Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Emergency Nursing

Scope and Practice of Emergency Nursing

Scope and

Practice of Emergency Nursing

The emergency nurse has

had specialized education, training, and experience to gain expertise in

assessing and identifying patients’ health care problems in crisis situations.

In addition, the emer-gency nurse establishes priorities, monitors and

continuously as-sesses acutely ill and injured patients, supports and attends

to families, supervises allied health personnel, and teaches patients and

families within a time-limited, high-pressured care environ-ment. Nursing

interventions are accomplished interdependently, in consultation with or under

the direction of a licensed physi-cian or nurse practitioner. The strengths of

nursing and medicine are complementary in an emergency situation. Appropriate

nurs-ing and medical interventions are anticipated based on assess-ment data.

The emergency health care staff members work as a team in performing the highly

technical, hands-on skills required to care for patients in an emergency

situation.

The nursing process provides a

logical framework for problem solving in this environment. Patients in the ED

have a wide variety of actual or potential problems, and their condition may

change constantly. Therefore, nursing assessment must be continuous, and

nursing diagnoses change with the patient’s condition. Although a patient may

have several diagnoses at a given time, the focus is on the most

life-threatening ones; often, both independent and interdependent nursing

interventions are required.

ISSUES IN EMERGENCY NURSING CARE

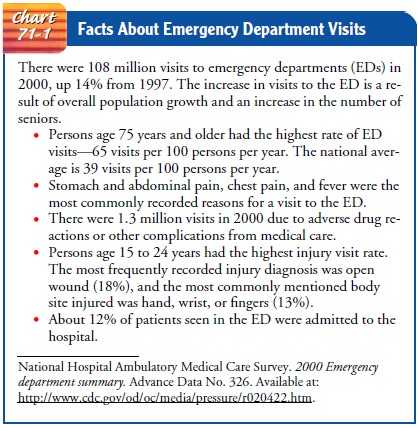

Emergency nursing is

demanding because of the diversity of con-ditions and situations that, if not

unique to the ED, certainly pre-sent a challenge (Chart 71-1). These issues

include legal issues, occupational health and safety risks for ED staff, and

the chal-lenge of providing holistic care in the context of a fast-paced,

technology-driven environment in which serious illness and death are confronted

on a daily basis. Another dimension of emergency nursing is nursing in

disasters. With the increasing use of weapons of terror and mass destruction,

the emergency nurse must expand his or her knowledge base to encompass

recognizing and treating patients exposed to biologic and other terror weapons

and anticipate nursing care in the event of a mass casualty inci-dent.

Documentation of Consent

Consent to examine and

treat the patient is part of the ED record. The patient must consent to

invasive procedures (eg, angiogra-phy, lumbar puncture) unless he or she is

unconscious or in crit-ical condition and unable to make decisions. If the

patient is unconscious and brought to the ED without family or friends, this

fact should be documented. Monitoring of the patient’s con-dition, as well as

all instituted treatments and the times at which they were performed, must be

documented. After treatment, a notation is made on the record about the

patient’s condition on discharge or transfer and about instructions given to

the patient and family for follow-up care.

Limiting Exposure to Health Risks

Because of the

increasing numbers of people infected with hep-atitis B and with human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV), health care providers are at an increased risk

for exposure to communi-cable diseases through blood or other body fluids. This

risk is fur-ther compounded in the ED because of the common use of invasive

treatments in addition to the wide range of patient con-ditions. All emergency

health care providers should adhere strictly to standard precautions for

minimizing exposure.

The reemergence of tuberculosis, a major health problem, is complicated by multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and by tubercu-losis concomitant with HIV infection. Early identification and adherence to transmission-based precautions for patients who are potentially infectious is crucial. Nurses in the ED are usually fitted with a personal high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA)-filter mask apparatus to use when treating patients with airborne diseases.

The potential for exposure to highly contagious

organisms, hazardous chemicals or gases, and radiation related to acts of

ter-rorism or natural or manmade disasters present additional risks to ED

staff.

Providing Holistic Care

Sudden illness or trauma

is a stress to physiologic and psycho-logical homeostasis that requires

physiologic and psychological healing. Patients and families experiencing

sudden injury or ill-ness often are overwhelmed by anxiety because they have

not had time to adapt to the crisis. They experience real and terrifying fear

of death, mutilation, immobilization, and other assaults on their personal

identity and body integrity. When confronted with trauma, severe disfigurement,

severe illness, or sudden death, the family experiences several stages of

crisis. The stages begin with anxiety and progress through denial, remorse and

guilt, anger, grief, and reconciliation. The initial goal for the patient and

family is anxiety reduction, a prerequisite to recovering the ability to cope.

Assessment of the patient and family’s psychological

function includes evaluating emotional expression, degree of anxiety, and

cognitive functioning. Possible nursing diagnoses include anxiety related to

uncertain potential outcomes of the illness or trauma and ineffective

individual coping related to acute situational crisis. In addition to anxiety,

possible nursing diagnoses for the family include anticipatory grieving and

alterations in family processes related to acute situational crises.

PATIENT-FOCUSED INTERVENTIONS

Those caring for the

patient should act confidently and compe-tently to relieve anxiety. Reacting

and responding to the patient in a warm manner promotes a sense of security.

Explanations should be given on a level that the patient can understand,

because an informed patient is better able to cope positively with stress.

Human contact and reassuring words reduce the panic of the se-verely injured

person and aid in dispelling fear of the unknown.

The unconscious patient

should be treated as if conscious. That is, the patient should be touched,

called by name, and given an ex-planation of every procedure that is performed.

