Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Vascular Disorders and Problems of Peripheral Circulation

Venous Thrombosis, Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT), Thrombophlebitis, and Phlebothrombosis

Management of Venous Disorders

VENOUS

THROMBOSIS,DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS (DVT), THROMBOPHLEBITIS,AND PHLEBOTHROMBOSIS

Although

the terms venous thrombosis, deep vein thrombosis(DVT),

thrombophlebitis, and

phlebothrombosis do not necessarilyreflect identical disease processes, for

clinical purposes, they are often used interchangeably.

Pathophysiology

Superficial

veins, such as the greater saphenous, lesser saphenous, cephalic, basilic, and

external jugular veins, are thick-walled mus-cular structures that lie just

under the skin. Deep veins are thin walled and have less muscle in the media.

They run parallel to ar-teries and bear the same names as the arteries. Deep and

su-perficial veins have valves that permit unidirectional flow back to the

heart. The valves lie at the base of a segment of the vein that is expanded

into a sinus. This arrangement permits the valves to open without coming into

contact with the wall of the vein, per-mitting rapid closure when the blood

starts to flow backward. Other kinds of veins are known as perforating veins.

These vessels have valves that allow one-way blood flow from the superficial

system to the deep system.

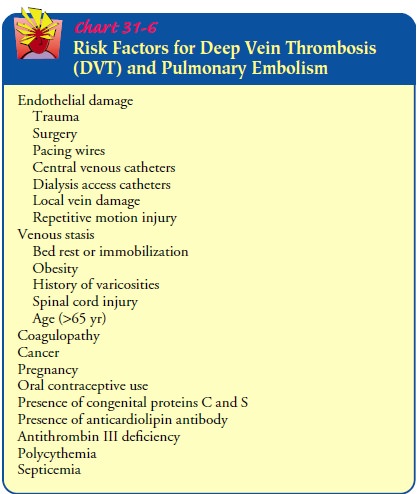

Although

the exact cause of venous thrombosis remains un-clear, three factors, known as

Virchow’s triad, are believed to play a significant role in its development:

stasis of blood (venous sta-sis), vessel wall injury, and altered blood

coagulation (Chart 31-6). At least two of the factors seem to be necessary for

thrombosis to occur. Venous stasis occurs when blood flow is reduced, as in

heart failure or shock; when veins are dilated, as with some med-ication

therapies; and when skeletal muscle contraction is reduced, as in immobility,

paralysis of the extremities, or anesthesia. Moreover, bed rest reduces blood

flow in the legs by at least 50%. Damage to the intimal lining of blood vessels

creates a site for clot formation. Direct trauma to the vessels, as with

fractures or dis-location, diseases of the veins, and chemical irritation of

the vein from intravenous medications or solutions, can damage veins.

In-creased blood coagulability occurs most commonly in patients who have been

abruptly withdrawn from anticoagulant medica-tions. Oral contraceptive use and

several blood dyscrasias (ab-normalities) also can lead to hypercoagulability.

Formation

of a thrombus frequently accompanies thrombo-phlebitis, which is an

inflammation of the vein walls. When a thrombus develops initially in the veins

as a result of stasis or hy-percoagulability but without inflammation, the

process is referred to as phlebothrombosis. Venous thrombosis can occur in any

vein but occurs more in the veins of the lower extremities. The superficial and

deep veins of the extremities may be affected.

Upper extremity venous thrombosis is not as common as lower extremity thrombosis. However, upper extremity venous throm-bosis is more common in patients with intravenous catheters or in patients with an underlying disease that causes hypercoagula-bility. Internal trauma to the vessels may result from pacemaker leads, chemotherapy ports, dialysis catheters, or parenteral nutrition lines.

The lumen of the vein may be decreased as a result of the catheter or

from external compression, such as by neoplasms or an extra cervical rib.

Effort thrombosis of the upper extremity is caused by repetitive motion, such

as experienced by competitive swimmers, tennis players, and construction workers,

that irritates the vessel wall, causing inflammation and subsequent thrombosis.

