Chapter: Psychology: Learning

Varieties of Learning

VARIETIES OF LEARNING

Overall, the attempt to find

general principles of learning—principles that apply to virtually all

species—has been rather successful. This is why we can gain insights into human

depression by studying helplessness in dogs, and it’s how we’ve increased our

understanding of human drug addiction—thanks to research on clas-sical

conditioning in rats. Other examples of learning phenomena shared across

species are easy to find.

We need to acknowledge, though,

that there are also important differences from one species to the next in how

learning proceeds. These differences are often best understood by taking a

biological perspective on learning—a perspective that highlights the actual function of learning in each species’

natural environment (see, for example, Bolles &Beecher, 1988; Domjan, 2005;

Rozin & Schull, 1988).

Biological Influences on Learning: Belongingness

In the early days of learning

theory, investigators widely believed that animals (both humans and others) are

capable of connecting any CS to any US in classical condition-ing, and of

associating virtually any response with any reinforcer in instrumental

con-ditioning. A child could be taught that a tone signaled the approach of

dinner or that a flashing light or a particular word did. Likewise, a rat could

be trained to press a lever to get food, water, or access to a sexually

receptive mate.

But a great deal of evidence speaks against this idea; instead, each species seems pre-disposed to form some associations and not others. The predispositions put biologicalconstraints on that species’ learning, governing what the species can learn easily andwhat it can learn only with difficulty. These associative predispositions are probably hardwired and likely to be a direct product of our evolutionary past (Rozin & Kalat, 1971, 1972; Seligman & Hager, 1972).

TASTE AVERSION LEARNING

A central example of the

biological constraints on learning comes from studies of tasteaversion learning. These studies make it clear that, from the

organism’s viewpoint, somestimuli belong together and some do not (Domjan,

1983, 2005; Garcia & Koelling, 1966).

To understand this phenomenon, we

need to begin with the fact that when a wild rat encounters a novel food, it

generally takes only a small bite at first. If the rat suffers no ill effects

from this first taste, it will return (perhaps a day or two later) for a second

helping and will gradually make the food a part of its regular diet. But what

if this novel food is harmful, either because of some natural toxin or an

exterminator’s poison? In that case, the initial taste will make the rat sick;

but because it ate only a little of the food, the rat will probably recover.

Based on this experience, though, the rat is likely to develop a strong

aversion to that particular flavor, so it never returns for a second dose of

the poison.

This sort of learning is easily

documented in the laboratory. The subjects, usually rats, are presented with a

food or drink that has a novel flavor—perhaps water with some vanilla added.

After drinking this flavored water, the rats are exposed to X-ray radiation—not

enough to injure them, but enough to make them ill. After they recover, the

rats show a strong aversion to the taste of vanilla and refuse to drink water

flavored in this way (Figure 7.30).

This learned taste aversion is

actually based on classical conditioning. The flavor (here, vanilla) serves as

the CS, and the sensation of being sick serves as the US. This is, however, a

specialized type of classical conditioning that is distinct from other forms in

the sheer speed of learning: One pairing of a taste + illness is all it takes

to establish the connection between them. This one-trial learning is obviously much faster than the speed of

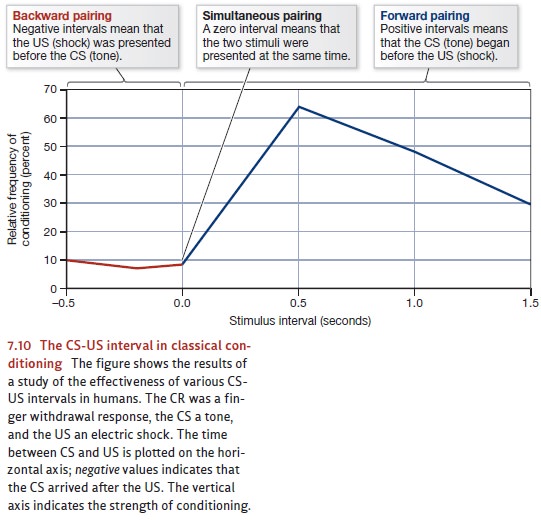

ordinary classical conditioning. What’s more, this form of condi-tioning is

distinctive in its timing requirements. In most classical conditioning, the CS

must be soon followed by the US; if too much time passes between these two

stim-uli, the likelihood of conditioning is much reduced (see Figure 7.10). In

taste aversion learning, in contrast, conditioning can be observed even if several

hours elapse between the CS and the US.