As the patient re-gains consciousness, the nurse should orient the patient by

stating his or her name, the date, and the location. This basic information

should be provided repeatedly, as needed, in a reassuring way.

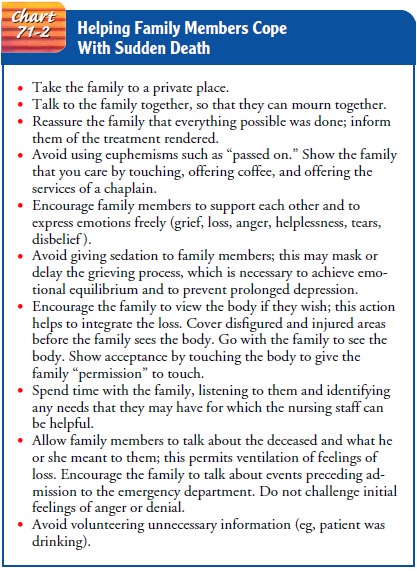

FAMILY-FOCUSED INTERVENTIONS

The family is kept

informed about where the patient is, how he or she is doing, and the care that

is being given. Allowing the family to stay with the patient, when possible,

also helps allay their anx-ieties. Additional interventions are based on the

assessment of the stage of crisis that the family is experiencing. Measures to

help fam-ily members cope with sudden death are presented in Chart 71-2.

Anxiety

and Denial.During these stages,

family members are en-couraged to recognize and talk about their feelings of

anxiety. Asking questions is encouraged. Honest answers given at the level of

the family’s understanding must be provided. Although denial is an ego-defense

mechanism that protects one from recognizing painful and disturbing aspects of

reality, prolonged denial is not encouraged or supported. The family must be

prepared for the reality of what has happened and what may come.

Remorse and Guilt.Expressions of remorse and guilt may beheard, with family members accusing themselves (or each other) of negligence or minor omissions. Family members are urged to verbalize their feelings until they realize that there was probably little that they could have done to prevent the injury or illness.

Anger.Expressions of anger, common in crisis situations, are away of handling

anxiety and fear. Anger is frequently directed at the patient, but it is also

often expressed toward the physician, the nurse, or admitting personnel. The

therapeutic approach is to allow the anger to be ventilated, then assist the

family to identify their feelings of frustration.

Grief.Grief is a complex emotional response to

anticipated or ac-tual loss. The key nursing intervention is to help family

members work through their grief and to support their coping mecha-nisms,

letting them know that it is normal and acceptable for them to cry, feel pain,

and express loss. The hospital chaplain and social services staff both serve as

invaluable members of the team when assisting families to work through their

grief.

EMERGENCY NURSING AND THE CONTINUUM OF CARE

As stated previously,

one principle underlying emergency care is that the patient will be rapidly

assessed, treated, and referred to the appropriate setting for ongoing care.

This makes the ED a very temporary point on the continuum of care. Most

patients who receive emergency care are discharged directly from the ED to

their homes, and emergency nurses must plan and facilitate the patient’s safe

discharge and follow-up care in the home and the community.

Discharge Planning

Before discharge, instructions for continuing care are

given to the patient and the family or significant others. All instructions

should be given not only verbally but also in writing, so that the patient can

refer to them later. Many EDs have preprinted stan-dard instruction sheets for

the more common conditions. These instructions are then individualized for each

patient. These in-structions may be available in a variety of languages. If

they are not available in the language that the patient needs, an inter-preter

should be used. Instructions should include information about prescribed

medications, treatments, diet, activity, and when to contact a health care

provider or schedule follow-up appointments. It is imperative that instructions

are written leg-ibly, use simple language, and are clear in their teaching.

When providing discharge instructions, the nurse also considers any special

needs the patient may have related to hearing or visual deficits.

Community Services

Before discharge, some patients require the services of a

social worker to help them meet continuing health care needs. For pa-tients and

families who cannot provide care at home, community agencies (eg, Home Care

Nursing Services, Visiting Nurse Asso-ciation) may be contacted before

discharge to arrange services. This is particularly important for elderly

patients who need assis-tance. Identifying continuing health care needs and

making arrangements for meeting these needs can prevent return visits to the ED

and readmission to the hospital.

For patients who are

returning to extended care facilities and for those who already rely on

community agencies for continu-ing health care, communication about the

patient’s condition and any changes in health care needs that have occurred

must be provided to the appropriate facilities or agencies. This commu-nication

is essential to promote continuity of care and to ensure ongoing care to meet

the patient’s changing health care needs.

Gerontologic Considerations

The ED is a common point of entry into the health care

system for patients 65 years of age and older. In fact, patients in this age

group account for more than 99 million visits to emergency fa-cilities each

year (see Chart 71-1). Elderly patients typically arrive with one or more

presenting conditions involving the skin, cardio-vascular system, or abdomen.

Nonspecific symptoms, such as weakness and fatigue, episodes of falling,

incontinence, and change in mental status, may be manifestations of acute,

poten-tially life-threatening illness in the elderly person. Emergencies in

this age group may be more difficult to manage because elderly patients may

have

·

An atypical presentation

·

An altered response to

treatment

·

A greater risk of developing

complications

The elderly patient may perceive the emergency as a

crisis sig-naling the end of an independent lifestyle or even resulting in

death. The nurse should give attention to the patient’s feelings of anxiety and

fear.

The older patient may have fewer sources of social and

finan-cial support in addition to frail health. The nurse should assess the

psychosocial resources of the patient (and of the caregiver, if necessary) and

anticipate discharge needs. Referrals for support services (eg, to the social

service department or a gerontologic nurse specialist) may be necessary.

Related Topics