Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Dermatologic Problems

Psoriasis - Noninfectious Inflammatory Dermatoses

Noninfectious Inflammatory

Dermatoses

PSORIASIS

Psoriasis is a chronic noninfectious inflammatory

disease of the skin in which epidermal cells are produced at a rate that is

about six to nine times faster than normal. The cells in the basal layer of the

skin divide too quickly, and the newly formed cells move so rapidly to the skin

surface that they become evident as profuse scales or plaques of epidermal

tissue. The psoriatic epidermal cell may travel from the basal cell layer of

the epidermis to the stratum corneum (ie, skin surface) and be cast off in 3 to

4 days, which is in sharp con-trast to the normal 26 to 28 days. As a result of

the increased num-ber of basal cells and rapid cell passage, the normal events

of cell maturation and growth cannot take place. This abnormal process does not

allow the normal protective layers of the skin to form.

One of the most common skin diseases, psoriasis

affects ap-proximately 2% of the population, appearing more often in people who

have a European ancestry. It is thought that the con-dition stems from a

hereditary defect that causes overproduction of keratin. Although the primary

cause is unknown, a combina-tion of specific genetic makeup and environmental

stimuli may trigger the onset of disease. There is some evidence that the cell

proliferation is mediated by the immune system. Periods of emo-tional stress

and anxiety aggravate the condition. Trauma, infec-tions, and seasonal and

hormonal changes also are trigger factors. The onset may occur at any age but

is most common between the ages of 15 and 50 years. Psoriasis has a tendency to

improve and then recur periodically throughout life (Champion et al., 1998).

Clinical Manifestations

Lesions appear as red, raised patches of skin

covered with silvery scales. The scaly patches are formed by the buildup of

living and dead skin resulting from the vast increase in the rate of skin-cell

growth and turnover (Fig. 56-4). If the scales are scraped away, the dark red

base of the lesion is exposed, producing multiple bleeding points. These

patches are not moist and may be pruritic. One variation of this condition is called

guttate psoriasis because the lesions remain about 1 cm wide and are scattered

like rain-drops over the body. This variation is believed to be associated with

a recent streptococcal throat infection. Psoriasis may range in severity from a

cosmetic source of annoyance to a physically disabling and disfiguring

disorder.

Particular sites of the body tend to be affected most by this condition; they include the scalp, the extensor surface of the el-bows and knees, the lower part of the back, and the genitalia. Bi-lateral symmetry is a feature of psoriasis. In approximately one fourth to one half of patients, the nails are involved, with pitting, discoloration, crumbling beneath the free edges, and separation of the nail plate. When psoriasis occurs on the palms and soles, it can cause pustular lesions called palmar pustular psoriasis.

Complications

The disease may be associated with asymmetric

rheumatoid factor– negative arthritis of multiple joints. The arthritic

development can occur before or after the skin lesions appear. The relation

between arthritis and psoriasis is not understood. Another complication is an

exfoliative psoriatic state in which the disease progresses to in-volve the

total body surface, called erythrodermic psoriasis. In this case, the patient

is more acutely ill, with fever, chills, and an elec-trolyte imbalance.

Erythrodermic psoriasis often appears in people with chronic psoriasis after

infections or after exposure to certain medications, including withdrawal of

systemic corticosteroids (Champion et al., 1998).

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The presence of the classic plaque-type lesions

generally confirms the diagnosis of psoriasis. Because the lesions tend to

change his-tologically as they progress from early to chronic plaques, biopsy

of the skin is of little diagnostic value. There are no specific blood tests

helpful in diagnosing the condition. When in doubt, the health professional

should assess for signs of nail and scalp involvement and for a positive

family history.

Medical Management

The goals of management are to slow the rapid

turnover of epi-dermis, to promote resolution of the psoriatic lesions, and to

con-trol the natural cycles of the disease. There is no known cure.

