Chapter: Psychology: Personality

Psychodynamic Approach: The Empirical Basis of FreudŌĆÖs Claims

The Empirical Basis of FreudŌĆÖs Claims

Many

people regard FreudŌĆÖs claimsŌĆöespecially his account of the Electra complexŌĆöas

incredibly far-fetched, but Freud believed firmly that his conception was

demanded by the evidence he collected. In the next section, we first consider

why Freud believed his claims were justified. Then, in the following section,

we consider contemporary criticisms of FreudŌĆÖs methods and inferences.

THE NATURE OF FREUD ŌĆÖSEVIDENCE

As

we have seen, Freud believed that painful beliefs and ideas were repressed, but

that the repression was never complete. Therefore, these anxiety-producing

ideas would still come to the surfaceŌĆöbut (thanks to other defense mechanisms)

only in disguised form. The evidence for FreudŌĆÖs theory therefore had to come

from a process of interpre-tation that allowed Freud to penetrate the disguise

and thus to reveal the crucial under-lying psychological dynamics.

As

one category of evidence, Freud continually drew attention to what he called

the ŌĆ£psychopathology of everyday life.ŌĆØ For example, we might forget a name or

suffer a slip of the tongue, and, for Freud, these incidents were important

clues to the personŌĆÖs hidden thoughts: Perhaps the name reminded us of an

embarrassing moment, and perhaps the slip of the tongue allowed us to say

some-thing that we wanted to say, but knew we shouldnŌĆÖt (Figure 15.16). Freud

argued that in some cases these slips were revealing, and, if properly

interpreted in the context of other evidence, they could pro-vide important

insights into an individualŌĆÖs unconscious thoughts and fears.

Freud

also believed that we could learn much about an individual through the

interpretation of dreams (S. Freud, 1900), because, in FreudŌĆÖs view, all dreams

are attempts at wish fulfillment. While one is awake, a wish is usually not

acted on right away, for there are con-siderations of both reality (the ego)

and morality (the superego) that must be taken into account: Is it possible? Is

it allowed? But during sleep these restraining forces are drastically weakened,

and the wish then leads to immediate thoughts and images of gratification. In

some cases the wish fulfillment is simple and direct. Starving explor- ers

dream of sumptuous meals; people stranded in the desert dream of cool mountain

streams. According to a Hungarian proverb quoted by Freud, ŌĆ£Pigs dream of

acorns, and geese dream of maize.ŌĆØ

What

about our more fantastic dreams, the ones with illogical plots, bizarre

charac-ters, and opaque symbolism? These are also attempts at wish fulfillment,

Freud believed, but with a key difference. They touch on forbidden,

anxiety-laden ideas that cannot be entertained directly. As a result, various

mechanisms of defense prohibit the literal expression of the idea but allow it

to slip through in disguised, symbolic form (e.g., a penis may be symbolized as

a sword, a vagina as a cave). Because of this disguise, the dreamer may never

experience the underlying latent content

of the dreamŌĆöthe actual wishes and concerns that the dream is constructed to

express. What he experiences instead is the carefully laundered version that

emerges after the defense mechanisms have done their workŌĆöthe dreamŌĆÖs manifest content. This self-protection

takes mental effort, but, according to Freud, the alternativeŌĆöfacing our

impulses unadulteratedŌĆö would let very few of us sleep for long.

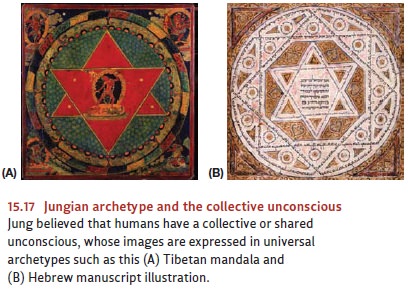

Yet

another form of evidence that Freud pointed to are the myths, legends, and

fairy tales shared within a culture. He contended that just as dreams are a

window into the individualŌĆÖs unconscious, these (often unwritten) forms of

literature allow us a glimpse into the hidden concerns shared by whole cultural

groups, if not all of humanity. Indeed, one of FreudŌĆÖs earliest colleagues, the

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung (1875ŌĆō1961), argued for a collective unconscious consisting of primordial sto-ries and

imagesŌĆöhe called these archetypesŌĆöthat

shape our perceptions and desires just as much as FreudŌĆÖs psychodynamics (Jung,

1964; Figure 15.17). Psychoanalysts

who

have delved into such tales have found, for example, an ample supply of Oedipal

themes. There are numerous ogres, dragons, and monsters to be slain before the

prize can be won. The villain is often a cruel stepparentŌĆöa fairly transparent

symbol, in their view, of Oedipal hostilities (see Figure 15.18).

CONCERNS ABOUT PSYCHODYNAMIC EVIDENCE

As

we have just seen, FreudŌĆÖs evidence generally involved his patientsŌĆÖ symptoms,

actions, slips of the tongue, dreams, and so on. Freud was convinced, however,

that these observations should not be taken at face value; instead, they needed

to be inter-preted, in order to

unmask the underlying dynamic that was being expressed. The difficulty,

though, is that Freud allowed himself many options for this interpretationŌĆöand

so, if someone said ŌĆ£I hate my father,ŌĆØ that might mean (via the defense of

projection) that the person is convinced her father hates her or it might mean

(via displacement) that the person hates her mother, or it might mean something

else altogether. With this much flexibility, one might fear, there is no way to

discover the correct interpretation of this utterance, and so no way to be

certain our overall account is accurate. Indeed, it is telling that some of

FreudŌĆÖs followers were able to draw very different conclusions from the same

clinical cases that Freud himself studiedŌĆöa powerful indi-cator that the

interpretations Freud offered were in no sense demanded by the evidence.

When we turn to more objective forms of evidence we often find facts that do not fit well with Freudian theory. For example, one of the cornerstones of psychoanalytic thought is repression. Yet results of empirical studies of repression have been mixed. Some results point in the same direction as FreudŌĆÖs claims about repression (M. C. Anderson et al., 2004; M. C. Anderson & Levy, 2006; Joslyn & Oakes, 2005), but other research yields no evidence for the mechanisms Freud proposed (Holmes, 1990), and at least some of the studies that allegedly show repression have been roundly criticized by other researchers (Kihlstrom, 2002).

Related Topics