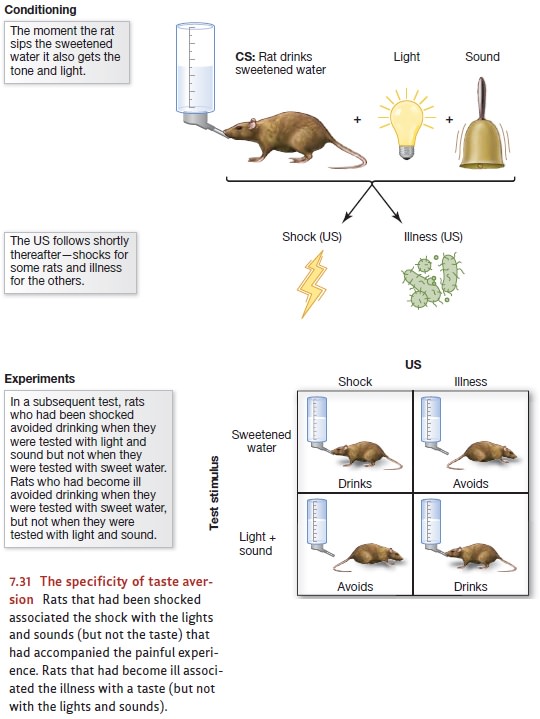

Learned taste aversions are also

remarkable for their specificity. In one early study, thirsty rats were allowed

to drink sweetened water through a tube. Whenever the rats licked the nozzle of

this tube, a bright light flashed and a loud clicking noise sounded. Thus, the

sweetness, bright light, and loud noise were always grouped together; if one

was presented, all were presented. One group of these rats then received an

electric shock to the feet. A second group was exposed to a dose of X-rays

strong enough to cause illness.

Notice, then, that we have two

different USs—illness for one group and foot shock for the other. Both groups

also have received a three-part CS: sweet + bright + noisy. The question is:

How will the animals put these pieces together—what will get associ-ated with

what?

To find out, the experimenters

tested the rats in a new situation. They gave some of the rats sweetened water,

unaccompanied by either light or noise. Rats that had received foot shock

showed no inclination to avoid this water; apparently, they didn’t associate

foot shock with the sweet flavor. However, rats that had been made ill with

X-rays refused to drink this sweetened water; they associated their illness

with the taste (Figure 7.31).

Another group of rats were tested

with unflavored water accompanied by the light and sound cues that were present

during training. Now the pattern was reversed. Rats that had become ill showed

no objection to this water. For them, the objectionable (sweet) taste was

absent from this test stimulus, and they didn’t associate their illness with

the sights and sounds that were present during the test. However, rats that had

been shocked earlier refused to drink this water; in their minds, pain was associated

with bright lights and loud clicks (Garcia & Koelling, 1966).

For the rat, therefore, taste

goes with illness, and sights and sounds go with exter-nally induced pain. And

for this species, this pattern makes biological sense. Illness in wild rats is

likely to have been caused by harmful or tainted food, and rats generally

select their food largely on the basis of flavor. So there’s survival value in

the rats being able to learn quickly about the connection between a particular

flavor and illness; this will provide useful information for them as they

select their next meal, ensuring that they don’t resample the harmful berries

or poisoned meat.

