Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Dermatologic Problems

Malignant Melanoma

MALIGNANT MELANOMA

A

malignant melanoma is a cancerous neoplasm in which atypi-cal melanocytes (ie,

pigment cells) are present in the epidermis and the dermis (and sometimes the

subcutaneous cells). It is the most lethal of all the skin cancers and is

responsible for about 2% of all cancer deaths (Odom et al., 2000).

It

can occur in one of several forms: superficial spreading melanoma,

lentigo-maligna melanoma, nodular melanoma, and acral-lentiginous melanoma.

These types have specific clinical and histologic features as well as different

biologic behaviors. Most melanomas arise from cutaneous epidermal melanocytes,

but some appear in preexisting nevi (ie, moles) in the skin or de-velop in the

uveal tract of the eye. Melanomas occasionally ap-pear simultaneously with

cancer of other organs.

The

worldwide incidence of melanoma doubles every 10 years, a rise that is probably

related to increased recreational sun expo-sure and better methods of early

detection. Peak incidence occurs between ages 20 and 45. The incidence of

melanoma is increas-ing faster than that of almost any other cancer, and the

mortality rate is increasing faster than that of any other cancer except lung

cancer. The estimated number of new cases in 2002 is 53,600 and the number of

deaths is 7400 (American Cancer Society, 2002).

Risk Factors

The

cause of malignant melanoma is unknown, but ultraviolet rays are strongly

suspected, based on indirect evidence such as the increased incidence of

melanoma in countries near the equator and in people younger than age 30 who

have used a tanning bed more than 10 times per year. In general, 1 in 100

Caucasians will get melanoma every year. Up to 10% of melanoma patients are

members of melanoma-prone families who have multiple chang-ing moles (ie,

dysplastic nevi) that are susceptible to malignant transformation. Patients

with dysplastic nevus syndrome have been found to have unusual moles, larger

and more numerous moles, lesions with irregular outlines, and pigmentation

located all over the skin. Microscopic examination of dysplastic moles shows

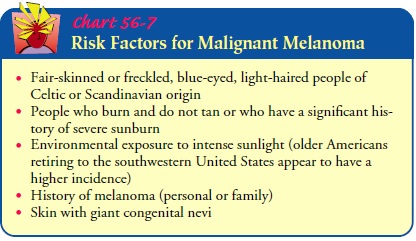

disordered, faulty growth. Chart 56-7 lists risk factors for malignant

melanoma.

Research has identified a gene that resides on chromosome 9p, the absence of which increases the likelihood that potentially mutagenic DNA damage will escape repair before cell division. The absence of this gene can be identified in melanoma-prone families (Piepkorn, 2000).

Clinical Manifestations

Superficial

spreading melanoma occurs anywhere on the body and is the most common form of

melanoma. It usually affects middle-aged people and occurs most frequently on

the trunk and lower extremities. The lesion tends to be circular, with

irregular outer portions. The margins of the lesion may be flat or elevated and

palpable (Fig. 56-7). This type of melanoma may appear in a combination of colors,

with hues of tan, brown, and black mixed with gray, blue-black, or white.

Sometimes a dull pink rose color can be seen in a small area within the lesion.

LENTIGO-MALIGNA MELANOMAS

Lentigo-maligna

melanomas are slowly evolving, pigmented le-sions that occur on exposed skin

areas, especially the dorsum of the hand, the head, and the neck in elderly

people. Often, the le-sions are present for many years before they are examined

by a physician. They first appear as tan, flat lesions, but in time, they undergo

changes in size and color.

NODULAR MELANOMA

Nodular melanoma is a spherical, blueberry-like nodule with a relatively smooth surface and a relatively uniform, blue-black color (see Fig. 56-7). It may be dome shaped with a smooth sur-face. It may have other shadings of red, gray, or purple. Some-times, nodular melanomas appear as irregularly shaped plaques.

The

patient may describe this as a blood blister that fails to re-solve. A nodular

melanoma invades directly into adjacent dermis (ie, vertical growth) and

therefore has a poorer prognosis.

ACRAL-LENTIGINOUS MELANOMA

Acral-lentiginous

melanoma occurs in areas not excessively ex-posed to sunlight and where hair

follicles are absent. It is found on the palms of the hands, on the soles, in

the nail beds, and in the mucous membranes in dark-skinned people. These

melanomas appear as irregular, pigmented macules that develop nodules. They may

become invasive early.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Biopsy results confirm the diagnosis of melanoma.

