Chapter: Biochemistry: Carbohydrates

What happens if a sugar forms a cyclic molecule?

What happens if a sugar forms a

cyclic molecule?

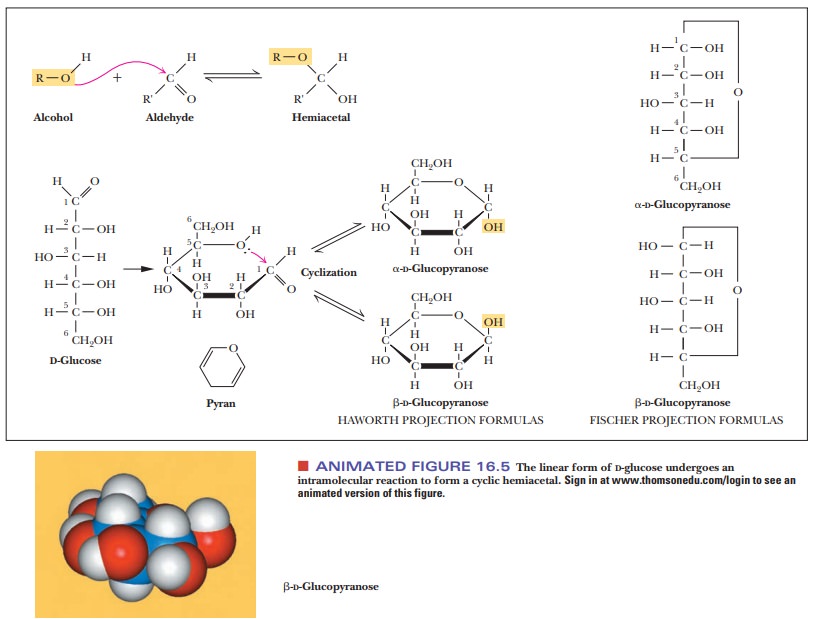

Sugars, especially those with five or six carbon atoms, normally exist as cyclic molecules rather than as the open-chain forms we have shown so far. The cyclization takes place as a result of interaction between the functional groups on distant carbons, such as C-1 and C-5, to form a cyclic hemiacetal (in aldohexoses). Another possibility (Figure 16.5) is interaction between C-2 and C-5 to form a cyclic hemiketal (in ketohexoses). In either case, the carbonyl carbon becomes a new chiral center called the anomeric carbon. The cyclic sugar can take either of two different forms, designated α and β, and are called anomers of each other.

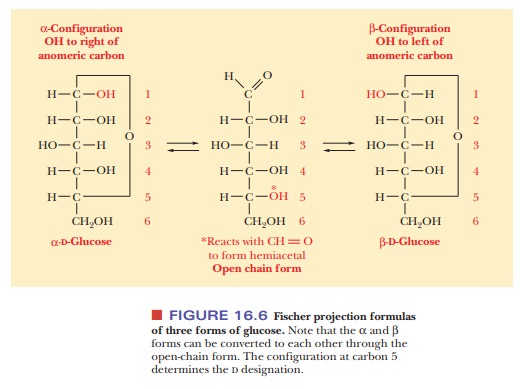

The

Fischer projection of the α-anomer of a D sugar has the anomeric hydroxyl group

to the right of the anomeric carbon (C—OH), and the β-anomer of aDsugar has the anomeric hydroxyl group to the left of

theanomeric carbon (Figure 16.6). The free carbonyl species can readily form

either the α- or β-anomer, and the anomers can be converted from

one form to another through the free carbonyl species. In some biochemical

molecules, any anomer of a given sugar can be used, but, in other cases, only

one anomer occurs. For example, in living organisms, only β-D-ribose and β-D-deoxyribose are found in RNA and DNA,

respectively.

