Chapter: Psychology: Learning

Instrumental Conditioning: The Major Phenomena of Instrumental Conditioning

The Major

Phenomena of Instrumental Conditioning

As Skinner noted, classical and

instrumental conditioning are different in impor-tant ways: Classical

conditioning builds on a response (UR) that’s automatically triggered by a

stimulus (US); instrumental conditioning involves behaviors that appear to be

voluntary. Classical conditioning involves learning about the relation between

two stimuli (US and CS); instrumental conditioning involves learning about the

relation between a response and a stimulus (the operant and a reward). Even

with these differences, modern theorists have argued that the two forms of

conditioning have a lot in common. This makes sense because both involve

learning about relationships among

simple events (stimuli or responses).

It’s perhaps inevitable, then, that many of the central phenomena of instrumental learning parallel those of classical conditioning. For example, in classical conditioning, learning trials typically involve the presentation of a CS followed by a US. In instrumental conditioning, learning trials typically involve a response by the organ-ism followed by a reward or reinforcer. The reinforcement often involves the presenta-tion of something good, such as grain to a hungry pigeon. Alternatively, reinforcement may involve the termination or prevention of something bad, such as the cessation of a loud noise.

In both forms of conditioning,

the more such pairings there are, the stronger the learning. And if we discontinue

these pairings so that the CS is no longer followed by the US or the response

by a reinforcer, the result is extinction.

GENERALIZATION AND DISCRIMINATION

An instrumental response is not

directly triggered by an external stimulus, the way a CR or UR is. But that

doesn’t mean external stimuli have no role here. In instrumental con-ditioning,

external events serve as discriminative

stimuli, signaling for an animal what sorts of behaviors will be rewarded

in a given situation. For example, suppose a pigeon is trained to hop onto a

platform to get some grain. When a green light is on, hopping on the platform

pays off. But when a red light is on, hopping gains no reward. Under these

circumstances, the green light becomes a positive discriminative stimulus and

the red light a negative one (usually labeled S+ and S–,

respectively). The pigeon swiftly learns this pattern and so will hop in the

presence of the first and not in the presence of the second.

Other examples are easy to find.

A child learns that pinching her sister leads to pun-ishment when her parents

are on the scene but may have no consequences otherwise. In this situation, the

child may learn to behave well in the presence of the S+ (i.e., when

her parents are there) but not in other circumstances. A hypochondriac may

learn that loud groans will garner sympathy and support from others but may

bring no benefits when others are not around. As a result, he may learn to

groan in social settings but not when alone.

Let’s be clear, though, about the

comparison between these stimuli and the stimuli central to classical

conditioning. A CS+ tells the animal about events in the world: “No

matter what you do, the US is coming.” The S+, on the other hand,

tells the animal about the impact of its own behavior: “If you respond now,

you’ll get rewarded.” The CS– indicates that no matter what the

animal does, no US is coming. The S–, in con-trast, tells the animal

something about its behavior—namely, that there’s no point in responding right

now.

Despite these differences,

generalization in instrumental conditioning functions much the way it does in

classical conditioning, and likewise for discrimination. One illustration of

these parallels lies in the generalization gradient. We saw earlier that if an

organism is trained with one CS (perhaps a high tone) but then tested with a

differ-ent one (a low tone), the CR will be diminished. The greater the change

in the CS, the greater the drop in the CR’s strength. The same pattern emerges

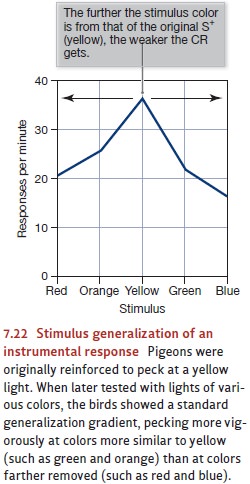

in instrumental condi-tioning. In one experiment, pigeons were trained to peck

at a key illuminated with yellow light. Later, they were tested with lights of

varying wavelengths, and the results showed an orderly generalization gradient

(Figure 7.22). As the test light became less similar to the original S+,

the pigeons were less inclined to peck at it (Guttmann & Kalish, 1956).

The ability to distinguish an S–

from an S+ obviously allows an organism to tune its behavior to its

circumstances. Thus, the dolphins at the aquarium leap out of the water to get

a treat when their feeders are around; they don’t leap up in the presence of

other people. Your pet dog sits and begs when it sees you eating, in hopes that

you’ll share the snack; but the dog doesn’t beg when it sees you drinking. In

these and other cases, behaviors are emitted only when the available stimuli

indicate that the behavior will now be rewarded.