Using this logic, one might

expect species that choose foods on the basis of other attributes to make

different associations. For example, many birds make their food choices from a

distance, relying on the food’s visual appearance. How will this behavior

affect the data? In one study, quail were given blue, sour water to drink and

were then given a low dose of poison—enough to make them ill, but not enough to

harm them. Some of the birds were later tested with blue, unflavored water;

others were tested with water that was sour but colorless. The results showed

that the quail had developed a strong aversion to blue water but no aversion to

the sour water. They learned which water was safe based on its color rather

than its taste (Wilcoxin, Dragoin, & Kral, 1971).

Clearly, what belongs with what

depends upon the species. Birds are predisposed to associate illness with

visual cues. Rats (and many other mammals) associate illness with taste. In

each case, the bias makes the animal more prepared to form certain

asso-ciations and far less prepared to form others (Seligman, 1970).

We should also mention that taste

aversion learning, as important as it is, is just one example of prepared learning (Figure 7.32). We

mentioned a different example in the Prologue: Humans in one experiment were

shown specific pictures as the CS and received electric shocks as the US. When

the pictures showed flowers or mushrooms, learning was relatively slow. When the

pictures showed snakes, learning was much quicker. The impli-cation is that

humans (and many other primates) are innately prepared to associate the sight

of a snake with unpleasant or even painful experiences (Ă–hman & Mineka,

2003; Ă–hman & Soares, 1993; also Domjan, Cusato, & Krause, 2004).

These results may help us

understand why so many people are afraid of snakes and why strong phobias for

snakes are relatively common. Perhaps it’s not surprising that many cultures

regard snakes as the embodiments of evil. All these facts may simply be the

result of prepared learning in our species—our innate tendencies toward making

certain associations but not others.

BIOLOGICAL CONSTRAINTS ON INSTRUMENTAL CONDITIONING

Prepared learning can also be

demonstrated in instrumental conditioning because, from an animal’s viewpoint,

certain responses belong with some rewards and not oth-ers (Shettleworth,

1972). For example, pigeons can easily be taught to peck a lit key to obtain

food or water, but it’s extremely difficult to train a pigeon to peck in order

to escape electric shock (Hineline & Rachlin, 1969). In contrast, pigeons

can easily be taught to hop or flap their wings to get away from shock, but

it’s difficult to train the pigeon to produce these same responses in order to

gain food or water.

Once again, this pattern makes

good biological sense. The pigeon’s normal reaction to danger is to hop away or

break into flight, so the pigeon is biologically prepared to associate these

responses with aversive stimuli such as electrical shock. Pecking, in

con-trast, is not part of the pigeon’s innate defense pattern, so it’s

difficult for the pigeon to learn pecking as an escape response (Bolles, 1970).

Conversely, since pecking is what pigeons do naturally when they eat, the pigeon

is biologically prepared to associate this response with food or drink; it’s no

wonder, then, that pigeons easily learn to make this association in the

psychologist’s laboratory.

Different Types of Learning

It seems therefore that we need

to “tune” the laws of learning on a case-by-case basis to accommodate the fact

that a given species learns some relationships easily, others only with

difficulty, and still others not at all. This tuning builds some flexibility

into the laws of learning; but it allows us to retain the idea that there are general laws, appli-cable (with the

appropriate tuning) to all species and to all situations. Other evidence

suggests, though, that we must go further than this, because some types of

learning follow their own specialized rules and depend on specialized

capacities found in that species and few others. On this basis, we need to do

more than adjust the laws of learn-ing. We may also need some entirely new

laws—laws that are specific to the species that does the learning and to what’s

being learned (Gallistel, 1990; Roper, 1983).

As one example, consider the

Clark’s nutcracker, a bird that makes its home in the American Southwest

(Figure 7.33). In the summer, this bird buries thousands of pine nuts in

various hiding places over an area of several square miles. Then, throughout

the winter and early spring, the nutcracker flies back again and again to dig

up its thou-sands of caches. The bird doesn’t mark its cache sites in any

special way. Instead, it relies on memory to find its stash—a remarkable feat

that few of us could duplicate.

