Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Dermatologic Problems

Wound Care for Skin Conditions

Wound Care for Skin Conditions

There

are three major classifications of dressings for skin condi-tions: wet,

moisture-retentive, and occlusive. During the 1980s and 1990s, new product

development quadrupled the available choices for wound care, especially within

the moisture-retentive dressing classification. Products classified as

moisture-retentive dressings include hydrogels, foams, and alginates.

Biologicals and biosynthetics containing collagen and growth factor are being

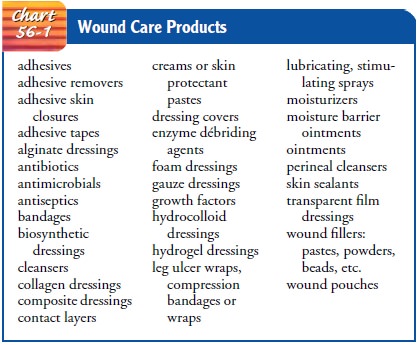

researched and will soon be available. Chart 56-1 lists generic wound care

products. Consultation with a wound care specialist can be very helpful in

choosing the product most appropriate for the patient.

Dressings and Rules of Wound Care

Even

with the increased availability of dressings, an appropriate selection can be

made if certain principles are maintained, re-ferred to as the five rules of

wound care (Krastner, et al, 2002).

Rule 1: Categorization.

The nurse should learn about dressingsby generic category and compare new

products with those that already make up the category. As hundreds of choices

become available, the nurse should become familiar with the generic cat-egories

and develop a systematic approach to product selection. The nurse should become

familiar with indications, contra-indications, and side effects. The best

dressing may be created by combining products in different categories to

achieve several goals at the same time. These categories are discussed in sub-sequent

sections.

Rule 2: Selection.

The nurse should select the safest and mosteffective, user-friendly, and cost-effective dressing possible. In many cases, nurses carry out the physician’s prescriptions for dressings, but they should be prepared to give the physician feed-back about the dressing’s effect on the wound, ease of use for the patient, and other considerations when applicable.

Rule 3: Change.

The nurse changes dressings based on patient,

wound, and dressing assessments, not on standardized routines. Traditional

nursing care plans recommended changing dressings on a routine schedule, often

three or four times each day.

Rule 4: Evolution.

As the wound progresses through the phasesof wound healing, the dressing

protocol is altered to optimize wound healing. It is rare, especially in cases

of chronic wounds, that the same dressing material is appropriate throughout

the healing process. The rule assumes that the nurse and the patient or family

have access to a wide variety of products and knowledge about their use. The

nurse teaches the patient or family caregiver about wound care and ensures that

the family has access to ap-propriate dressing choices.

Rule 5: Practice.

Practice with dressing material is required forthe nurse to learn the

performance parameters of the particular dressing. Refining the skills of

applying appropriate dressings cor-rectly and learning about new dressing

products are essential nursing responsibilities. Dressing changes should not be

dele-gated to assistive personnel; these techniques require the knowl-edge base

and assessment skills of professional nurses.

Wet Dressings

Wet dressings (ie, wet compresses applied to the

skin) were tra-ditionally used for acute, weeping, inflammatory lesions. They

have become almost obsolete in light of the many newer products available for

wound care. Wet dressings are sterile or nonsterile (clean), depending on the

skin disorder. They are used to reduce inflammation by producing constriction

of the blood vessels (thereby decreasing vasodilation and local blood flow in

inflam-mation); to clean the skin of exudates, crusts, and scales; to main-tain

drainage of infected areas; and to promote healing by facilitating the free

movement of epidermal cells across the in-volved skin so that new granulation

tissue forms. Wet dressings can be used for vesicular, bullous, pustular, and

ulcerative disor-ders, as well as for inflammatory conditions.

Before applying these dressings, the nurse performs

hand hy-giene and puts on sterile or clean gloves. The open dressing requires

frequent changes because evaporation is rapid. The closed dress-ing is changed

less frequently, but there is always a danger that the closed dressing may

cause not only softening and but actual maceration of the underlying skin.