In fact, animals are quite

skilled at making discriminations and can use impressively complex stimuli as a

basis for controlling their behavior. In one study, pigeons were trained to

peck a key whenever a picture of water was in view, but not to peck otherwise.

Some of the water pictures showed

flowing streams; some showed calm lakes. Some pictures showed large bodies of

water photographed from far away; some showed small puddles photographed close

up. Despite these variations, pigeons mastered this discrim-ination task and

were even able to respond appropriately to new pictures that hadn’t been

included in the training trials (Herrnstein, Loveland, & Cable, 1976).

Apparently, pigeons are capable of discriminating relatively abstract

categories—categories not defined in terms of a few simple perceptual features.

Similar procedures have shown that pigeons can discriminate between pictures

showing trees and pictures not showing trees; thus, for example, they’ll learn

to peck in response to a picture of a leaf-covered tree or a tree bare of

leaves, but not to peck in response to a picture of a telephone pole or a

picture of a celery stalk. Likewise, pigeons can learn to peck whenever they’re

shown a picture of a particular human—whether she’s photographed from one angle

and close up or from a very different angle, far away, and wearing different

clothes (Herrnstein, 1979; Lea & Ryan, 1990; for other examples of complex

discriminations, see Cook, K. Cavoto, & B. Cavoto, 1995; Giurfa, Zhang,

Jenett, Menzel, & Srinivasan, 2001; Lazareva, Freiburger, & Wasserman,

2004; D. Premack, 1976, 1978; A. Premack & D. Premack, 1983; Reiss &

Marino, 2001; Wasserman, Hugart, & Kirkpatrick-Steger, 1995; Zentall,

2000).

SHAPING

Once a response has been made,

reinforcement will strengthen it. Once the dolphin has leapt out of the water,

the trainers can reward it, encouraging further leaps. Once the pigeon pecks

the key, food can be delivered, making the next peck more likely. But what

causes the animal to perform the desired response in the first place? What

leads to the first leap or the first peck? This is no problem for many

responses. Dolphins occa-sionally leap with no encouragement from a trainer,

and pecking is something pigeons do all the time. If the trainer is patient,

therefore, an opportunity to reinforce (and thus encourage) these responses

will eventually arrive.

But what about less obvious

responses? For example, rats quite commonly manipu-late objects in their

environment, and so they’re likely to press on a lever if we put one within

reach. But what if we place a lever so high that the rat has to stretch up on its

hind legs to reach it? Now the rat might never press the lever on its own.

Still, it can learn this response if its behavior is suitably shaped. This shaping is accomplished by a little

“coaching,” using the method of successive

approximations.

How could we train a rat to press

the elevated lever? At first, we reinforce the ani-mal merely for walking into

the general area where the lever is located. As soon as the rat is there, we

deliver food. After a few such trials, the rat will have learned to remain in

this vicinity most of the time, so we can now increase our demand. When the rat

is in this neighborhood, sometimes it’s facing one way, sometimes another; but

from this point on, we reinforce the rat only if it’s in the area and facing

the lever. The rat soon masters this response too; now it’s facing in the right

direction most of the time. Again, therefore, we increase our demand: Sometimes

the rat is facing the lever with its nose to the ground; sometimes it’s facing

the lever with its head elevated. We now reinforce the animal only when its

head is elevated—and soon this, too, is a well-established response. We

continue in this way, counting on the fact that at each step, the rat naturally

varies its behavior somewhat, allowing us to reinforce just those variations we

prefer. Thus, we can gradually move toward reinforcing the rat only when it

stretches up to the lever, then when it actually touches the lever, and so on.

Step by step, we guide the rat toward the desired response.

