Chapter: Psychology: Personality

The Trait Approach: The Consistency Controversy

The

Consistency Controversy

Whether

they endorse the Big Five dimensions or not, trait theorists agree that

individ-uals’ personalities can be described in terms of stable and enduring

traits. After all, when we say that someone is friendly and warm, we are doing

more than describing how he acted on a particular occasion. Instead, we are

describing the person and, with that, providing some expectations about how he

will act on other occasions, in other settings. But is this right? Is someone’s

behavior stable in this way?

HOW CONSISTENTARE PEOPLE ?

In

one classic study, researchers examined the behavior of schoolchildren—and, in

par-ticular, the likelihood that each child would be dishonest in one setting

or another (Hartshorne & May, 1928). Quite remarkably, the researchers

found little consistency in children’s behavior: Children who were inclined to

cheat on a school test were often quite honest in other settings (e.g., an

athletic contest), and vice versa. Based on these findings, it would be

misleading to describe these children with trait labels like “honest” or

“dishonest”—sometimes they were one, and sometimes the other.

Some

40 years ago, Walter Mischel reviewed this and related studies, and concluded

that people behave much less consistently than a trait conception would

predict, a state of affairs which has been referred to as the personality paradox (Mischel, 1968). Thus,

for example, the correlation between honesty measured in one setting and

honesty measured in another situation was .30, which Mischel argued was quite

low. Mischel noted that behaviors were similarly inconsistent for many other

traits, such as aggres-sion, dependency, rigidity, and reactions to authority.

Measures for any of these, taken in one situation, typically do not correlate

more than .30 with measures of the same traits taken in another situation.

Indeed, in some studies, there is no detectable corre-lation at all (Mischel,

1968; Nisbett, 1980). These findings led Mischel to conclude that trait

conceptions of personality dramatically overstate the real consistency of a

person’s behavior.

WHY AREN ’T PEOPLE MORE CONSISTENT ?

How

should we think about these results? One option is to argue that our

personalities are, in fact, relatively stable just as the trait approach

suggests, but acknowledge that situations often do shape our behavior. Given a

red light, most drivers stop; given a green light, most go—regardless of

whether they are friendly or unfriendly, stingy or generous, dominant or

submissive. Social roles likewise often define what people do independent of

their personalities. To predict how someone will act in a courtroom, for

example, there is little point in asking whether he is sociable, careless with

money, or good to his mother. What we really want to know is the role that he

will play—judge, prosecutor, defense attorney, or defendant.

We

reviewed studies indicating that the influence of a situation can be incredibly

powerful—leading ordinary college students to take on roles in which they are

vicious and hurtful to their peers. It’s no wonder, then, that there is

sometimes lit-tle correspondence between our traits and our behavior and less

consistency in our behavior than the trait perspective might imply. The reason,

in brief, lies in what’s called the power

of the situation. Because of that power, our behavior often depends more on

thesetting we are in than on who we are.

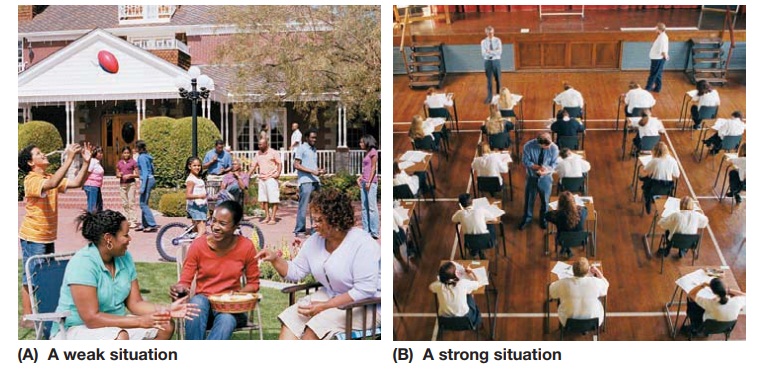

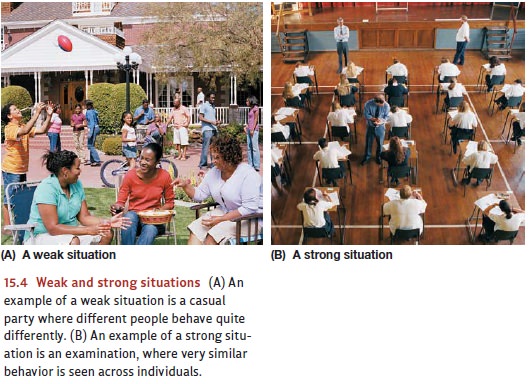

Sometimes,

though, our behavior does depend on

who we are. Particularly in weak situations—ones in which the environment

provides few guides for our behavior—our personalities shape our actions

(Figure 15.4). Even in strong situations—ones in which the environment provides

clear guides for our behavior—different people react to the situation in

somewhat different ways, so that their behavior in the end reflects the inter-action of the situation with their

personality (Fleeson, 2004; Magnusson & Endler,1977). Moreover, it’s not a

matter of chance how a particular person reacts to this situation or that one;

instead, people seem to be relatively consistent in how they act in certain types of situations. Thus, for example, someone

might be punctual in profes-sional settings, but regularly late for social

occasions; they might be shy in larger groups, but quite outgoing when they are

with just a few friends.