Wet-to-dry dressings are used to remove exudate from erosions or ulcers. The

dressing remains in place until it dries. It is then removed without soaking so

that crusts, exudate, or pus from the skin lesion adhere to the dressing and are

removed with it.

Moisture-Retentive Dressings

Newer, commercially produced moisture-retentive

dressings can perform the same functions as wet compresses but are more

effi-cient at removing exudate because of their higher moisture-vapor

transmission rate; some have reservoirs that can hold excessive ex-udate. There

is also evidence that moist wound healing results in wound resurfacing 40%

faster than with air exposure. A number of moisture-retentive dressings are

already impregnated with saline solution, petrolatum, zinc-saline solution,

hydrogel, or anti-microbial agents, thereby eliminating the need to coat the

skin to avoid maceration. The main advantages of moisture-retentive dressings

over wet compresses are reduced pain, fewer infections, less scar tissue,

gentle autolytic débridement, and decreased fre-quency of dressing changes.

Depending on the product used and the type of dermatologic problem encountered,

most moisture-retentive dressings may remain in place from 12 to 24 hours; some

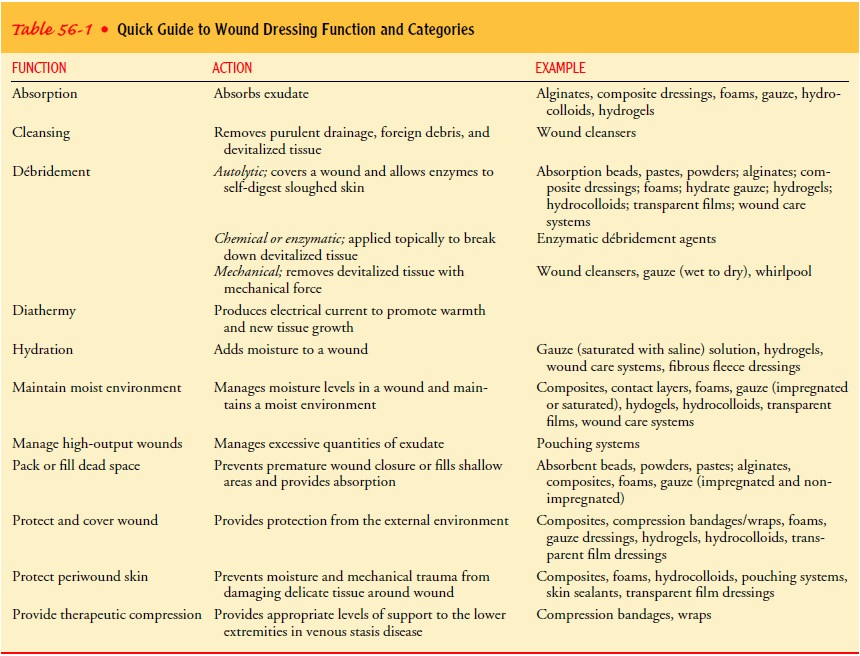

can remain in place as long as a week. Table 56-1 is a guide to wound dressing

functions and categories.

Hydrogels are polymers with a 90% to 95% water

content. They are available in impregnated sheets or as gel in a tube. Their

high moisture content makes them ideal for autolytic débride-ment of wounds.

They are semitransparent, allowing for wound inspection without dressing

removal. They are comfortable and soothing for the painful wound. They have no

inherent adhesive and require a secondary dressing to keep them in place.

Hydro-gels are appropriate for superficial wounds with high serous out-put,

such as abrasions, skin graft sites, and draining venous ulcers.

Hydrocolloids are composed of a water-impermeable,

poly-urethane outer covering separated from the wound by a hydro-colloid

material. They are adherent and nonpermeable to water vapor and oxygen. As it

evaporates over the wound, water is ab-sorbed into the dressing, which softens

and discolors with the increased water content. The dressing can be removed without

damage to the wound. As the dressing absorbs water, it produces a

foul-smelling, yellowish covering over the wound. This is a normal chemical

interaction between the dressing and wound exudate and should not be confused

with purulent drainage from the wound. Unfortunately, most of the hydrocolloid

dressings are opaque, lim-iting inspection of the wound without removal of the

dressing.