An excisional biopsy specimen provides histologic information on the type,

level of invasion, and thickness of the lesion. An excisional biopsy specimen

that includes a 1-cm margin of normal tissue and a por-tion of underlying subcutaneous

fatty tissue is sufficient for staging a melanoma in situ or an early,

noninvasive melanoma. Incisional biopsy should be performed when the suspicious

lesion is too large to be removed safely without extensive scarring. Biopsy

spec-imens obtained by shaving, curettage, or needle aspiration are not

considered reliable histologic proof of disease.

A thorough history and physical examination should

include a meticulous skin examination and palpation of regional lymph nodes

that drain the lesional area. Because melanoma occurs in families, a positive

family history of melanoma is investigated so that first-degree relatives, who

may be at high risk for melanoma, can be evaluated for atypical lesions. After

the diagnosis of mel-anoma has been confirmed, a chest x-ray, complete blood

cell count, liver function tests, and radionuclide or computed to-mography

scans are usually ordered to stage the extent of disease.

Prognosis

The prognosis for long-term (5-year) survival is

considered poor when the lesion is more than 1.5 mm thick or there is regional

lymph node involvement. A person with a thin lesion and no lymph node

involvement has a 3% chance of developing metastases and a 95% chance of

surviving 5 years. If regional lymph nodes are in-volved, there is a 20% to 50%

chance of surviving 5 years. Patients with melanoma on the hand, foot, or scalp

have a better prognosis; those with lesions on the torso have an increased

chance of metas-tases to the bone, liver, lungs, spleen, and central nervous

system. Men and elderly patients also have poor prognoses (Demis, 1998).

Medical Management

Treatment depends on the level of invasion and the

depth of the lesion. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice for small,

su-perficial lesions. Deeper lesions require wide local excision, after which

skin grafting may be needed. Regional lymph node dis-section is commonly

performed to rule out metastasis, although new surgical approaches call for

only sentinel node biopsy. This technique is used to sample the nodes nearest

the tumor and spares the patient the long-term sequelae of extensive removal of

lymph nodes if the sample node is negative (Wagner, 2000).

Immunotherapy has had varied success. Immunotherapy

mod-ifies immune function and other biologic responses to cancer. Several forms

of immunotherapy (eg, bacillus Calmette-Guérin [BCG] vaccine, Corynebacterium parvum, levamisole)

offer en-couraging results. Some investigational therapies include biologic

response modifiers (eg, interferon-alpha, interleukin-2), adaptive

immunotherapy (ie, lymphokine-activated killer cells), and mono-clonal

antibodies directed at melanoma antigens. One of these, proleukin, shows

promise in preventing recurrence of melanoma (Demis, 1998). Under investigation

is the laboratory assay of ty-rosinase, an enzyme believed to be produced only

by melanoma cells (Demis, 1998). Several other studies are attempting to

develop autologous immunization against specific tumor cells. These stud-ies

are still in the early experimental stage but show promise of pro-ducing a

vaccine against melanoma (Piepkorn, 2000).

Current treatments for metastatic melanoma are

largely un-successful, with cure generally impossible. Further surgical

inter-vention may be performed to debulk the tumor or to remove part of the

organ involved (eg, lung, liver, or colon). The rationale for more extensive

surgery, however, is for relief of symptoms, not for cure. Chemotherapy for

metastatic melanoma may be used; however, only a few agents (eg, dacarbazine,

nitrosoureas, cis-platin) have been effective in controlling the disease.

When

the melanoma is located in an extremity, regional per-fusion may be used; the

chemotherapeutic agent is perfused di-rectly into the area that contains the

melanoma. This approach delivers a high concentration of cytotoxic agents while

avoiding systemic, toxic side effects. The limb is perfused for 1 hour with

high concentrations of the medication at temperatures of 39°C to 40°C (102.2°F to 104°F) with a perfusion

pump. Inducing hyperthermia enhances the effect of the chemotherapy so that a

smaller total dose can be used. It is hoped that regional perfusion can control

the metastasis, especially if it is used in combination with surgical excision

of the primary lesion and with regional lymph node dissection.

Related Topics