Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Emergency Nursing

Violence, Abuse, and Neglect - Emergency Nursing

Violence,

Abuse, and Neglect

FAMILY VIOLENCE, ABUSE, AND NEGLECT

EDs are often the first

place where victims of family violence, abuse, or neglect go to seek help. Each

year in the United States 3 to 4 million women experience domestic violence,

and up to one third of all women will be in a domestic violence situation in

their lifetime. One million women are severely beaten each year. Approximately

2 to 3 million children are seriously abused, an additional 5 million children

are maltreated, and 1 to 2 million elders are abused or neglected (Guth,

Pachter, 2000). Among women who are pregnant, 4% to 14% will suffer physical

vio-lence from their intimate partner, with 10% to 24% of this pop-ulation

having been abused during the year before they became pregnant. These

statistics are startlingly higher for teenagers, of whom 20% are assaulted

while pregnant. The severity of the abuse increases and is associated with

battering during pregnancy. Domestic violence is the leading cause of death for

young African American women (Campbell, 1999; Harrell et al., 2002). On the

average, between 6% and 28% of women seen in the ED have suffered abuse, with

up to 6% of these patients seeking treatment for a complaint related to a

recent event. Between 20% and 35% of all ED visits relate to continuous abuse.

Young women are most likely to suffer nonlethal violent acts that result in

visits to the ED (Moskowitz, Griffith, DiScala, & Sege, 2001). ED nurses

must be aware that men and persons with disabilities are also victims of

domestic violence and should include questions to that effect in their

evaluations. Elder abuse takes many forms, including physical and psychological

abuse, neglect, violation of personal rights, and financial abuse.

Clinical Manifestations

When victims of abuse seek treatment, they may present

with physical injuries or with health problems, such as anxiety, in-somnia, or

gastrointestinal symptoms, that are related to stress. They usually do not

identify their abuser.

The possibility of abuse should be investigated whenever

a person presents with multiple injuries that are in various stages of healing,

when injuries are unexplained, and when the expla-nation does not fit the

physical picture (Chart 71-13). The pos-sibility of neglect should be

investigated whenever a dependent person with adequate resources and a

designated care provider shows evidence of inattention to hygiene, to

nutrition, or to known medical needs (eg, unfilled medication prescriptions,

missed appointments with health care providers). In the ED, the most common

physical injuries seen are unexplained bruises, lacerations, abrasions, head

injuries, or fractures. The most com-mon clinical manifestations of neglect are

malnutrition and de-hydration.

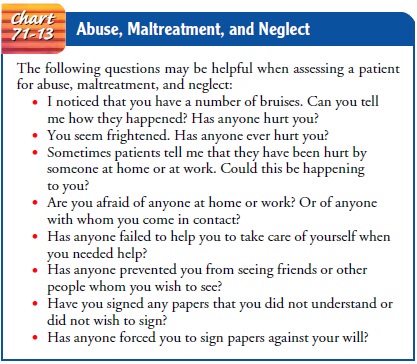

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Nurses in EDs are in an ideal position to provide early

detection and interventions for victims of domestic violence. This requires an

acute awareness of the signs of possible abuse, maltreatment, and neglect.

Nurses must be skilled in interviewing techniques that are likely to elicit

accurate information. A careful history is crucial in the screening process.

Asking questions in private— away from others—may be helpful in eliciting

information about abuse, maltreatment, and neglect.

Whenever evidence leads one to suspect abuse or neglect,

an evaluation with careful documentation of descriptions of events and drawings

or photos of injuries is important, because the med-ical record may be used as

part of a legal document. Assessment of the patient’s general appearance and

interactions with signifi-cant others, an examination of the entire surface

area of the body, and a mental status examination are crucial.

Management

Whenever abuse, maltreatment, or neglect is suspected,

the health care worker’s primary concern should be the safety and welfare of

the patient. Treatment focuses on the consequences of the abuse, violence, or

neglect and on prevention of further injury. Protocols of most EDs require that

a multidisciplinary ap-proach be used. Nurses, physicians, social workers, and

commu-nity agencies work collaboratively to develop and implement a plan for

meeting the patient’s needs.

If in immediate danger, the patient should be separated

from the abusing or neglecting person whenever possible. On the basis of this

danger, or on the basis of injuries or neglected medical conditions, hospitalization

is justified until alternative plans are made. However, it must be remembered

that third-party payers may not approve hospitalization that is based solely on

abuse or neglect.

When abuse or neglect is considered to be the result of

stress experienced by a caregiver who is no longer able to cope with the burden

of caring for an elderly person or a person with chronic disease or a

disability, respite services may be necessary. Support groups may be helpful to

these caregivers. When mental illness of the abuser or neglecter is responsible

for the situation, alternative living arrangements may be required.Nurses must

be mindful that competent adults are free to ac-cept or refuse the help that is

offered to them. Some patients will insist on remaining in the home environment

where the abuse or neglect is occurring. The wishes of patients who are

competent and not cognitively impaired should be respected. However, all

possible alternatives and available resources should be explored with the

patient.