Available in sheets and in gels, hydrocolloids are a good choice for exudative wounds and for acute wounds. Easy to use and comfortable, hydrocolloid dressings promote débridement and formation of granulation tissue. They do not have to be removed for bathing. Most can be left in place for up to 7 days.

Foam

dressings consist of microporous polyurethane with an absorptive hydrophilic (ie, water-absorbing)

surface that covers the wound and a hydrophobic

(ie, water-resistant) backing to block leakage of exudate. They are nonadherent

and require a secondary dressing to keep them in place. Moisture is absorbed

into the foam layer, decreasing maceration of surrounding tis-sue. A moist

environment is maintained, and removal of the dressing does not damage the

wound. The foams are opaque and must be removed for wound inspection. Foams are

a good choice for exudative wounds. They are especially helpful over bony

prominences because they provide contoured cushioning.

Calcium

alginates are derived from seaweed and consist of tremendously absorbent

calcium alginate fibers. They are hemo-static and bioabsorbable and can be used

as sheets, mats, or ropes of absorbent material. As the exudate is absorbed,

the fibers turn into a viscous hydrogel. They are quite useful in areas where

the tissue is more irritated or macerated. The alginate dressing forms a moist

pocket over the wound while the sur-rounding skin stays dry. They also react

with wound fluid to form a foul-smelling coating. Alginates work well when

packed into a deep cavity, wound, or sinus tract with heavy drainage (Krastner

et al, 2002). They are nonadherent and require a secondary dressing.

Occlusive Dressings

Occlusive dressings may be commercially produced or

made in-expensively from sterile or nonsterile gauze squares or wrap. Occlusive

dressings cover topical medication that is applied to a dermatosis (ie, abnormal skin lesion). The area is kept airtightby

using plastic film (eg, plastic wrap). Plastic film is thin and readily adapts

to all sizes, body shapes, and skin surfaces. Plastic surgical tape containing

a corticosteroid in the adhesive layer can be cut to size and applied to

individual lesions. Generally, plastic wrap should be used no more than 12

hours each day.

AUTOLYTIC DÉBRIDEMENT

Autolytic débridement

is a process that uses the body’s own digestive enzymes to break down necrotic

tissue. The wound is kept moist with occlusive dressings. Eschar and necrotic

debris are softened, liquefied, and separated from the bed of the wound.

Several commercially available products contain the

same en-zymes that the body produces naturally. These are called enzy-matic

débriding agents; examples include Accu Zyme, collagenase (Santyl), Granulex,

and Zymase. Application of these products speeds the rate at which necrotic

tissue is removed. This method is still slower and no more effective than

surgical débridement. When enzymatic débridment is being used under an

occlusivedressing, a foul odor is produced by the breakdown of

cellular de-bris. This odor does not indicate that the wound is infected. The

nurse should expect this reaction, and help the patient under-stand the reason

for the odor.

Advances in Wound Treatment

Increasing understanding of how skin heals has led

to several ad-vances in therapy. Growth factors are cytokines or proteins that

have potent mitogenic activity (Valencia et al., 2001). Low levels of cytokines

circulate in the blood continuously, but activated platelets release increased

amounts of preformed growth factors into a wound. This increase in cytokines in

the wound stimulates cellular growth and granulation of skin. Regranex gel

contains be-caplermin, a platelet-derived growth factor, which is applied to

the wound to stimulate healing. Apligraf is a skin construct (ie,

bio-engineered skin substitute) imbedded in a dressing that also con-tains

cytokines and fibroblasts. When applied to wounds, these agents stimulate

platelet activity and potentially decrease wound healing time (Paquette &

Falanga, 2002).

