Chapter: Introduction to Human Nutrition: The Vitamins

Vitamins: Introduction - Human Nutrition

The Vitamins

Introduction

In order to demonstrate that a compound is a vitamin, it is

necessary to demonstrate both that deprivation of experimental subjects will

lead to the development of a more or less specific clinical deficiency disease

and abnormal metabolic signs, and that restoration of the missing compound will

prevent or cure the deficiency disease and normalize metabolic abnormalities.

It is not enough simply to demonstrate that a compound has a function in the

body, since it may normally be synthesized in adequate amounts to meet

requirements, or that a compound cures a disease, since this may simply reflect

a pharmacological action and not indicate that the compound is a dietary

essential.

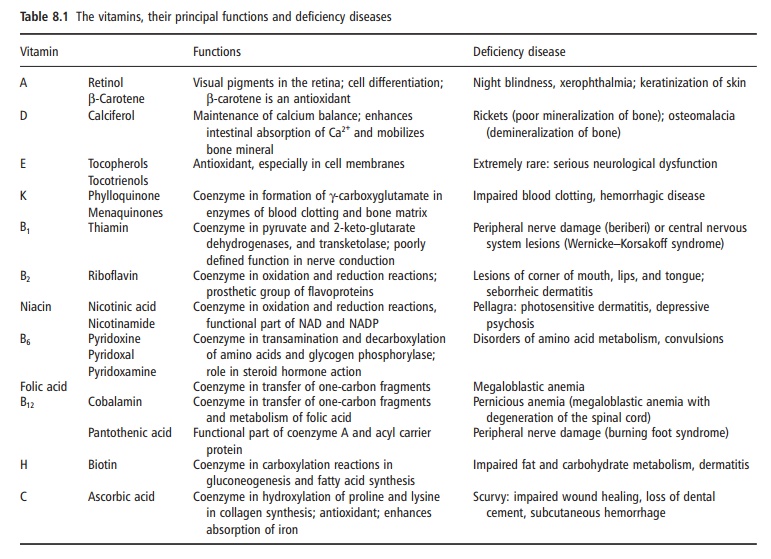

The vitamins, and their principal functions and deficiency

signs, are shown in Table 8.1; the curious nomenclature is a consequence of the

way in which they were discovered at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Early studies showed that there was some-thing in milk that was essential, in

very small amounts, for the growth of animals fed on a diet consisting of

purified fat, carbohydrate, protein, and mineral salts.

Two factors were found to be essential: one was found in the

cream and the other in the watery part of milk. Logically, they were called

factor A (fat-soluble, in the cream) and factor B (water-soluble, in the watery

part of the milk). Factor B was identified chemically as an amine, and in 1913

the name “vitamin” was coined for these “vital amines.”

Further studies showed that “vitamin B” was a mixture of a

number of compounds, with different actions in the body, and so they were given

numbers as well: vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and so on. There

are gaps in the numerical order of the B vitamins. When what might have been

called vitamin B3 was discovered, it was found to be a chemical

compound that was already known, nicotinic acid. It was therefore not given a

number. Other gaps are because compounds that were assumed to be vitamins and

were given numbers, such as B4 and B5, were later shown

either not to be vitamins, or to be vitamins that had already been described by

other workers and given other names.

Vitamins C, D and E were named in the order of their discovery.

The name “vitamin F” was used at one time for what we now call the essential

fatty acids; “vitamin G” was later found to be what was already

As the chemistry of the vitamins was elucidated, so they were

given names as well, as shown in Table 8.1. When only one chemical compound has

the biologi-cal activity of the vitamin, this is quite easy. Thus, vitamin B1

is thiamin, vitamin B2 is riboflavin, etc. With several of the

vitamins, a number of chemically related compounds found in foods can be

intercon-verted in the body, and all show the same biological activity. Such

chemically related compounds are called vitamers, and a general name (a generic

descrip-tor) is used to include all compounds that display the same biological

activity.

Some compounds have important metabolic func-tions, but are not

considered to be vitamins, since, as far as is known, they can be synthesized

in the body in adequate amounts to meet requirements. These include carnitine,

choline, inositol, taurine, and ubiquinone.

Two compounds that are generally considered to be vitamins can

be synthesized in the body, normally in adequate amounts to meet requirements:

vitamin D, which is synthesized from 7-dehydrocholesterol in the skin on

exposure to sunlight, and niacin, which is synthesized from the essential amino

acid tryptophan. However, both were discovered as a result of studies of

deficiency diseases that were, during the early twentieth century, significant

public health problems: rickets (due to vitamin D deficiency and inadequate

sunlight exposure) and pellagra (due to deficiency of both tryptophan and

preformed niacin).

Related Topics