Chapter: Psychology: Personality

Psychodynamic Approach: Psychoanalysis: Theory and Practice

Psychoanalysis: Theory and Practice

The

founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud (1856–1939; Figure 15.12), was a physi-cian

by training. After a stint as a medical researcher, though, financial pressures

led Freud to open a neurology practice in which he found that many of his

patients were suffering from a disorder then called hysteria (now called conversion

disorder). The symptoms of hysteria presented a helter-skelter catalog of

physical and mental com-plaints—total or partial blindness or deafness,

paralysis or anesthesia of various parts of the body, uncontrollable trembling

or convulsive attacks, and gaps in memory. Was there any underlying cause that

could make sense of this confusing array of symptoms?

FROM HYPNOSIS TO THE TALKING CURE

Freud

suspected that the hysterical symptoms were psychogenic symptoms—the results of some unknown psychological

cause—rather than the product of organic damage to the nervous system. His

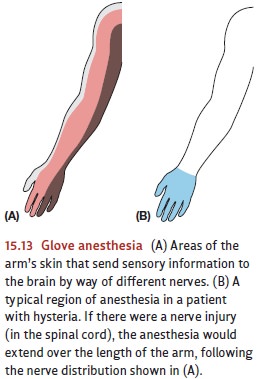

hypothesis grew out of the work of Jean Charcot (1825–1893), a French

neurologist who noticed that many of the bodily symptoms of hysteria made no

anatomical sense. For example, some patients who suffered from anesthesia

(i.e., lack of feeling) of the hand still had feeling above the wrist. This gloveanesthesia (so called because of

the shape of the affected region) could not possibly becaused by any nerve

injury, since an injury to any of the relevant nerve trunks would also affect a

portion of the arm above the wrist (Figure 15.13). This ruled out a simple

physical cause and suggested that glove anesthesia had some psychological

basis.

In

collaboration with another physician, Josef Breuer (1842–1925), Freud came to

believe that these hysterical symptoms were a disguised way to keep certain

emotionally charged memories under mental lock and key (S. Freud & Breuer,

1895). The idea, in brief, was that the patients carried some very troubling

memory that they needed to express (because it held such a grip on their

thoughts) but also to hide (because thinking about it was so painful). The

patients’ “compromise,” in Freud’s view, was to express the memory in a veiled

form, and this was the source of their physical symptoms.

To

support this hypothesis, Freud needed to find out both what a patient’s painful

memory was and why she (almost all of Freud’s patients were women) found

directly expressing her memory to be unacceptable. At first, Freud and Breuer

tried to uncover these memories while the patients were in a hypnotic trance.

Eventually, though, Freud abandoned this method, and came to the view that

crucial memories could instead be recovered in the normal, waking state through

the method of free association. In

this method, his patients were told to say anything that entered their mind, no

matter how trivial it seemed, or how embarrassing or disagreeable. Since Freud

assumed that all ideas were linked by association, he believed that the

emotionally charged “forgotten” memories would be mentioned sooner or later.

But

a difficulty arose: Patients did not readily comply with Freud’s request.

Instead, they avoided certain topics and carefully tuned what they said about

others, showing resistance that the patients themselves were often unaware of.

In Freud’s view, this resist-ance arose because target memories (and related

acts, impulses, or thoughts) were espe-cially painful or anxiety-provoking.

Years before, as an act of self-protection, the patients had pushed these

experiences out of consciousness, or, in Freud’s term, they had repressed the memories. The same

self-protection was operating in free association,keeping the memories from the

patients’ (or Freud’s) view. On this basis, Freud con-cluded that his patients

would not, and perhaps could not, reveal their painful memories directly. He

therefore set himself the task of developing indirect methods of analysis—as he called it, psychoanalysis—that he thought would uncover these ideas and

memories and the conflicts that gave rise to them.

ID,

EGO, AND SUPEREGO

Much

of Freud’s work, therefore, was aimed at uncovering his patients’ unconscious

con-flicts. He was convinced that these conflicts were at the root of their

various symptoms, and that, by revealing the conflicts, he could diminish the

symptoms. But Freud also believed that the same conflicts and mechanisms for

dealing with them arise in normal persons, so he viewed his proposals as

contributions not only to psychopathology but also to a general theory of

personality.

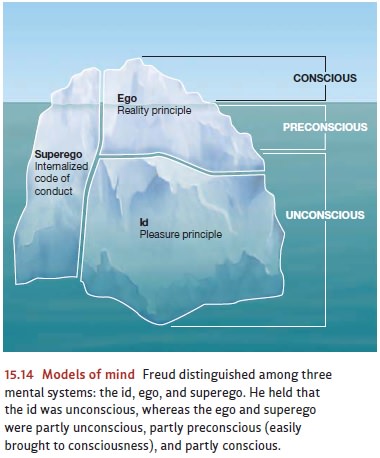

But

what sorts of conflict are we considering here? What are the warring factions,

supposedly hidden deep inside each individual? According to Freud, the

conflicts ham-pering each of us involve incompatible wishes and motives, such

as a patient’s desire to go out with friends versus her guilt over leaving a

sick father at home. Freud devised a conception of personality that

encapsulated these conflicting forces within three dis-tinct subsystems: the id, the ego, and the superego

(Figure 15.14). In some of his writings, Freud treated these three mental

systems as if they were separate persons inhabiting the mind. But this is only

a metaphor that must not be taken literally; id, ego, and superego are just the

names he gave to three sets of very different reaction patterns, and not

persons in their own right (S. Freud, 1923).

The

id is the most primitive portion of

the personality, the portion from which the other two emerge. It consists of

all of the basic biological urges, and seeks constantly to reduce the tensions

generated by these biological urges. The id abides entirely by the pleasure principle—satisfaction now and

not later, regardless of the circumstances andwhatever the cost.

At birth, the infant’s mind is all id. But the id’s heated striving is soon met by cold reality, because some gratifications take time. Food and drink, for example, are not always present; the infant or young child has to cry to get them. Over the course of early childhood, these confrontations between desire and reality lead to a whole set of new reactions that are meant to reconcile the two. Sometimes the result is appropriate action (e.g., saying “please”), and sometimes the result is suppressing a forbidden impulse (e.g., not eating food from someone else’s plate). In all cases, though, these efforts at reconciling desire and reality become organized into a new subsystem of the personality—the ego. The ego obeys a new principle, the reality principle. It tries to sat-isfy the id (i.e., to gain pleasure), but it does so pragmatically, finding strategies that work but also accord with the demands of the real world.

If,

for a very young child, the ego inhibits some id-inspired action, it is for an

imme-diate reason. Early in the child’s life, the reason is likely to be some

physical obstacle (perhaps the food is present, but out of reach). For a

slightly older child, the reason may be social. Grabbing the food from your

brother will result in punishment by a nearby parent. As the child gets older

still, though, a new factor enters the scene. Imagine that the child sees a

piece of candy within reach but knows that eating the candy is forbid-den. By

age 5 or so, the child may overrule the desire to eat the candy even when there

is no one around and so no chance of being caught and punished. This inhibition

of the desired action occurs because the child has now internalized the rules

and admoni-tions of the parents and so administers praise or scolding to

himself, in a fashion appropriate to his actions. At this point, the child has

developed a third aspect to his personality: a superego, an internalized code of conduct. If the ego lives up to

the superego’s dictates, the child is rewarded with feelings of pride. But if

one of the super-ego’s rules is broken, the superego metes out

punishment—feelings of guilt or shame.

Related Topics