Chapter: Human Nervous System and Sensory Organs : Functional Systems

Brain Function

Brain Function

The

central nervous system enables the organism to adapt to the environment and to

survive. It receives stimuli from outside and inside the body through the

sensory organs; it then filters the stimuli and processes them into

information. In accordance with this information, it sends impulses to the

periphery of the body so that the organism can react in a meaningful way to the

con-stantly changing conditions. The functional systems described in this

chapter are by no means independent, isolated sys-tems. The highly simplified

and schematic description is supposed to provide an ap-proximate illustration

of the extremely complex interactions among billions of nerve cells.

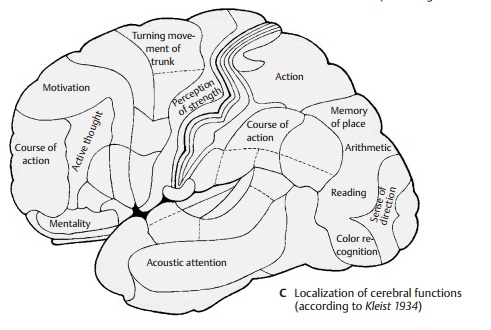

For

centuries there has been the simple mechanistic idea that sensations reach the

brain and the brain then triggers motor re-actions. According to Descartes, optic stimuli are

transmitted from the eyes to the pineal gland (epiphysis), which then sends

im-pulses that travel to the muscles (A).

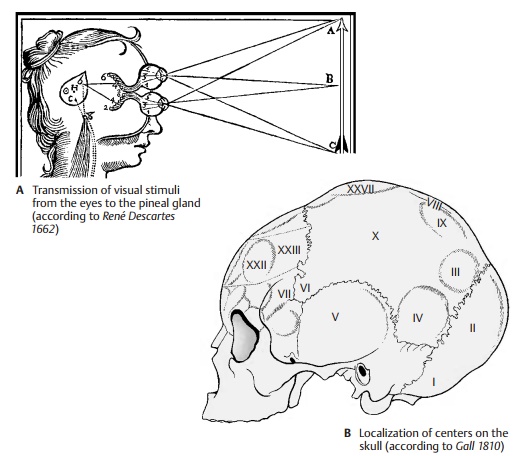

He viewed the pineal gland as the seat of the soul. Franz Gall was the first to postulate the importance of the

cerebral convolutions and the cerebral cortex for brain function. He localized

the “organs of the soul” on the surface of the hemispheres, and he believed

that mental faculties could be determined to various degrees by the

topographical fea-tures on the surface of the skull (phrenology) (B). He used

Roman numerals for localizing these features: I, reproductive instinct; II,

love of offspring; III, friendship; IV, bravery; V, instinct to eat meat; VI,

intelligence; VII, greed and cleptomania; VIII, pride and arrogance; IX,

vanity and ambition; and so on.

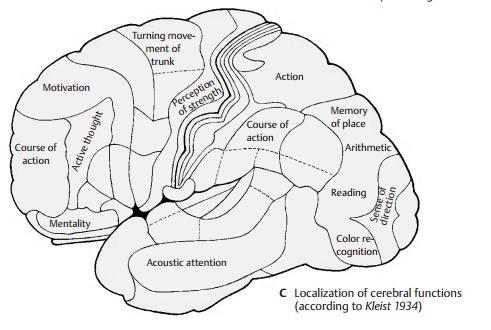

On the

basis of brain injuries, Kleist

arrived at localizations of higher cerebral functions (C). He assumed that positive capacities, or “functions,” would

correspond to deficits in recognition and thinking, motivation and action,

among others, which were ex-pressed as negative pathological findings. However,

this is not so. While it is possibleto localize symptoms of deficit, this

cannot be done for capacities (von Monakow). Crit-ics of this theory of localization and centers spoke

of “brain mythology.” Ultimately, specific capacities cannot be attributed to

specific brain regions because immense numbers of other neuronal groups are

al-ways participating in the stimulation, inhi-bition, or modulation of a

capacity. The so-called “centers” can be regarded, at best, as important relay stations for a particular

capacity. Nor is the central nervous system a rigid apparatus; rather it

exhibits a con-siderable degree of plasticity.

Especially in the infant brain, other centers can take over and perform

functions in place of injured parts of the brain. Plasticity of our principal

organ is also a prerequisite for the capacity to learn (language, writing,

physical skills).

Information

processing in the telencephalon is known as integration. It refers to the combination and interconnection of

sensations, including stored experience, to form a higher and complex

functional unit. In this way, the functions of the organism are guided by means

of the meticulous mutual coordination between groups of neurons. During human

evolution, the inte-grative processes of regulating and coordi-nating

elementary biological tasks have developed into conscious recognition, thought,

and action. Cybernetics and com-puter technology have provided us with models

for the function of the brain (cogni-tive science). According to these models,

various “functions” are based on the con-tinuously changing stimuli within

intercon-nected neuronal circuits.

Despite

our highly developed instrument technology, there is ultimately only one

in-strument available for brain research: the brain itself. In other words, a

human organ is involved in an attempt to investigate its own structure and

function.

Related Topics