Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Vascular Disorders and Problems of Peripheral Circulation

Aortic Aneurysm

AORTIC

ANEURYSM

An

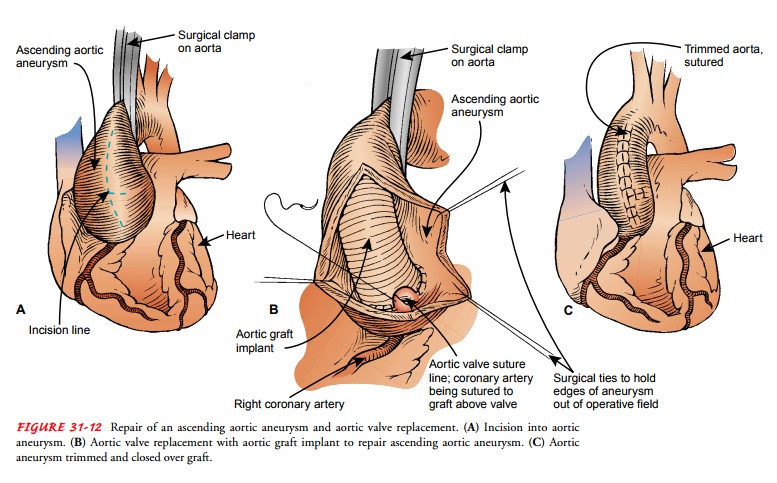

aneurysm is a localized sac or dilation formed at a weak point in the wall of

the aorta (Fig. 31-11). It may be classified by its shape or form. The most

common forms of aneurysms are sac-cular or fusiform. A saccular aneurysm

projects from one side of the vessel only. If an entire arterial segment

becomes dilated, a fusiform aneurysm develops. Very small aneurysms due to

local-ized infection are called mycotic aneurysms.

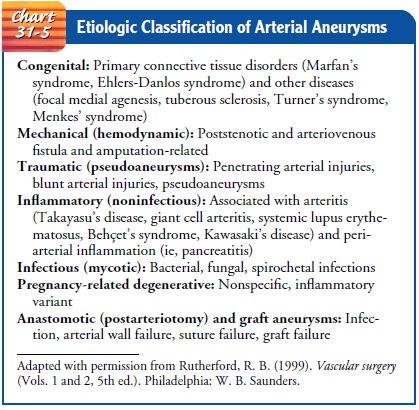

Historically,

the cause of abdominal aortic aneurysm, the most common type of degenerative

aneurysm, has been attributed to atherosclerotic changes in the aorta. Other

causes of aneurysm formation are listed in Chart 31-5. Aneurysms are serious

because they can rupture, leading to hemorrhage and death.

THORACIC AORTIC ANEURYSM

Approximately

85% of all cases of thoracic aortic aneurysm are caused by atherosclerosis.

They occur most frequently in men between the ages 40 and 70 years. The

thoracic area is the most common site for a dissecting aneurysm. About one

third of pa-tients with thoracic aneurysms die of rupture of the aneurysm

(Rutherford, 1999).

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms are variable and depend on how rapidly the aneurysm dilates and how the pulsating mass affects surrounding intratho-racic structures. Some patients are asymptomatic. In most cases, pain is the most prominent symptom. The pain is usually con-stant and boring but may occur only when the person is supine.

Other

conspicuous symptoms are dyspnea, the result of pressure of the sac against the

trachea, a main bronchus, or the lung itself; cough, frequently paroxysmal and

with a brassy quality; hoarseness, stridor, or weakness or complete loss of the

voice (aphonia), re-sulting from pressure against the left recurrent laryngeal

nerve; and dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing) due to impingement on the

esophagus by the aneurysm.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

When

large veins in the chest are compressed by the aneurysm, the superficial veins

of the chest, neck, or arms become dilated, and edematous areas on the chest

wall and cyanosis are often evident. Pressure against the cervical sympathetic

chain can result in unequal pupils. Diagnosis of a thoracic aortic aneurysm is

prin-cipally made by chest x-ray, transesophageal echocardiography, and CT.