Some oral medications are being investigated for

their bene-fits in healing chronic venous ulcers of the lower legs. Pentoxi-fylline

(Trental) increases peripheral blood flow by decreasing the viscosity of blood.

It has some fibrinolytic action and decreases leukocyte adhesion to the wall of

the blood vessels. Enteric-coated aspirin has also been shown to be of value,

although its exact mechanism is still not clear (Valencia et al., 2001).

Medical Management

THERAPEUTIC BATHS (BALNEOTHERAPY)AND MEDICATIONS

Baths

or soaks, known as balneotherapy,

are useful when large areas of skin are affected. The baths remove crusts,

scales, and old medications and relieve the inflammation and itching that

ac-company acute dermatoses. The water temperature should be comfortable, and

the bath should not exceed 20 to 30 minutes because of the tendency of baths

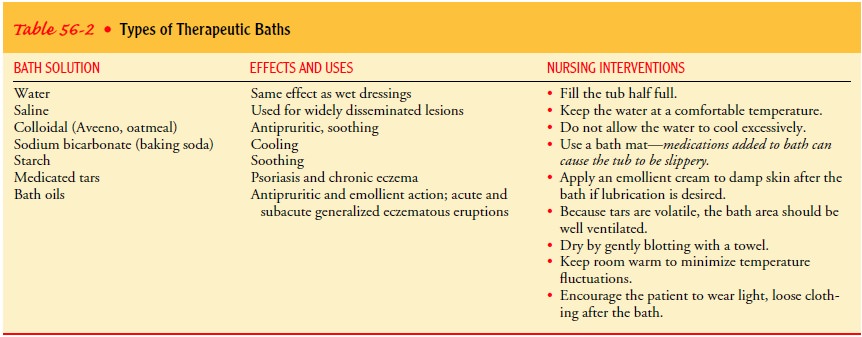

and soaks to produce skin mac-eration. Table 56-2 lists the different types of

therapeutic baths and their uses.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Because skin is easily accessible and therefore

easy to treat, topi-cal medications are often used. High concentrations of some

medications can be applied directly to the affected site with little systemic

absorption and therefore with few systemic side effects. However, some

medications are readily absorbed through the skin and can produce systemic

effects. Because topical prepara-tions may induce allergic contact dermatitis (ie, inflammation of the

skin) in sensitive patients, any untoward response should be reported

immediately and the medication discontinued.

Medicated lotions, creams, ointments, and powders

are fre-quently used to treat skin lesions. In general, moisture-retentive

dressings, with or without medication, are used in the acute stage; lotions and

creams are reserved for the subacute stage; and oint-ments are used when

inflammation has become chronic and the skin is dry with scaling or lichenification (ie, leathery

thickening).

With

all types of topical medication, the patient is taught to apply the medication

gently but thoroughly and, when neces-sary, to cover the medication with a

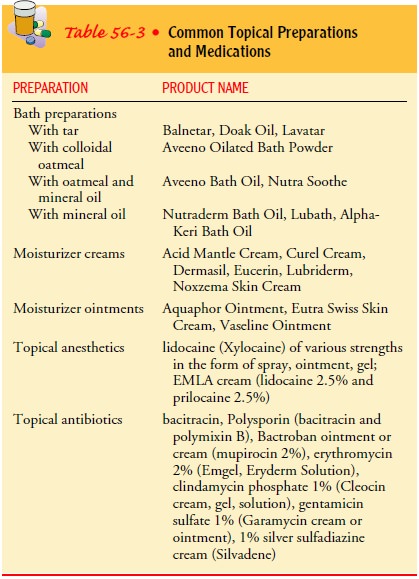

dressing to protect clothing. Table 56-3 lists some commonly used topical

preparations.

Lotions.