The Clark’s nutcracker has

various anatomical features that support its food-hoarding activities—for

example, there’s a special pouch under its tongue that it fills with pine nuts

when flying to find a hiding place. The bird’s extraordinary ability to learn a

huge number of geographical locations, and then to remember these locations for

the next few months, is probably a similar evolutionary adaptation. Like the

tongue pouch, this learning ability is a specialty of this species: Related

birds like jays and crows don’t store food in this way; and, when tested, they

have a correspondingly poorer spa-tial memory (D. Olson, 1991; Shettleworth,

1983, 1984, 1990).

Many phenomena of animal learning—in

birds, fish, and mammals—reveal similar specializations. In each case, the

organism has some extraordinary ability not shared even by closely related

species. In each case, the ability has obvious survival value and seems quite

narrow. The Clark’s nutcracker, for example, has no special skill in

remem-bering pictures or shapes; instead, its remarkable memory comes into play

only in the appropriate setting—when hiding and then relocating buried pine

nuts. Similarly, many birds show remarkable talent in learning the particular

songs used by their species. This skill, however, can be used for no other

purpose: A zebra finch easily mas-ters the notes of the zebra finch’s song but

is utterly inept at learning any other (non-musical) sequence of similar length

and complexity. Truly, then, these are specialized learning abilities—only one

or a few species have them, and they apply only to a partic-ular task crucial

for their members’ survival (Gallistel, 1990; Marler, 1970).

But what about humans? We’ve

emphasized that a great deal of human behavior—just like the behavior of every

animal species—is governed by principles of habituation as well as classical

and operant conditioning. But, even so, some of our behavior is the product of

distinctly human forms of learning. One exam-ple involves the processes through

which humans learn language. These processes seem controlled by innate

mechanisms that guide the learning and make it possible for us to achieve

remarkable linguistic competence by the time we’re 3 years old. Humans also

have remarkable inferen-tial abilities that allow us to gain broad sets of new

beliefs, based on events we’ve observed or information we’ve received from

others; and these new beliefs can pro-foundly affect our behavior.

Similarities in How Different Species Learn

In short, there are certainly

differences—as well as crucial similarities—in how species learn, and, as we’ve

noted, the differences make good biological sense. After all, each species

lives in its own distinctive environment and needs its own set of skills, and

so it may need to learn in its own ways. But what about the similarities? After

all, the rats and pigeons we study in the laboratory don’t gather food the way

a human does. They don’t communicate with their fellows the way a human does.

Their nervous systems are much simpler than ours. It wouldn’t be surprising,

therefore, if they learned in different ways than we do. Yet, as we’ve

repeatedly noted, the major phenomena of both classical and instrumental

conditioning apply across species— whether we’re considering humans, rats,

pigeons, cats, dogs, fish, or even some types of snails (Couvillon &

Bitterman, 1980; E. Kandel, 2007).

How should we think about this

point? Why do such diverse creatures share certain types of learning? The

answer lies in the fact that all of these creatures, no matter what their

evolutionary history or ecological niche, share certain needs. For example,

virtu-ally all creatures are better off if they can prepare themselves for

upcoming events, and to do this they need some way of anticipating what will

happen to them in the near future. It’s no wonder, then, that many species have

developed nervous systems that support classical conditioning.

Similarly, in the world we all

inhabit, important outcomes are often influenced by one’s behavior, so it pays

for all species to repeat actions that have worked well in the past and to

abandon actions that haven’t succeeded. Hence we might expect natural selection

to have favored organisms capable of learning about the consequences of their

actions and able to adjust their future behavior accordingly. In other words,

we’d expect natural selection to have favored organisms capable of instrumental

conditioning.

Of course, people are different

from pigeons, and pigeons from sea slugs; no one is questioning these points.

Even so, it seems that there are some types of learning that all species need

to do.

Related Topics