Venous

thrombi are aggregates of platelets attached to the vein wall, along with a

tail-like appendage containing fibrin, white blood cells, and many red blood

cells. The “tail” can grow or can propagate in the direction of blood flow as

successive layers of the thrombus form. A propagating venous thrombosis is

dangerous because parts of the thrombus can break off and produce an em-bolic

occlusion of the pulmonary blood vessels. Fragmentation of the thrombus can

occur spontaneously as it dissolves naturally, or it can occur in association

with an elevation in venous pressure, as occurs when a person stands suddenly

or engages in muscular activity after prolonged inactivity. After an episode of

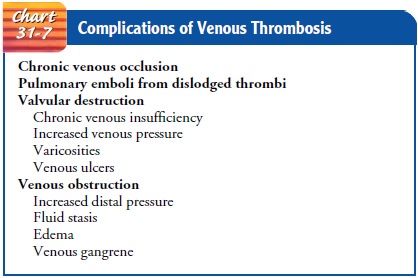

acute deep vein thrombosis, recanalization of the lumen typically occurs. The

time required for complete recanalization is an important de-terminant of

venous valvular incompetence, which is one com-plication of venous thrombosis

(Meissner et al., 2000). Other complications of venous thrombosis are listed in

Chart 31-7.

Clinical Manifestations

A

major problem associated with recognizing deep vein throm-bosis is that the

signs and symptoms are nonspecific. The excep-tion is phlegmasia cerulea dolens

(massive iliofemoral venous thrombosis), in which the entire extremity becomes

massively swollen, tense, painful, and cool to the touch. Despite this

vari-ability, clinical signs should always be investigated.

DEEP VEINS

With obstruction of the deep veins comes edema and swelling of the extremity because the outflow of venous blood is inhibited.

The

amount of swelling can be determined by measuring the cir-cumference of the

affected extremity at various levels with a tape measure and comparing one

extremity with the other at the same level to determine size differences. If

both extremities are swollen, a size difference may be difficult to detect. The

affected extremity may feel warmer than the unaffected extremity, and the

superficial veins may appear more prominent.

Tenderness,

which usually occurs later, is produced by in-flammation of the vein wall and

can be detected by gently pal-pating the affected extremity. Homans’ sign (pain

in the calf after the foot is sharply dorsiflexed) is not specific for deep

vein throm-bosis because it can be elicited in any painful condition of the

calf. In some cases, signs of a pulmonary embolus are the first indica-tion of

deep vein thrombosis.

SUPERFICIAL VEINS

Thrombosis

of superficial veins produces pain or tenderness, red-ness, and warmth in the

involved area. The risk of the superficial venous thrombi becoming dislodged or

fragmenting into emboli is very low because most of them dissolve

spontaneously. This condition can be treated at home with bed rest, elevation

of the leg, analgesics, and possibly anti-inflammatory medication.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Careful

assessment is invaluable in detecting early signs of venous disorders of the

lower extremities. Patients with a history of vari-cose veins,

hypercoagulation, neoplastic disease, cardiovascular disease, or recent major

surgery or injury are at high risk. Other patients at high risk include those

who are obese or elderly and women taking oral contraceptives.

When

performing the nursing assessment, key concerns in-clude limb pain, a feeling

of heaviness, functional impairment, ankle engorgement, and edema; differences

in leg circumference bilaterally from thigh to ankle; increase in the surface

tempera-ture of the leg, particularly the calf or ankle; and areas of

tender-ness or superficial thrombosis (ie, cordlike venous segment). Homans’

sign (pain in the calf as the foot is sharply dorsiflexed) has been used

historically to assess for DVT. It is not a reliable or valid sign for DVT and

has no clinical value in the assessment of a patient for DVT.

Prevention

Venous

thrombosis, thrombophlebitis, and DVT can be pre-vented, especially if patients

who are considered at high risk are identified and preventive measures are

instituted without delay.Preventive measures include the application of elastic

compres-sion stockings, the use of intermittent pneumatic compression devices,

and special body positioning and exercise (discussed later in the section on nursing

management). A further method to prevent venous thrombosis in surgical patients

is administration of subcutaneous unfractionated or low molecular weight

heparin.

