Chapter: Psychology: Learning

Instrumental Conditioning: Thorndike and the Law of Effect

Thorndike and the Law of Effect

The experimental study of

instrumental conditioning began a century ago and was sparked by the debate

over Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Supporters of Darwin’s

theory emphasized the continuity among species, both living and extinct:

Despite their apparent differences, a bird’s wing, a whale’s fin, and a human

arm, for example, all have the same basic bone structure; this similarity makes

it plausi-ble that these diverse organisms all descended, by a series of

incremental steps, from common ancestors. But opponents of Darwin’s theory

pointed to something they per-ceived as the crucial discontinuity among

species: the human ability to think and reason—an ability they claimed animals

did not share. Didn’t this ability, unique to our species, require an

altogether different (non-Darwinian) type of explanation?

In response, Darwin and his

colleagues argued that there is, in fact, considerable continuity of mental

prowess across the animal kingdom. Yes, humans are smarter in some ways than

other species; but the differences might be smaller than they initially

seem. In support of this idea,

Darwinian naturalists collected stories about the intellec-tual achievements of

various animals (Darwin, 1871). These stories painted a flattering picture, as

in the reports of cunning cats that scattered breadcrumbs on the lawn to lure

birds into their reach (Romanes, 1882). In many cases, however, it was hard to

tell whether these reports were genuine or just bits of folklore. Even if they

were genuine, it was unclear whether the reports had been polished by the

loving touch of a proud pet owner. What was needed, therefore, was more

objective and better documented research—research that was made possible by a

method described in 1898 by Edward L. Thorndike (1874–1949; Figure 7.16).

CATS IN APUZZLE BOX

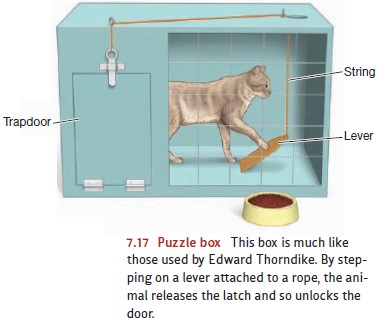

Thorndike’s method was to set up

a problem for an animal to solve. In his classic exper-iments, he placed a

hungry cat inside a box with a latched door. The cat could open the door—and

escape from the box—only by performing some simple action such as pulling a

loop of wire or pressing a lever (Figure 7.17); and once outside the box, the

cat was rewarded with a small portion of food. Then the cat was placed back

into the box for another trial so that the procedure could be repeated over and

over until the task of escaping the box was mastered.

On the first trial, the cats had

no notion of how to escape—and so they meowed loudly and clawed and bit at

their surroundings. This continued for several minutes until finally, purely by

accident, the animal hit upon the correct response.

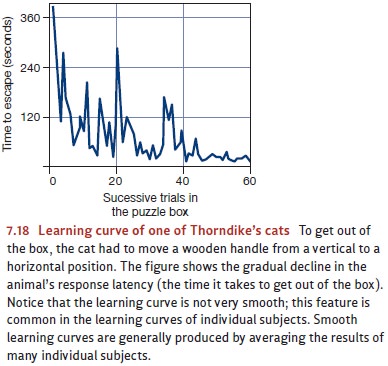

Subsequent trials brought gradual

improvement, and the animal took less and less time to produce the response

that unlocked the door. By the time the train-ing sessions were completed, the

cats’ behavior was almost unrecognizable from what it had been at the start.

When placed in the box, they immediately approached the wire loop or the lever,

yanked it or pressed it with businesslike dispatch, and hurried through the

open door to enjoy the well-deserved reward.

If you observed only the final

performance of these cats, you might well credit the animals with reason or

understanding. But Thorndike argued that the cats solved the problem in a very

different way. As proof, he recorded how much time the cats required on each trial

to escape from the puzzle box, and he charted how these times changed over the

course of learning. Thorndike found that the resulting curves declined quite

gradually as the learning proceeded (Figure 7.18). This isn’t the pattern we

would expect if the cats had achieved some understanding of how to solve the

problem. If they had, their curves would show a sud-den drop at some point in

the training, when they finally got the point. (“Aha!” mut-tered the insightful

cat, “it’s the lever that lets me out,” and henceforth howled and bit

no more.) Instead, these learning

curves suggest that the cats learned to escape in small increments; they

displayed no evidence at all of understanding and certainly no evi-dence of any

sudden insight into the problem’s solution.

THE LAW OF EFFECT

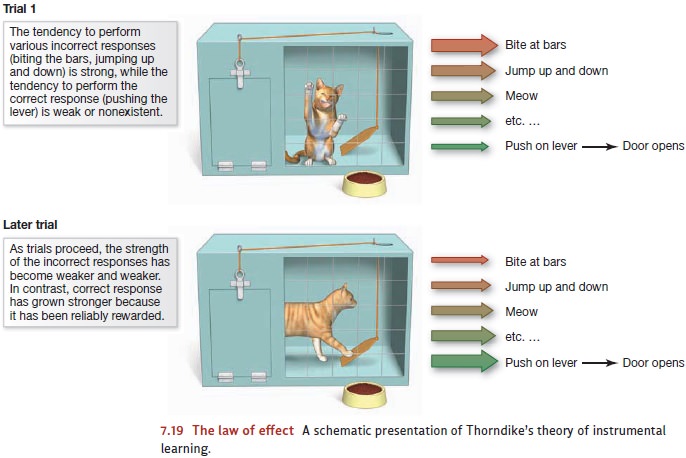

In Thorndike’s procedure, the

cats’ initial responses in the puzzle box—biting at the latch, clawing at the

walls—all led to failure. As the trials proceeded, though, the cats’ tendency

to produce these responses gradually weakened. At the same time, the animals’

tendency to produce the correct response was weak at first; but, over the

trials, this response gradually grew stronger. In Thorndike’s terms, the

correct response was gradually “stamped in,” while futile ones were “stamped

out.”

But what causes this stamping in

or stamping out? Thorndike’s answer was the lawof effect. Its key proposition is that if a response is followed

by a reward, that responsewill be strengthened. If a response is followed by no

reward (or, worse yet, by punish-ment), it will be weakened. In general, the

strength of a response is adjusted according to the response’s consequences

(Figure 7.19). In this view, we do not need to suppose that the cat’s

performance required any sophisticated intellectual processes. We likewise do

not need to assume that the animal noticed a connection between its acts and

the consequences of those acts. All we need to assert is that, if the animal

made a response and a reward followed soon after, that response was more likely

to be performed later.

Notice that Thorndike’s proposal

suggests a clear parallel between how an organism learns during its lifetime

and how species evolve, thanks to the forces of natural selection. In both

cases, variations that “work”—behaviors that lead to successful outcomes, or

individuals with successful adaptations—are kept on. In both cases, variations

that are less successful are weakened or dropped. And, crucially, in both cases

the selection involves no guide

or supervisor to steer the process forward. Instead, selection depends only on

the consequences of actions or adaptations and on whether these serve the organism’s

biological needs or not.

Related Topics