Chapter: Pharmaceutical Biotechnology: Fundamentals and Applications : Formulation of Biotech Products, Including Biopharmaceutical Considerations

Potential Pitfalls in Tumor Targeting

Potential Pitfalls in Tumor Targeting

Upon IV injection, only a small fraction of the homing

device–carrier–drug complex is sequestered at the target site. Apart from the

compartmentalization of the body (see above: anatomical and physiological

hurdles) and consequently the carrier-dependent barriers that result, several

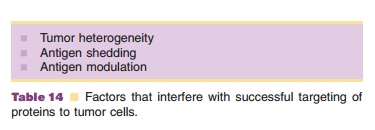

other factors account for this lack of target site accumulation (Table 14).

How successful are MAb in discriminating target cells (tumor cells) from

non-target cells? Do all tumor cells expose the tumor-associated antigen? These

questions are still difficult to answer (Hellstro¨m et al., 1987). Tumor

cell-surface specific molecules used for homing purposes are often

differentiation antigens on the tumor cell wall. These structures are not

unique since they occur in a lower density level on non-target cells as well.

Therefore, the target site specificity of MAb raised against these structures

is more quantitative than qualitative in nature.

Another category of tumor-associated antigens are the clone-specific

antigens. They are unique for the clone forming the tumor. However, the

practical problem when focusing on clone-specific antibodies for drug targeting

is that each patient probably needs a tailor-made MAb.

The surface “make-up” of tumor cells in a tumor or a metastasis is not

constant; neither in time nor between cells in the same tumor. There are many

subpopulations of tumor cells and they express different surface molecules.

This heterogeneity means that not all cells in the tumor will interact with

one, single targeted conjugate. Antigen shedding and antigen modulation are two

other ways tumor cells can avoid recognition. Shedding of antigens means that

antigens are released from the surface. They can then interact with circulating

conjugates outside the target area, form an antigen–antibody complex and neutralize

the homing potential of the conjugates before the target area has been reached.

Finally, antigen modulation can occur upon binding of MAb to the cell surface

antigen. Modulation is the phenomenon that upon endocytosis of the (originally

exposed) surface antigen–immunoconjugate complex, some of these antigens are

not exposed anymore on the surface; there is no replenishment of endocytosed

surface antigens.

Four strategies can be implemented to solve problems related to tumor

cell heterogeneity, shed-ding and modulation. (i)

Cocktails of different MAb attached to the toxin can be used. (ii) Another approach is to give up striving for complete target cell

specificity and to induce so-called “bystander” effects. Then, the targeted

system is designed in such a way that the active part is released from the

conjugate after reaching a target cell, but before the antigen-conjugate

complex has been taken up (is endocytosed) by the target cell. (iii) Not all surface antigens show shedding or modulation. If these phenomena

occur, other antigen/MAb combinations should be selected that do not

demonstrate these effects. (iv) At the present, injection of

free MAb prior to injection of the immunoconjugate is under inves-tigation to

neutralize “free” circulating antigen; then, the subsequently injected

conjugate should not encounter shedded, free antigen.

In conclusion, targeted (modified) MAb and MAb-conjugates are now

studied to assess their value in fighting life-threatening diseases such as

cancer. During the last decade, technology has evolved quickly; many different

new options became avail-able. Lack of detailed pathophysiological and cell

biological knowledge about the behavior of tumors, for instance, slows down

progress. It is even possible that the whole concept of MAb-(conjugates) will

turn out to be only of limited therapeutic value, because ofproblems such as

tumor cell heterogeneity, poor access to tumors and immunogenicity concerns.

Related Topics