Medical Management

The

objectives of treatment for deep vein thrombosis are to pre-vent the thrombus

from growing and fragmenting (risking pul-monary embolism) and to prevent

recurrent thromboemboli. Anticoagulant therapy (administration of a medication

to delay the clotting time of blood, prevent the formation of a thrombus in

postoperative patients, and forestall the extension of a throm-bus after it has

formed) can meet these objectives, although anti-coagulants cannot dissolve a

thrombus that has already formed.

ANTICOAGULATION THERAPY

Measures

for preventing or reducing blood clotting within the vascular system are

indicated in patients with thrombophlebitis, recurrent embolus formation, and

persistent leg edema from heart failure. They are also indicated in elderly

patients with a hip fracture that may result in lengthy immobilization.

Unfractionated Heparin.

Unfractionated

heparin (heparin) is ad-ministered subcutaneously to prevent development of

deep vein thrombosis, or by intermittent intravenous infusion or continuous

infusion for 5 to 7 days to prevent the extension of a thrombus and the

development of new thrombi. Oral anticoagulants, such as warfarin (Coumadin),

are administered with heparin therapy. Medication dosage is regulated by

monitoring the partial throm-boplastin time, the international normalized ratio (INR), and the platelet count.

Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin.

Subcutaneous

low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is an effective treatment for some cases of

deep vein thrombosis. It has a longer half-life than unfrac-tionated heparin,

so doses can be given in one or two subcuta-neous injections each day. Doses

are adjusted according to weight. LMWH prevents the extension of a thrombus and

development of new thrombi and is associated with fewer bleeding complica-tions

than unfractionated heparin. Because there are several prepa-rations, the

dosing schedule must be based on the product used and the protocol at each

institution. The cost is higher than for unfractionated heparin; however, LMWH

may be used safely in pregnant women, and the patients may be more mobile and

have an improved quality of life.

Thrombolytic Therapy.

Unlike the

heparins, thrombolytic (fibri-nolytic) therapy causes the thrombus to lyse and

dissolve in 50% of patients. Thrombolytic therapy (eg, tissue plasminogen

acti-vator [t-PA, alteplase, Activase], reteplase [r-PA, Retavase],

tenecteplase [TNKase], staphylokinase, urokinase, streptokinase) is given

within the first 3 days after acute thrombosis. Therapy initiated beyond 5 days

after the onset of symptoms is signifi-cantly less effective (Moore, 2002). The

advantages of throm-bolytic therapy include less long-term damage to the venous

valves and a reduced incidence of postthrombotic syndrome and chronic venous

insufficiency. However, thrombolytic therapy re-sults in approximately a

threefold greater incidence of bleeding than heparin. If bleeding occurs and

cannot be stopped, the thrombolytic agent is discontinued.

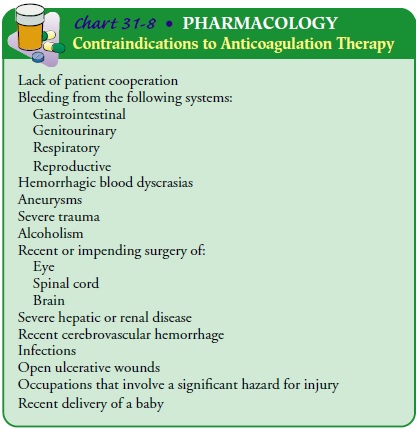

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgery

is necessary for deep vein thrombosis when anticoagulant or thrombolytic

therapy is contraindicated (Chart 31-8), the danger of pulmonary embolism is

extreme, or the venous drainage is so severely compromised that permanent

damage to the ex-tremity will probably result. A thrombectomy (removal of the

thrombosis) is the procedure of choice. A vena cava filter may be placed at the

time of the thrombectomy; this filter traps large emboli and prevents pulmonary

emboli.

Nursing Management

If the

patient is receiving anticoagulant therapy, the nurse must frequently monitor

the partial thromboplastin time, prothrom-bin time, hemoglobin and hematocrit

values, platelet count, and fibrinogen level. Close observation is also

required to detect bleeding; if bleeding occurs, it must be reported

immediately and anticoagulant therapy discontinued.