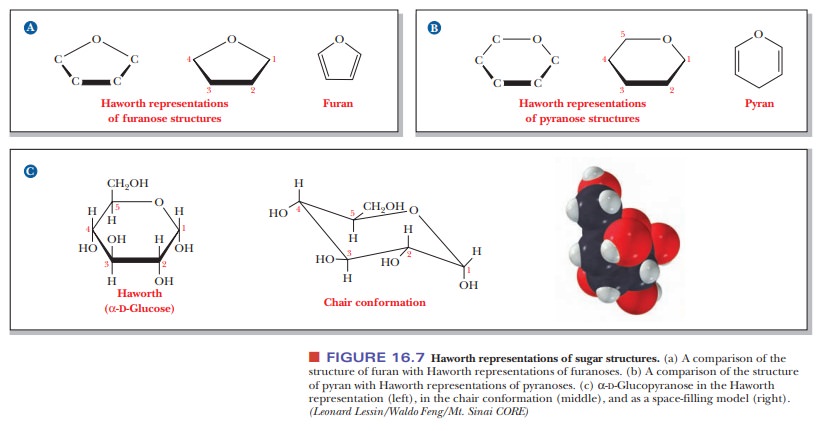

Fischer projection formulas are useful for describing the stereochemistry of sugars, but their long bonds and right-angle bends do not give a realistic picture of the bonding situation in the cyclic forms, nor do they accurately represent the overall shape of the molecules. Haworth projection formulas are more useful for those purposes. In Haworth projections, the cyclic structures of sugars are shown in perspective drawings as planar five- or six-membered rings viewed nearly edge on. A five-membered ring is called a furanose because of its resemblance to furan; a six-membered ring is called a pyranose because of its resemblance to pyran [Figure 16.7(a) and (b)].

These cyclic formulas approximate the shapes of the actual molecules

better for furanoses than for pyranoses. The five-membered rings of furanoses

are in reality very nearly pla-nar, but the six-membered rings of pyranoses

actually exist in solution in the chair conformation [Figure 16.7(c)]. This

kind of structure is particularly use-ful in discussions of molecular

recognition. The chair conformation and the Haworth projections are alternative

ways of expressing the same information. Even though the Haworth formulas are

approximations, they are useful short-hand for the structures of reactants and

products in many reactions that we are going to see. The Haworth projections

represent the stereochemistry of sugars more realistically than do the Fischer

projections, and the Haworth scheme is adequate for our purposes. That is why

biochemists use them, even though organic chemists prefer the chair form. We

shall continue to use Haworth pro-jections in our discussion of sugars.

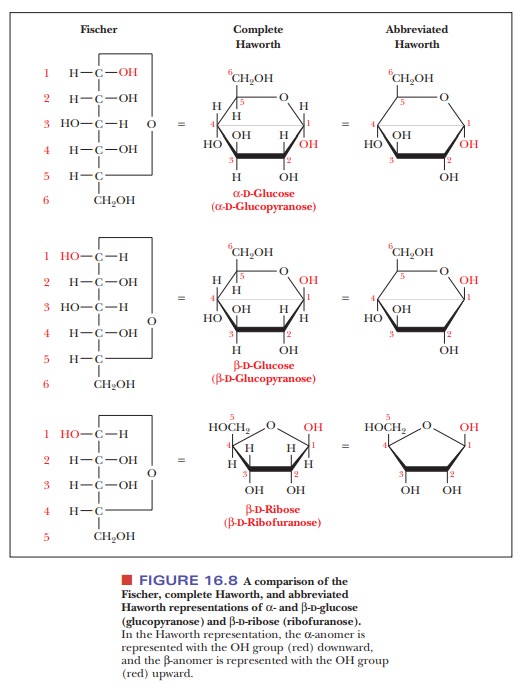

For a D

sugar, any group that is written to the right

of the carbon in a Fischer projection has a downward

direction in a Haworth projection; any group that is written to the left in a Fischer projection has an upward direction in a Haworth

projection. The terminal —CH2OH group, which contains the carbon

atom with the highest number in the numbering scheme, is shown in an upward

direction. The structures of α- and β-D-glucose, which are both pyranoses, and of β-D-ribose, which is a furanose, illustrate this point (Figure

16.8). Note that, in the α-anomer, the hydroxyl on the anomeric carbon is

on the opposite side of the ring from the terminal —CH2OH group

(i.e., pointing down). In the β-anomer, it is on the same side of the ring

(pointing up). The same conven-tion holds for α- and β-anomers of furanoses.

Related Topics