Mandatory reporting laws in most states require health

care workers to report suspected

abuse to an official agency, usually Adult (or Child) Protective Services. All

that is required for re-porting is the suspicion of abuse. The health care

worker is not required to prove anything. Likewise, health care workers who

re-port suspected abuse are immune to civil or criminal liability if the report

is made in good faith. Subsequent home visits result-ing from the report of

suspected abuse are a part of gathering information about the patient in the

home environment. In addition, many states have resource hotlines for use by

health care workers and by patients who seek answers to questions about abuse

and neglect.

SEXUAL ASSAULT

The definition of rape is forced sexual acts, especially

vaginal or anal penetration. Perpetrators and victims may be either male or

female. The feminist movement has focused on the rights and care of rape

victims, and law enforcement agencies are becoming increasingly sensitive and

aggressive in managing these crimes. Rape crisis centers offer support, educate

victims, and help them through the subsequent courtroom experience.

The manner in which the patient is received and treated

in the ED is important to his or her future psychological well-being. Crisis

intervention should begin when the patient enters the health care facility. The

patient should be seen immediately. Most hospitals have a written protocol that

reflects consideration for the victim’s physical and emotional needs as well as

forensic evidence collection that is required.

The Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner

In many states, there is

the opportunity for emergency nurses to become trained sexual assault nurse

examiners (SANEs). The role allows for specific training in forensic evidence

collection, history taking, documentation, and ways to approach the patient and

family. Specialized training also includes proper photography and the use of

colposcopy. Colposcopy increases assessment by examination for microtrauma

through magnification. Evidence is collected through photography, videography,

and analysis of specimens. Another tool useful to SANEs is the light-staining

microscope, which enables the examiner to identify motile and nonmotile sperm

and infection. This tool saves time and also enhances assessment. SANEs

complement the ED staff and can spend more time with both the patient and

police officers inves-tigating the incident.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The patient’s reaction to rape has been termed rape trauma syn-drome and is seen as an

acute stress reaction to a life-threateningsituation. The nurse performing the

assessment is aware that the patient may go through several phases of

psychological reactions (Dole, 1996; Ritchie, 1998):

·

An acute disorganization

phase, which may manifest as an expressed state in which shock, disbelief,

fear, guilt, humiliation, anger, and other such emotions are encountered or as

a controlled state in which feelings are masked or hidden and the victim

appears composed

·

A phase of denial and

unwillingness to talk about the inci-dent, followed by a phase of heightened

anxiety, fear, flash-backs, sleep disturbances, hyperalertness, and

psychosomatic reactions

·

A phase of reorganization, in

which the incident is put into perspective. Some victims never fully recover

and go on to develop chronic stress disorders and phobias.

Management

The goals of management are to give sympathetic support,

to re-duce the emotional trauma of the patient, and to gather available

evidence for possible legal proceedings. All of the interventions have the

ultimate goal of having the patient regain control over his or her life.

Throughout the patient’s

stay in the ED, the patient’s privacy and sensitivity must be respected. The

patient may exhibit a wide range of emotional reactions, such as hysteria,

stoicism, or feel-ings of being overwhelmed. Support and caring are crucial.

The patient should be reassured that anxiety is natural and asked whether a

support person may be called. Appropriate support is available from

professional and community resources. The Rape Victim Companion Program, if

available in the community, can be contacted, and services of a volunteer can

be requested. The patient should never be left alone.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A written, witnessed

informed consent must be obtained from the patient (or parent or guardian if

the patient is a minor) for ex-amination, for taking of photographs, and for

release of findings to police. A history is obtained only if the patient has

not already talked to a police officer, social worker, or crisis intervention

worker. The patient should not be asked to repeat the history. Any history of

the event that is obtained should be recorded in the patient’s own words. The

patient is asked whether he or she has bathed, douched, brushed teeth, changed

clothes, urinated, or defecated since the attack, because these actions may

alter in-terpretation of subsequent findings. The time of admission, time of

examination, date and time of the alleged rape, and the patient’s emotional

state and general appearance (including any evidence of trauma, such as

discoloration, bruises, lacerations, secretions, or torn and bloody clothing)

are documented.

For the physical examination, the patient is helped to

undress and is draped properly. Each item of clothing is placed in a sepa-rate

paper bag. Plastic bags are not used because they retain mois-ture; moisture

may promote mold and mildew formation, which can destroy evidence. The bags are

labeled and given to appro-priate law enforcement authorities.

The patient is examined (from head to toe) for injuries,

espe-cially injuries to the head, neck, breast, thighs, back, and but-tocks.

Body diagrams and photographs aid in documenting the evidence of trauma. The

physical examination focuses on the following:

·

External evidence of trauma

(bruises, contusions, lacerations, stab wounds)

·

Dried semen stains (appearing

as crusted, flaking areas) on the patient’s body or clothes

·

Broken fingernails and body

tissue and foreign materials under nails (if found, samples are taken)

·

Oral examination, including a

specimen of saliva and pre-scribed cultures of gum and tooth areas

Pelvic and rectal

examinations are also performed. The per-ineum and other areas are examined

with a Wood lamp or other filtered ultraviolet light. Areas that appear

fluorescent may indi-cate semen stains. The color and consistency of any

discharge pres-ent is noted. A water-moistened rather than a lubricated vaginal

speculum is used for the examination. Lubricant contains chemi-cals that may

interfere with later forensic testing of specimens and acid phosphatase

determinations. The rectum is examined for signs of trauma, blood, and semen.