ASSESSING AND MONITORING ANTICOAGULANT THERAPY

To

prevent inadvertent infusion of large volumes of heparin, which could cause

hemorrhage, continuous intravenous infusion by electronic infusion device is

the preferred method of adminis-tering unfractionated heparin. Dosage

calculations are based on the patient’s weight, and any possible bleeding

tendencies are detected by a pretreatment clotting profile. If renal

insufficiency exists, lower doses of heparin are required. Periodic coagulation

tests and hematocrit levels are obtained. Heparin is in the effec-tive, or

therapeutic, range when the partial thromboplastin time is 1.5 times the

control.

Intermittent

intravenous injection is another means of ad-ministering heparin; a dilute

solution of heparin is administered every 4 hours. Administration may be

facilitated by using a hep-arin lock, an intravenous catheter or a small,

butterfly-type scalp vein needle with an injection site at the end of the

tubing.

Oral anticoagulants, such as warfarin, are monitored by the prothrombin time or INR. Because their effect is delayed for 3 to 5 days, they are usually administered with heparin until desired anticoagulation has been achieved (ie, when the prothrombin time is 1.5 to 2 times normal or the INR is 2.0 to 3.0).

MONITORING AND MANAGING POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Bleeding.

The principal complication of

anticoagulant therapyis spontaneous bleeding anywhere in the body. Bleeding

from the kidneys is detected by microscopic examination of the urine and is

often the first sign of anticoagulant toxicity from excessive dosage. Bruises,

nosebleeds, and bleeding gums are also early signs. To reverse the effects of

heparin promptly, intravenous injections of protamine sulfate may be

administered. Reversing the effects of warfarin, a coumarin derivative, is more

difficult, but effective measures that may be prescribed include vitamin K and

possibly transfusion of fresh frozen plasma.

Thrombocytopenia.

Another

complication of therapy may beheparin-induced thrombocytopenia (decrease in

platelets), which may develop in patients who receive heparin for more than 5

days or on readministration after a brief interruption of heparin therapy.

Beginning warfarin concomitantly with heparin can provide a stable INR or

prothrombin time by day 5 of heparin treatment.

The

use of LMWH is less frequently associated with heparin-induced

thrombocytopenia. The thrombocytopenia is thought to result from an immunologic

mechanism that causes aggregation of platelets. This serious complication

results in thromboembolic manifestations, and the prognosis is extremely

guarded.

Prevention

of thrombocytopenia depends on regular moni-toring of platelet counts. Early

signs of thrombocytopenia are a falling platelet count to less than 100,000/mL,

a decrease in platelet count exceeding 25% at one time, the need for increasing

doses of heparin to maintain the therapeutic level, thromboembolic or

hemorrhagic complications, and a history of heparin sensitivity (Stevens,

2000). If thrombocytopenia does occur, platelet aggre-gation studies are

conducted, the heparin is discontinued, and protamine sulfate is administered

to reverse heparin’s effects.

Drug Interactions.

Because oral

anticoagulants interact withmany other medications and herbal and nutritional

supplements, close monitoring of the patient’s medication schedule is

neces-sary. Medications and supplements that potentiate oral anticoag-ulants

include salicylates, anabolic steroids, chloral hydrate, glucagon,

chloramphenicol, neomycin, quinidine, phenylbuta-zone (Butazolidin), coenzyme

Q10, dong quai, garlic, gingko, ginseng, green tea, and vitamin E; those that

decrease the antico-agulant effect include phenytoin, barbiturates, diuretics,

estrogen, and vitamin C. It is advisable to identify medication interactions

for patients taking specific oral anticoagulants. Contraindications to

anticoagulant therapy are summarized in Chart 31-8.

PROVIDING COMFORT

Bed

rest, elevation of the affected extremity, elastic compression stockings, and

analgesics for pain relief are adjuncts to therapy. They help to improve

circulation and increase comfort. Depend-ing on the extent and location of a

venous thrombosis, bed rest may be required for 5 to 7 days after diagnosis.

This is approxi-mately the time necessary for the thrombus to adhere to the

vein wall, preventing embolization.

Warm,

moist packs applied to the affected extremity reduce the discomfort associated

with deep vein thrombosis, as do mild analgesics prescribed for pain control.

When the patient begins to ambulate, elastic compression stockings are used.

Walking is better than standing or sitting for long periods. Bed exercises,

such as dorsiflexion of the foot, are also recommended.