Lotions are of two types: suspensions and

liniments. Sus-pensions consist of a powder in water, requiring shaking before

application, and clear solutions, containing completely dissolved active

ingredients. Lotions are usually applied directly to the skin, but a dressing

soaked in the lotion can be placed on the affected area. A suspension such as

calamine lotion provides a rapid cool-ing and drying effect as it evaporates,

leaving a thin, medicinal layer of powder on the affected skin. Lotions are

frequently used to replenish lost skin oils or to relieve pruritus. Lotions

must be applied every 3 or 4 hours for sustained therapeutic effect. If left in

place for a longer period, they may crust and cake on the skin. Liniments are

lotions with oil added to prevent crusting. Because lotions are easy to use,

therapeutic compliance is generally high.

Powders.

Powders usually have a talc, zinc oxide, bentonite, orcornstarch base and are dusted on the skin with a shaker or with cotton sponges. Although their therapeutic action is brief, pow-ders act as hygroscopic agents that absorb and retain moisture from the air and reduce friction between skin surfaces and cloth-ing or bedding.

Creams.

Creams may be suspensions of oil in water or

emulsions of water in oil, with additional ingredients to prevent bacterial and

fungal growth. Both may cause an allergic reaction such as contact dermatitis.

Oil-in-water creams are easily applied and usually are the most cosmetically

acceptable to the patient. Although they can be used on the face, they tend to

have a drying effect. Water-in-oil emulsions are greasier and are preferred for

drying and flaking dermatoses. Creams usually are rubbed into the skin by hand.

They are used for their moisturizing and emollient effects.

Gels.

Gels are semisolid emulsions that become liquid when

ap-plied to the skin or scalp. They are cosmetically acceptable to the patient

because they are not visible after application, and they are greaseless and

nonstaining. The newer water-based gels appear to penetrate the skin more

effectively and cause less stinging on ap-plication. They are especially useful

for acute dermatitis in which there is weeping exudate (eg, poison ivy).

Pastes.

Pastes are mixtures of powders and ointments and areused in inflammatory

blistering conditions. They adhere to the skin and may be difficult to remove

without using an oil (eg, olive oil, mineral oil). Pastes are applied with a

wooden tongue depressor or gloved hand.

Ointments.

Ointments retard water loss and lubricate and pro-tect the skin. They are

the preferred vehicle for delivering med-ication to chronic or localized dry

skin conditions, such as eczema or psoriasis. Ointments are applied with a

wooden tongue de-pressor or by hand (gloved).

Sprays and Aerosols.

Spray and aerosol preparations may beused on any widespread dermatologic

condition. They evaporate on contact and are used infrequently.

Corticosteroids.

Corticosteroids are widely used in treating

der-matologic conditions to provide anti-inflammatory, antipruritic, and

vasoconstrictive effects. The patient is taught to apply this medication

according to strict guidelines, using it sparingly but rubbing it into the

prescribed area thoroughly. Absorption of top-ical corticosteroid is enhanced

when the skin is hydrated or the affected area is covered by an occlusive or

moisture-retentive dressing. Inappropriate use of topical corticosteroids can

result in local and systemic side effects, especially when the medication is

absorbed through inflamed and excoriated skin, under occlusive dressings, or

when used for long periods on sensitive areas. Local side effects may include

skin atrophy and thinning, striae (ie, band-like streaks), and telangiectasia.

Thinning of the skin results from the ability of corticosteroids to inhibit

skin collagen synthesis (Odom et al., 2000). The thinning process can be

reversed by discontinuing the medication, but striae and telangiectasia are

per-manent. Systemic side effects may include hyperglycemia and symptoms of

Cushing’s syndrome. Caution is required when ap-plying corticosteroids around

the eyes because long-term use may cause glaucoma or cataracts, and the

anti-inflammatory effect of corticosteroids may mask existing viral or fungal

infections.