The therapeutic approach should be one that the

patient under-stands; it should be cosmetically acceptable and not too

disrup-tive of lifestyle. Treatment involves the commitment of time and effort

by the patient and possibly the family. First, any precipi-tating or aggravating

factors are addressed. An assessment is made of lifestyle, because psoriasis is

significantly affected by stress. The patient is informed that treatment of

severe psoriasis can be time consuming, expensive, and aesthetically

unappealing at times.

The

most important principle of psoriasis treatment is gen-tle removal of scales.

This can be accomplished with baths. Oils (eg, olive oil, mineral oil, Aveeno

Oilated Oatmeal Bath) or coal tar preparations (eg, Balnetar) can be added to

the bath water and a soft brush used to scrub the psoriatic plaques gently.

After bathing, the application of emollient creams containing alpha-hydroxy

acids (eg, Lac-Hydrin, Penederm) or salicylic acid will continue to soften

thick scales. The patient and family should be encouraged to establish a

regular skin care routine that can be maintained even when the psoriasis is not

in an acute stage.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

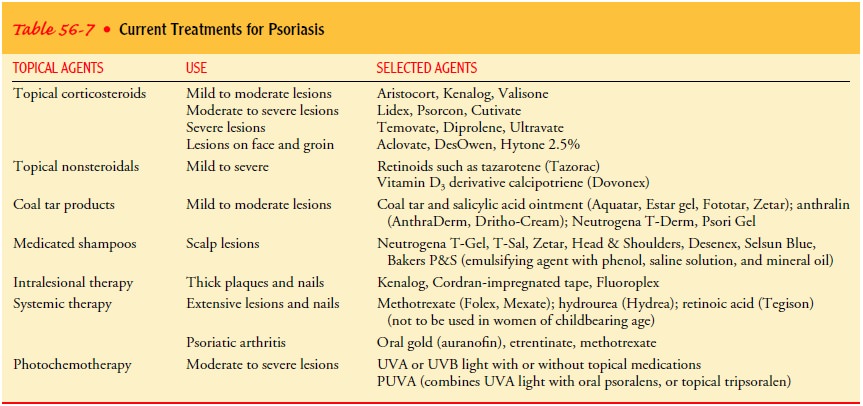

Three

types of therapy are standard: topical, intralesional, and systemic (Table

56-7).

Topical Agents.

Topically applied agents are used to slow the overactive epidermis without affecting other tissues. Medications include tar preparations, anthralin, salicylic acid, and cortico-steroids. Two topical treatments introduced within the last few years are a vitamin D preparation, calcipotriene (Dovonex), and a retinoid compound, tazarotene (Tazorac). Treatment with these agents tends to suppress epidermopoiesis (ie, development of epidermal cells) and cause sloughing of the rapidly growing epi-dermal cells.

Topical formulations include lotions, ointments,

pastes, creams, and shampoos. Older treatments, including tar baths and

appli-cation of tar preparations on involved skin, are rarely used. Tar and

anthralin cause irritation of the skin at the sites of applica-tion, are

malodorous and difficult to apply, and do not give reli-able results. Newer

preparations that cause less irritation and have more consistent results are

becoming more widely used.