Evidence

for these points comes from many sources, including a study in which chil-dren

in a summer camp were observed in a variety of situations—settings, for

example, in which they were teased or provoked by a peer, or settings in which

they were approached in a friendly way by a peer, or settings in which they

were scolded by an adult (Cervone & Shoda, 1999; Mischel, Shoda, &

Mendoza-Denton, 2002). In this study, the researchers relied on behavioral data—data based on

observations of specific actions— and these data showed that each child’s

behavior varied from one situation to the next. For example, one child was not

at all aggressive when provoked by a friend, but responded aggressively when

scolded by an adult. Another child showed the reverse pat-tern. Thus, the trait

label aggressive would not

consistently fit either child—sometimes they were aggressive and sometimes they

were not.

There

was, however, a clear pattern to the children’s behavior, but the pattern

emerges only when we consider both the person and the situation. As the

investigators described it, the data suggested that each of the children had a

reliable “if . . . then . . .” profile: “If in this setting, then act in this

fashion; if in that setting, then act in that fashion” (Mischel et al., 2002).

Because of these “if . . . then . . .” patterns, the children were, in fact,

reason-ably consistent in how they acted, but their behaviors were “tuned” to

the situations they found themselves in. Thus, we need to be careful when we

describe any of these children as being “friendly” or “aggressive” or

“helpful,” relying only on global trait labels. To give an accurate

description, we need to be more specific, saying things like “tends to be

friendly in this sort of setting,” “tends to be helpful in that sort of

setting,” and so on.

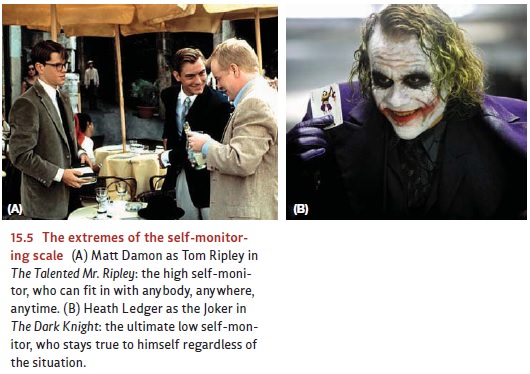

ARE SOME PEOPLE MORE INFLUENCED BY THE SITUATION THAN OTHERS ?

There

is one more complexity we must keep in mind as we consider how personality and

situations interact to shape behavior. Some individuals are more consistent

than others across situations, or, turning this around, some individuals are

more flexible than others. This difference among people is assessed by the Self-Monitoring Scale, developed by

Mark Snyder and designed to assess the degree to which people are sen-sitive to

their surroundings and likely to adjust their behaviors to fit in. The scale

includes items such as “In different situations and with different people, I

often act like very different persons.”

High

self-monitors care a great deal about how they appear to others, and so, at a

cocktail party, they are charming and sophisticated; in a street basketball

game, they “trash talk.” In contrast, low self-monitors are less interested in

how they appear to

others.

They are who they are regardless of the momentary situation, making their

behavior much more consistent across situations (Figure 15.5; Gangestad &

Snyder, 2000; M. Snyder, 1987, 1995). This suggests that the extent to which

situations deter-mine an individual’s behavior varies by person, with

situations being more important determinants of high self-monitors’ behavior

than of low self-monitors’ behavior.

How

consistent individuals are also varies at the cultural level of analysis.

Americans, for example, are relatively consistent in how they describe

themselves, no matter whether they happen at the time to be sitting alone, next

to an authority figure, or in a large group (Kanagawa, Cross, & Markus,

2001). By contrast, Japanese partici-pants’ self-descriptions varied

considerably across contexts, and they were far more self-critical when sitting

next to an authority figure than when they were by themselves. There also

cultural differences in how consistent individuals want to be. In one study, researchers asked American and Polish

participants how they would respond to a request to take a survey about

beverage preferences. When asked to imagine they had previously agreed to such

requests, American participants said they would again agree to the

request—apparently putting a high value on self-consistency. Polish

partici-pants, by contrast, were much less concerned with self-consistency, and

so were less influenced by imagining that they had agreed to similar requests

in the past (Cialdini, Wosinka, Barrett, Butner, & Gornik-Durose, 1999).

Related Topics