APPLYING ELASTIC COMPRESSION STOCKINGS

Elastic

compression stockings usually are prescribed for patients with venous

insufficiency. These stockings exert a sustained, evenly distributed pressure

over the entire surface of the calves, reducing the caliber of the superficial

veins in the legs and result-ing in increased flow in the deeper veins. The

stockings may be knee-high, thigh-high, or panty hose. Thigh-high stockings are

difficult for the patient to wear, because they have a tendency to roll down.

The roll of the stocking further restricts blood flow rather than the stocking

providing evenly distributed pressure over the thigh.

When

the stockings are off, the skin is inspected for signs of irritation, and the

calves are examined for possible tenderness. Any skin changes or signs of

tenderness are reported. Stockings are contraindicated in patients with severe

pitting edema because they can produce severe pitting at the knee.

Gerontologic Considerations

Because

of decreased strength and manual dexterity, elderly pa-tients may be unable to

apply elastic compression stockings prop-erly. If such is the case, a family

member or friend should be taught to assist the patient to apply the stockings

so that they do not cause undue pressure on any part of the feet or legs.

USING INTERMITTENT PNEUMATIC COMPRESSION DEVICES

These

devices can be used with elastic compression stockings to prevent deep vein

thrombosis. They consist of an electric con-troller that is attached by air

hoses to plastic knee-high or thigh-high sleeves. The leg sleeves are divided

into compartments, which sequentially fill to apply pressure to the ankle,

calf, and thigh at 35 to 55 mm Hg of pressure. These devices can increase blood

velocity beyond that produced by the stockings. Nursing measures include

ensuring that prescribed pressures are not exceeded and assessing for patient

comfort.

POSITIONING THE BODY AND ENCOURAGING EXERCISE

When

the patient is on bed rest, the feet and lower legs should be elevated

periodically above the level of the heart. This position al-lows the

superficial and tibial veins to empty rapidly and to re-main collapsed. Active

and passive leg exercises, particularly those involving calf muscles, should be

performed to increase venous flow. Early ambulation is most effective in

preventing venous sta-sis. Deep-breathing exercises are beneficial because they

produce increased negative pressure in the thorax, which assists in empty-ing

the large veins. Once ambulatory, patients are instructed to avoid sitting for

more than 2 hours at a time. The goal is to walk at least 10 minutes every 1 to

2 hours. Patients are also instructed to perform active and passive leg

exercises when they are not able to ambulate as frequently as necessary, such

as during long car, train, and plane trips.

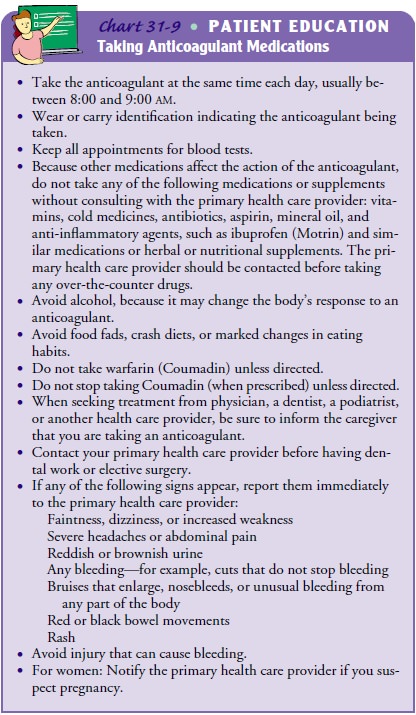

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

In

addition to teaching the patient how to apply elastic compres-sion stockings

and explaining the importance of elevating the legs and exercising adequately,

the nurse teaches about the medica-tion, its purpose, and the need to take the

correct amount at the specific times prescribed (Chart 31-9). The patient

should also be aware that blood tests are scheduled periodically to determine

whether a change in medication or dosage is required. If the pa-tient fails to

adhere to the therapeutic regimen, continuation of the medication therapy

should be questioned. A person who re-fuses to discontinue the use of alcohol

should not receive anti-coagulants because chronic alcohol use decreases their

effectiveness. In patients with liver problems, the potential for bleeding may

be exacerbated by anticoagulant therapy.

Related Topics