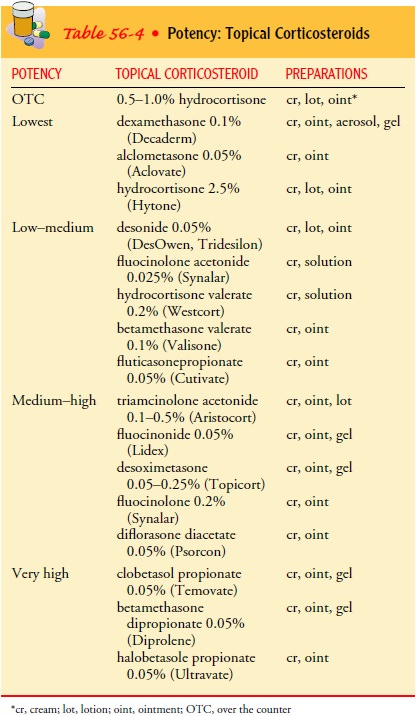

Topical

corticosteroids may be applied for their anti-inflammatory effect. Choosing the

correct strength of cortico-steroid for the involved site and choosing the most

effective vehicle base are important aspects of topical treatment. In general,

high-potency topical corticosteroids should not be used on the face and

intertriginous areas, and their use on other areas should be limited to a

4-week course of twice-daily applications. A 2-week break should be taken

before repeating treatment with the high-potency corticosteroids. For long-term

therapy, moderate-potency corti-costeroids are used. On the face and

intertriginous areas, only low-potency corticosteroids are appropriate for

long-term use (see Table 56-4).

Occlusive dressings may be applied to increase the

effective-ness of the corticosteroid. For the hospitalized patient, large

plas-tic bags may be used—one for the upper body with openings cut for the head

and arms and one for the lower body with openings for the legs. This leaves

only the extremities to wrap. In some der-matologic units, large rolls of

tubular plastic are used, such as those used by dry-cleaners. For patients

being treated at home, a vinyl jogging suit may be used. The medication is

applied, and the suit is put on over it. The hands can be wrapped in gloves,

the feet in plastic bags, and the head in a shower cap. Occlusive dress-ings

should not remain in place longer than 8 hours. The nurse should very carefully

inspect the skin for the appearance of atro-phy and telangiectasias which are

side effects of corticosteroids.

When

psoriasis involves large areas of the body, topical corti-costeroid treatment

can become expensive and involve some sys-temic risk. Some potent

corticosteroids, when applied to large areas of the body, have the potential to

cause adrenal suppression through percutaneous absorption of the medication. In

this event, other treatment modalities (eg, nonsteroidal topical med-ications,

ultraviolet light) may be used instead or in combination to decrease the need

for corticosteroids.

Newer nonsteroidal topical preparations are

available and ef-fective for many patients. Calcipotriene 0.05% (Dovonex) is a

derivative of vitamin D2. It works to decrease the mitotic turnover of the

psoriatic plaques. Its most common side effect is local irri-tation, and the

intertriginous areas and face should be avoided when using this medication.

Patients should be monitored for symptoms of hypercalcemia. It is available as

a cream for use on the body and a solution for the scalp. Calcipotriene is not

rec-ommended for use by elderly patients because of their more frag-ile skin or

for pregnant or lactating women.

The second advance in topical treatment of

psoriasis is tazarotene (Tazorac). Tazarotene, a retinoid, causes sloughing of

the scalescovering psoriatic plaques. As with other retinoids, it

causes in-creased sensitivity to sunlight, so patients should be cautioned to

use an effective sunscreen and avoid other photosensitizers (eg, tetracycline,

antihistamines). Tazarotene is listed as a Cate-gory X drug in pregnancy;

reports indicate evidence of fetal risk, and the risk of use in pregnant women

clearly outweighs any possible benefits. A negative result on a pregnancy test

should be obtained before initiating this medication, and an effective

contraceptive should be continued during treatment. Side effects of tazarotene

include burning, erythema, or irritation at the site of application and

worsening of psoriasis.

Intralesional Agents.

Intralesional injections of triamcinolone acetonide

(Aristocort, Kenalog-10, Trymex) can be administered directly into highly

visible or isolated patches of psoriasis that are resistant to other forms of

therapy. Care must be taken to ensure that normal skin is not injected with the

medication.

Systemic Agents.

Although systemic corticosteroids may cause rapid

improvement of psoriasis, their usual risks and the possi-bility of triggering

a severe flare-up on withdrawal limit their use. Systemic cytotoxic

preparations, such as methotrexate, have been used in treating extensive

psoriasis that fails to respond to other forms of therapy. Other systemic

medications in current use in-clude hydroxyurea (Hydrea) and cyclosporine A

(CyA).

