability (see Dunning, Meyerowitz,

& Holzberg, 1989). And it is not just high-school students who show these

effects. One study of university pro-fessors found that 94% believed they were

better than their colleagues at their jobs (Gilovich, 1991).

What

is going on here? Part of the cause lies in the way we search our memories in

order to decide whether we have been good leaders or bad, good drivers or poor

ones. Evidence suggests that this memory search is often selective, showcasing

the occasions in the past on which we have behaved well and neglecting the

occasions on which we have done badly—leading, of course, to a self-flattering

summary of this biased set of events (Kunda, 1990; Kunda, Fong, Sanitioso,

& Reber, 1993).

In

addition, people seem to capitalize on the fact that the meanings of these

traits— effective leader, good at getting along with others—are often

ambiguous. This ambigu-ity allows each of us to interpret a trait, and thus to

interpret the evidence, in a fashion that puts us in the best possible light.

Take driving ability. Suppose Henry is a slow, careful driver. He will tend to

think that he’s better than average precisely because he’s slow and careful.

But suppose Jane, on the other hand, is a fast driver who prides her-self on

her ability to whiz through traffic and hang tight on hairpin turns. She will

also think that she’s better than average because of the way she’s defined driving

skill. As a result, both Henry and Jane (and, indeed, most drivers) end up

considering themselves above average. By redefining success or excellence, we

can each conclude that we are successful (Dunning & Cohen, 1992; Dunning et

al., 1989).

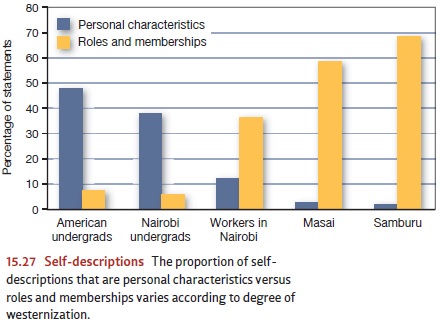

CULTURE

AND THE SELF

Although

the self-schema is important for all of us, the content of the schema varies from individual to individual and, it

seems, from one culture to the next. When they think about themselves,

Americans tend to think about their broad, stable traits, traits that apply in

all settings, such as athletic, disorganized, and creative. Things are

differ-ent for people living in interdependent, collectivist cultures. They

also view themselves as having certain traits, but only in specific situations,

and so their self-descriptions tend to emphasize the role of the situation,

such as quiet at parties, or gentle with their parents (Ellemers, Spears, &

Dossje, 2002; D. Hart, Lucca-Irizarry, & Damon, 1986; Heine, 2008).

Similarly, people in interdependent cultures tend to have self-concepts that

emphasize their social roles, and so, when asked to complete the statement “I

am . . . ,” Japanese students are more likely to say things like “a sister” or

“a student,” whereas American students are more likely to mention traits like

“smart” or “athletic” (Cousins, 1989). Similar differences can show up within a

single culture. Thus, as shown in Figure 15.27, Kenyans who were least

westernized overwhelmingly described themselves in terms of roles and memberships

and mentioned personal characteristics such as traits only 2% of the time. By

contrast, Kenyans who were most westernized used trait terms nearly 40% of the

time, and only slightly less than American under-graduates (Ma &

Schoeneman, 1997).

There

is also variation from one culture to the next in how people evaluate

them-selves. In individualistic cultures, people seek to distinguish themselves

through personal achievement and other forms of self-promotion, with the result

of increased self-esteem. In collectivistic cultures, on the other hand, any

form of self-promotion threatens the relational and situational bonds that glue

the society together. Indeed, to be a “good” person in these cultures, one should

seek to be quite ordinary—a strategy that results in social harmony and meeting

collective goals, not increased self-esteem (Kitayama, Markus, Matsumoto, &

Norasakkunkit, 1997; Pyszczynski, Greenberg, Solomon, Arndt, & Schimel,

2004). For them, self-aggrandizement brings disharmony, which is too great a

price to pay. Evidence for this conclusion comes from a study in which American

and Japanese college students were asked to rank their abilities in areas

ranging from math and memory to warmheartedness and athletic skill. The

American students showed the usual result: Across all the questions, 70% rated

them-selves above average on each trait. But among the Japanese students, only

50% rated themselves above average, indicating no self-serving bias, and perhaps

pointing instead to a self-harmonizing one (Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Takata,

1987; also Dhawan, Roseman, Naidu, & Rettek, 1995).

Related Topics