Concentrated

(fluorinated) corticosteroids are never applied on the face or intertriginous

areas (ie, axilla and groin), because these areas have a thinner stratum

corneum and absorb the med-ication much more quickly than areas such as the

forearm or legs. Persistent use of concentrated topical corticosteroids in any

loca-tion may produce acnelike dermatitis, known as steroid-induced acne, and

hypertrichosis (ie, excessive hair growth). Because some topical corticosteroid

preparations are available without pre-scription, patients should be cautioned

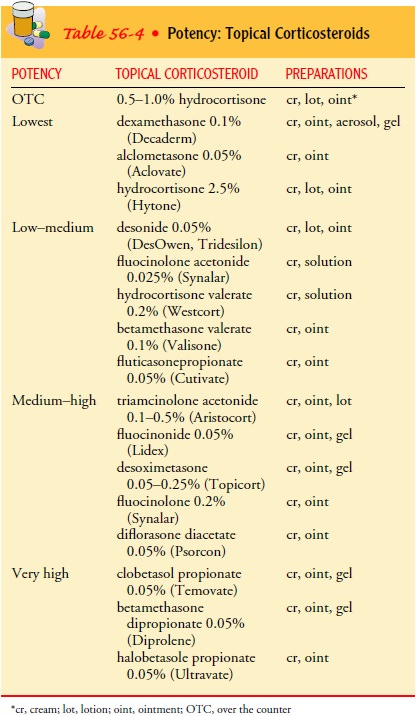

about prolonged and in-appropriate use. Table 56-4 lists topical corticosteroid

preparations according to potency.

Intralesional Therapy.

Intralesional therapy consists of injectinga sterile suspension of

medication (usually a corticosteroid) into or just below a lesion. Although

this treatment may have an anti-inflammatory effect, local atrophy may result

if the medication is injected into subcutaneous fat. Skin lesions treated with

in-tralesional therapy include psoriasis, keloids, and cystic acne.

Occasionally, immunotherapeutic and antifungal agents are ad-ministered as

intralesional therapy.

Systemic Medications.

Systemic medications are also prescribed for skin

conditions. These include corticosteroids for short-term therapy for contact

dermatitis or for long-term treatment of a chronic dermatosis, such as

pemphigus vulgaris. Other frequently used systemic medications include

antibiotics, antifungals, anti-histamines, sedatives, tranquilizers,

analgesics, and cytotoxic agents.

Nursing Management

Management begins with a health history, direct observation, and a complete physical examination. Because of its visibility, a skin condition is usually difficult to ignore or conceal from others and may therefore cause the patient some emotional distress. The major goals for the patient may include maintenance of skin integrity, relief of discomfort, promotion of restful sleep, self-acceptance, knowledge about skin care, and avoidance of complications.

Nursing

management for patients who must perform self-care for skin problems, such as

applying medications and dressings, focuses mainly on teaching the patient how

to wash the affected area and pat it dry, apply medication to the lesion while

the skin is moist, cover the area with plastic (eg, Telfa pads, plastic wrap,

vinyl gloves, plastic bag) if recommended, and cover it with an elastic

bandage, dressing, or paper tape to seal the edges. Dressings that contain or

cover a topical corticosteroid should be removed for 12 of every 24 hours to

prevent skin thinning (ie, atrophy), striae, and telangiectasia (ie, small, red

lesions caused by dilation of blood vessels).

Other forms of dressings, such as those used to

cover topical medications, include soft cotton cloth and stretchable cotton

dress-ings (eg, Surgitube, TubeGauz) that can be used for fingers, toes, hands,

and feet. The hands can be covered with disposable poly-ethylene or vinyl gloves

sealed at the wrists; the feet can be wrapped in plastic bags covered by cotton

socks. Gloves and socks that are already impregnated with emollients, making

application to the hands and feet more convenient, are also available. When

large areas of the body must be covered, cotton cloth topped by an ex-pandable

stockinette can be used. Disposable diapers or cloths folded in diaper fashion

are useful for dressing the groin and the perineal

areas. Axillary dressings can be made of cotton cloth, or a commercially

prepared dressing may be used and taped in place or held by dress shields. A

turban or plastic shower cap is useful for holding dressings on the scalp. A

face mask, made from gauze with holes cut out for the eyes, nose, and mouth,

may be held in place with gauze ties looped through holes cut in the four

corners of the mask. See the Plan of Nursing Care 56-1 for more information.

Related Topics