Methotrexate

appears to inhibit DNA synthesis in epidermal cells, thereby reducing the

turnover time of the psoriatic epider-mis. However, the medication can be

toxic, especially to the liver, which can suffer irreversible damage.

Laboratory studies must be monitored to ensure that the hepatic, hematopoietic,

and renal systems are functioning adequately. Bone marrow suppression is another

potential side effect. The patient should avoid drinking alcohol while taking

methotrexate, because alcohol ingestion in-creases the possibility of liver

damage. The medication is terato-genic (ie, producing physical defects in the

fetus) and should not be administered to pregnant women.

Hydroxyurea

also inhibits cell replication by affecting DNA synthesis. The patient is

monitored for signs and symptoms of bone marrow depression.

Cyclosporine

A, a cyclic peptide used to prevent rejection of transplanted organs, has shown

some success in treating severe, therapy-resistant cases of psoriasis. Its use,

however, is limited by side effects such as hypertension and nephrotoxicity.

Oral

retinoids (ie, synthetic derivatives of vitamin A and its metabolite, vitamin A

acid) modulate the growth and differenti-ation of epithelial tissue. Etretinate

is especially useful for severe pustular or erythrodermic psoriasis. Etretinate

is a teratogen with a very long half-life; it cannot be used in women with

childbearing potential.

PHOTOCHEMOTHERAPY

One treatment for severely debilitating psoriasis

is a psoralen medication combined with ultraviolet-A (PUVA) light therapy.

Ultraviolet light is the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum containing

wavelengths ranging from 180 to 400 nm. In this treatment, the patient takes a

photosensitizing medication (usu-ally 8-methoxypsoralen) in a standard dose and

is subsequently exposed to long-wave ultraviolet light as the medication plasma

levels peak. Although the mechanism of action is not completely understood, it

is thought that when psoralen-treated skin is exposed to ultraviolet-A light,

the psoralen binds with DNA and decreases cellular proliferation. PUVA is not

without its hazards;it has been associated with long-term risks of skin cancer,

cataracts, and premature aging of the skin.

The

PUVA unit consists of a chamber that contains high-output black-light lamps and

an external reflectance system. The exposure time is calibrated according to

the specific unit in use and the anticipated tolerance of the patient’s skin.

The patient is usually treated two or three times each week until the psoriasis

clears. An interim period of 48 hours between treatments is nec-essary because

it takes this long for any burns resulting from PUVA therapy to become evident.

After

the psoriasis clears, the patient begins a maintenance program. Once little or

no disease is active, less potent therapies are used to keep minor flare-ups

under control.

Ultraviolet-B (UVB) light therapy is also used to

treat general-ized plaques. UVB light ranges from 270 to 350 nm, although

re-search has shown that a narrow range, 310 to 312 nm, is the action spectrum.

It is used alone or combined with topical coal tar. Side effects are similar to

those of PUVA therapy. A new development in light therapy is the narrow-band

UVB, which ranges from 311 to 312 nm, decreasing exposure to harmful

ultraviolet energy while providing more intense, specific therapy (Shelk &

Morgan, 2000).

If access to a light treatment unit is not

feasible, the patient can expose himself or herself to sunlight. The risks of

all light treatments are similar and include acute sunburn reaction;

exac-erbation of photosensitive disorders such as lupus, rosacea, and

polymorphic light eruption; and other skin changes such as in-creased wrinkles,

thickening, and an increased risk for skin cancer.

Excimer

lasers have come into use in treating psoriasis. These lasers function at 308

nm. Studies show that medium-sized pso-riatic plaques clear in four to six

treatments and remain clear for up to 9 months. A laser can be more effective

on the scalp or on other hard-to-treat areas, because the laser can be aimed

very specifically on the plaque (Lebwohl, 2000). Table 56-7 summa-rizes the

treatment plans.

Related Topics