During the examination, the patient should be advised of the nature and

necessity of each pro-cedure and given the rationale for each question asked.

SPECIMEN COLLECTION

During the physical

examination, numerous laboratory speci-mens may be collected, including the

following:

·

Vaginal aspirate, examined for

presence or absence of motile and nonmotile sperm

·

Secretions (obtained with a

sterile swab) from the vaginal pool for acid phosphatase, blood group antigen

of semen, and precipitin test against human sperm and blood

·

Separate smears from the oral,

vaginal, and anal areas

·

Culture of body orifices for

gonorrhea

·

Blood serum for syphilis and

HIV testing; a sample of serum for syphilis may be frozen and saved for future

testing

·

Pregnancy test if there is a

possibility that the patient may be pregnant

·

Any foreign material (leaves,

grass, dirt), which is placed in a clean envelope

·

Pubic hair samples obtained by

combing or trimming. Sev-eral pubic hairs with follicles are placed in separate

contain-ers and identified as the patient’s hairs.

To preserve the chain of evidence, each specimen is

labeled with the name of the patient, the date and time of collection, the body

area from which the specimen was obtained, and the names of personnel

collecting specimens. Then the specimens are given to a designated person (eg,

crime laboratory technician), and an itemized receipt is obtained.

TREATING POTENTIAL CONSEQUENCES OF RAPE

After the initial physical examination is completed and

specimens have been obtained, any associated injuries are treated as

indi-cated. The patient is given the option of prophylaxis against sex-ually

transmitted disease. Ceftriaxone (Rocephin), administered intramuscularly with

1% lidocaine (Xylocaine), may be pre-scribed as prophylaxis for gonorrhea.

Doxycycline (Vibramycin) taken for 10 days may be prescribed as prophylaxis for

syphilis and chlamydia.

Antipregnancy measures

may be considered if the patient is of childbearing age, is not using

contraceptives, and is at high risk in her menstrual cycle. A postcoital

contraceptive medication, such as Ovral, which contains estrogen ethinyl

estradiol and pro-gestin norgestrel, may be prescribed after a pregnancy test.

To promote effectiveness, Ovral should be administered within 12 to 24 hours

and no later than 72 hours after intercourse. The 21-day package rather than

the 28-day package is prescribed, so that the patient does not take the inert

tablets by mistake. An antiemetic may be administered as prescribed to decrease

discomfort from side effects. A cleansing douche, mouthwash, and fresh clothing

are usually offered.

FOLLOW-UP CARE

The patient is informed of counseling services to prevent

long-term psychological effects. Counseling services should be made available

to both the patient and the family. A referral is made to the Rape Victim

Companion Program, if available. Appointments for follow-up surveillance for

pregnancy, sexually transmitted disease, and HIV testing also are made.

The patient is encouraged to return to his or her

previous level of functioning as soon as possible. When leaving the health care

facility, the patient should be accompanied by a family member or friend.

VIOLENCE IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

Not only do ED staff

members encounter patients who are vio-lent from substance abuse, injury, or

other emergencies, but they may also encounter violent situations in the rest

of the environ-ment. Patients and families waiting for assistance are

increasingly volatile. Often, waiting rooms are the site for dissatisfaction,

fear, and anger to be acted out in violence. Some EDs assign security officers

to the area and have installed metal detectors to identify weapons and protect

patients, families, and staff. It is not unusual for a patient to come to the

ED armed. Nurses and other per-sonnel must be prepared to deal with such

circumstances.

Management

Safety is the first priority. Protecting the ED on a

daily basis will prevent any untoward events from occurring. Protection of the

department provides protection for the patients, families, and staff. It is

essential that all nurses be aware of the environment in which they are

working.

Metal detectors, silent alarm systems, and secured entry

into the department assist in maintaining safety. Members of gangs and feuding

families need to be separated in the ED, in the wait-ing room, and later in the

inpatient nursing unit to avoid angry confrontations. Security officers should

be ready to assist at all times. The department should be able to be locked

against entry if security is at all in question.

Patients from prison and those who are under guard need

to be shackled to the bed with appropriate assessment. The same as-sessment and

care that are provided to patients with hand or ankle restraints are provided

to patients with handcuffs. In addi-tion, the following precautions are taken:

·

Never release the hand or

ankle restraint (handcuff).

·

Always have a guard present in

the room.

·

Place the patient face down on

the stretcher to avoid injury from head-butting, spitting, or biting.

·

Use restraints on any violent

patient as needed.

·

Administer medication if

necessary to control violent be-havior until definitive treatment can be

obtained.

In the case of gunfire

in the ED, self-protection is a priority. There is no advantage to protecting

others if the caregivers are also injured. Security officers and police must

gain control of the situation first; then care is provided to the injured.

Related Topics