Chapter: Psychology: Learning

Habituation

HABITUATION

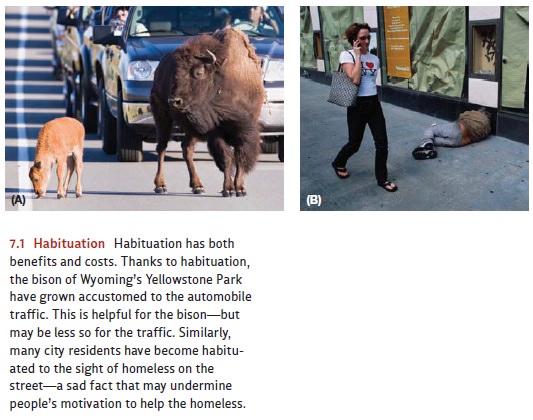

Perhaps the simplest form of

learning is habituationŌĆöthe decline

in an organismŌĆÖs response to a stimulus once the stimulus has become familiar.

As a concrete case, imag-ine someone living in an apartment on a busy street.

At first, he finds the traffic noises distracting and obnoxious. After heŌĆÖs

lived in the apartment for a while, though, the noises bother him much lessŌĆöand

eventually he doesnŌĆÖt notice them at all. At this point, heŌĆÖs become habituated

to the noises (Figure 7.1).

For the city dweller, habituation

is obviously important. (Otherwise, with the traffic noise as it is, these

people might never get any sleep!) But, more broadly, habituation produces a

huge benefit: We want to pay attention to unfamiliar stimuli, because these may

signal danger or indicate some unexpected opportunity. But, at the same time,

we donŌĆÖt want to waste time scrutinizing every stimulus we run across. How,

therefore, do we manage to be suitably selective? The answer is habituation;

this simple form of learning essentially guarantees that we ignore inputs weŌĆÖre

already familiar with and have found to be inconsequential, and focus instead

on the novel ones.

Just as important as habituation is its opposite: dishabituationŌĆöan increase in responding, caused by a change in something familiar. Thus, the city dweller whoŌĆÖs seemingly oblivious to traffic noise will notice if the noise suddenly stops. Likewise, imagine an office worker who has finally gotten used to the humming of the buildingŌĆÖs light fixtures. Despite her apparent success in ignoring this humming, sheŌĆÖs likely to notice immediately when, on one remarkable day, the humming ceases.

Dishabituation is obviously

important because a change in stimulation often brings important news about the

world. If the birds in the nearby trees suddenly stop chirping, is it because

theyŌĆÖve detected a predator? If so, the deer grazing in the meadow want to know

about this. If the sound of the brook abruptly grows louder, has the water

level suddenly increased? This, too, is certainly worth investigating. Thus,

dishabituation serves the function of calling attention to newly arrivingŌĆöand

potentially usefulŌĆöinformation, just as habituation serves the function of helping

you ignore old news.

These simple forms of learning

also provide powerful research tools

for investiga-tors. As one example, consider that adult speakers of Japanese

have trouble hearing the distinction, obvious to English speakers, between the

words red and led. This is because thereŌĆÖs no equivalent distinction between

these sounds in the Japanese lan-guage. But how did this perceptual difference

between English and Japanese speak-ers come to be? In one experiment,

4-month-old Japanese infants heard the sound ŌĆ£la, la, laŌĆØ repeated over and

over. At first this sound stream caught their attention, but they soon

habituated and stopped responding to the sounds. Then the researcher changed

the sound to repetitions of ŌĆ£ra, ra, ra.ŌĆØ Would the infants notice the change?

In fact, they did: The infants showed immediate dishabituation and once again

oriented to the sound. Apparently, Japanese infants heard the distinction

between these sounds as readily as infants in English-speaking countries did.

This seems, therefore, to be a case of ŌĆ£use it or lose itŌĆØ: All infants, no

matter where theyŌĆÖre born, can hear this acoustic difference. However, if the

sound difference is not rele-vant to the language in the infantŌĆÖs surroundings

(as, for example, in the case of Japanese), the infants stop paying attention

to the distinction. By the time theyŌĆÖre 12 months old, theyŌĆÖve completely lost

the ability to tell these sounds apart. This is on its own an important

finding, one that sheds light on how perception can change as a result of

experience and helps us under-stand one aspect of language learning. But, for

our purposes here, notice that this research relies on habituation and

dishabituation as a means of finding out what sounds different to an infant and what sounds the same. Thus, these simple phenom-ena of learning provide a

straightforward way to explore the perceptual capabilities of a very young

(preverbal) child.

Related Topics