Medical Management

In

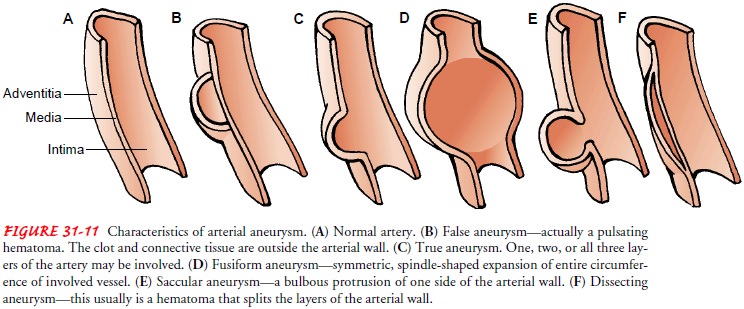

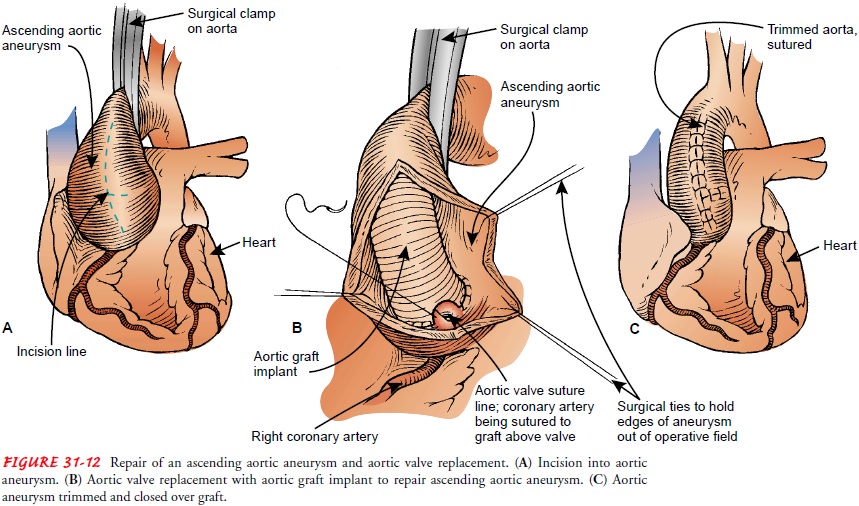

most cases, an aneurysm is treated by surgical repair. General measures such as

controlling blood pressure and correcting risk factors may be helpful. It is

important to control blood pressure in patients with dissecting aneurysms.

Systolic pressure is main-tained at about 100 to 120 mm Hg with

antihypertensive med-ications (eg, hydralazine hydrochloride [Hydralazine],

esmolol hydrochloride [Brevibloc] or another beta-blocker such as atenolol

[Tenormin] or timolol maleate [Timoptic]). Pulsatile flow is re-duced by

medications that reduce cardiac contractility (eg, propranolol [Inderal]). The

goal of surgery is to repair the aneurysm and restore vascular continuity with

a vascular graft (Fig. 31-12). Intensive monitoring is usually required after

this type of surgery, and the patient is cared for in the critical care unit.

Repair of thoracic aneurysms using endovascular grafts implanted (de-ployed) percutaneously

in an interventional laboratory (eg, cardiac catheterization laboratory) may

decrease postoperative recovery time and decrease complications compared with

traditional sur-gical techniques.

ABDOMINAL AORTIC ANEURYSM

The

most common cause of abdominal aortic aneurysm is athero-sclerosis. The

condition, which is more common among Cau-casians, affects men four times more

often than women and is most prevalent in elderly patients (Rutherford, 1999).

Most of these aneurysms occur below the renal arteries (infrarenal aneurysms).

Untreated, the eventual outcome may be rupture and death.

Pathophysiology

All aneurysms involve a damaged media layer of the vessel. This may be caused by congenital weakness, trauma, or disease. After an aneurysm develops, it tends to enlarge. Risk factors include ge-netic predisposition, smoking (or other tobacco use), and hyper-tension; more than one half of patients with aneurysms have hypertension.

Clinical Manifestations

About

two fifths of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms have symptoms; the

remainder do not. Some patients complain that they can feel their heart beating

in their abdomen when lying down, or they may say they feel an abdominal mass

or abdomi-nal throbbing. If the abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with

thrombus, a major vessel may be occluded or smaller distal occlusions may

result from emboli. A small cholesterol, platelet, or fibrin emboli may lodge

in the interosseous or digital arteries, causing blue toes.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

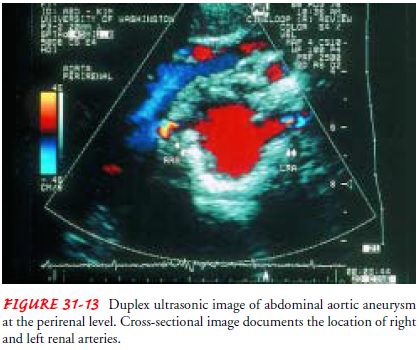

The

most important diagnostic indication of an abdominal aortic aneurysm is a

pulsatile mass in the middle and upper abdomen. About 80% of these aneurysms

can be palpated. A systolic bruit may be heard over the mass. Duplex

ultrasonography or CT is used to determine the size, length, and location of

the aneurysm (Fig. 31-13). When the aneurysm is small, ultrasonography is

conducted at 6-month intervals until the aneurysm reaches a size at which

surgery to prevent rupture is of more benefit than the possible complications

of a surgical procedure. Some aneurysms remain stable over many years of

observation.

Gerontologic Considerations

Most

abdominal aneurysms occur in patients between the ages of 60 and 90 years. Rupture

is likely with coexisting hypertension and with aneurysms wider than 6 cm. In

most cases at this point, the chances of rupture are greater than the chance of

death during surgical repair. If the elderly patient is considered at moderate

risk for complications related to surgery or anesthesia, the aneurysm is not

repaired until it is at least 5 cm (2 inches) wide.

Medical Management

An

expanding or enlarging abdominal aneurysm is likely to rupture. Surgery is the

treatment of choice for abdominal aneurysms wider than 5 cm (2 inches) wide or

those that are enlarging.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The standard treatment for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair has been open surgical repair of the aneurysm by resecting the vessel and sewing

a bypass graft in place. The mortality rate associated with elective aneurysm

repair, a major surgical procedure, is re-ported to be 1% to 4%. The prognosis

for a patient with a rup-tured aneurysm is poor, and surgery is performed

immediately (Rutherford, 1999).

An

alternative for treating an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneu-rysm is

endovascular grafting. Endovascular grafting involves the transluminal

placement and attachment of a sutureless aortic graft prosthesis across an

aneurysm (Fig. 31-14). This procedure can be performed under local or regional

anesthesia. Endovascular graft-ing of abdominal aortic aneurysms may be

performed if the patient’s abdominal aorta and iliac arteries are not extremely

tor-tuous and if the aneurysm does not begin at the level of the renal

arteries. Clinical trials are evaluating endograft treatment of ab-dominal

aortic aneurysms at or above the level of the renal arteries and the thoracic

aorta. Potential complications include bleeding, hematoma, or wound infection at

the femoral insertion site; distal ischemia or embolization; dissection or

perforation of the aorta; graft thrombosis; graft infection; break of the

attachment system; graft migration; proximal or distal graft leaks; delayed

rupture; and bowel ischemia.

Nursing Management

Before

surgery, nursing assessment is guided by anticipating a rupture and by

recognizing that the patient may have cardiovas-cular, cerebral, pulmonary, and

renal impairment from athero-sclerosis. The functional capacity of all organ systems

should be assessed. Medical therapies designed to stabilize physiologic

func-tion should be promptly implemented.

Signs

of impending rupture include severe back pain or ab-dominal pain, which may be

persistent or intermittent and is oftenlocalized in the middle or lower abdomen

to the left of the midline. Low back pain may also be present because of

pressure of the aneurysm on the lumbar nerves. This is a serious symptom,

usually indicating that the aneurysm is expanding rapidly and is about to rupture.

Indications of a rupturing abdominal aortic aneurysm in-clude constant, intense

back pain; falling blood pressure; and de-creasing hematocrit. Rupture into the

peritoneal cavity is rapidly fatal. A retroperitoneal rupture of an aneurysm

may result in hematomas in the scrotum, perineum, flank, or penis. Signs of

heart failure or a loud bruit may suggest a rupture into the vena cava. Rupture

into the vena cava results in the higher-pressure ar-terial blood entering the

lower-pressure venous system and causing turbulence, which is heard as a bruit.

The high blood pressure and increased blood volume returning to the right heart

from the vena cava may cause the right heart to fail. The overall surgical

mortal-ity rate associated with a ruptured aneurysm is 50% to 75%.

Postoperative

care requires intense monitoring of pulmonary, cardiovascular, renal, and

neurologic status. Possible complica-tions of surgery include arterial

occlusion, hemorrhage, infection, ischemic bowel, renal failure, and impotence.

Related Topics