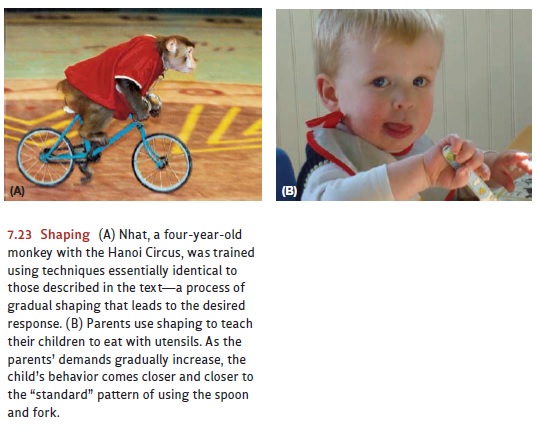

Using this technique, people have

trained animals to perform all kinds of complex behavior; many human behaviors

probably come about in the same way (Figure 7.23). For example, how do parents

in Western countries teach their children to eat with a spoon and fork? At

first, they reward the child (probably with smiles and praise) just for holding

the spoon. This step soon establishes a grasp-the-spoon operant; and, at that

point, the parents can require a bit more. Now they praise the child just when

she touches food with the spoon—and, thanks to this reinforcement, the new

operant is quickly established. If the parents continue in this way, gradually

increasing their expectations, the child will soon be eating in the “proper”

way.

Similar techniques are used in

therapeutic settings to shape the behavior of the hos-pitalized mentally ill.

Initially, the hospitalized patients might be rewarded just for get-ting out of

bed. Once that behavior is established, the requirement is increased so that,

perhaps, the patients have to move around a bit in their room. Then, later, the

patients are rewarded for leaving the room and going to breakfast or getting

their medicine. In this way, the behavior therapist can gradually lead the

patients into a more acceptable level of functioning .

WHAT IS A REINFORCER ?

We’ve now said a great deal about

what reinforcement does; it encourages some responses, discourages others, and

even—through the process of shaping—creates entirely new responses. But what is

it that makes a stimulus serve as a reinforcer?

Some stimuli serve as reinforcers

because of their biological significance. These primary reinforcers include food, water, escape from the scent of a

predator, and so on—all stimuli with obvious importance for survival. Other

reinforcers are social—think of the smiles and praise from parents that we

mentioned in our example of teaching a child to use a spoon and fork.

Other stimuli are initially

neutral in their value but come to act as reinforcers because, in the animal’s

experience, they’ve been repeatedly paired with some other, already established

reinforcer. This kind of stimulus is called a conditioned reinforcer, and it works just like any other

reinforcer. A plausible example is money—a

reward that takes its value from its association with other more basic

reinforcers.

Other reinforcers, however, fall

into none of these categories, so we have to broaden our notion of what a

reinforcer is. Pigeons, for example, will peck in order to gain infor-mation about the availability of

food (e.g., G. Bower, McLean, & Meachem, 1966;Hendry, 1969). Monkeys will

work merely to open a small window through which they can see a moving toy

train (Butler, 1954). Rats will press a lever to gain access to an exer-cise

wheel (D. Premack, 1965; but also Timberlake & Allison, 1974; Timberlake,

1995). And these are just a few examples of reinforcers.

But examples like these make it

difficult to say just what a “reinforcement” is, and in practice the stimuli we

call reinforcements are generally

identified only after the fact. Is a glimpse of a toy train reinforcing? We can

find out only by seeing whether an animal will work to obtain this glimpse.

Remarkably, no other, more informative definition of a reinforcer is available.

BEHAVIORALCONTRASTADINTRINSICMOTIVATION

Once we’ve identified a stimulus

as a reinforcer, what determines how effective the reinforcer will be? We know

that some reinforcers are more powerful than others—and so an animal will

respond more strongly for a large reward than for a small one. However, what

counts as large or small depends on the context. If a rat is used to get-ting

60 food pellets for a response, then 16 pellets will seem measly and the animal

will respond only weakly for this puny reward. But if a rat is used to getting

only 4 pellets for a response, then 16 pellets will seem like a feast and the

rat’s response will be fast and strong (for the classic demonstration of this

point, see Crespi, 1942). Thus, the effectiveness of a reinforcer depends largely

on what other rewards are available (or have recently been available); this

effect is known as behavioral contrast.

Contrast effects are important

for their own sake, but they may also help explain another (somewhat

controversial) group of findings. In one study, for example, nursery-school

children were given an opportunity to draw pictures. The children seemed to

enjoy this activity and produced a steady stream of drawings. The experimenters

then changed the situation: They introduced an additional reward so that the

children now earned an attractive “Good Player” certificate for producing their

pictures. Then, later on, the chil-dren were again given the opportunity to

draw pictures—but this time with no provision for “Good Player” rewards.

Remarkably, these children showed considerably less interest in drawing than

they had at the start and chose instead to spend their time on other

activ-ities (see, for example, Lepper, Greene, & Nisbett, 1973; also Kohn,

1993).

Some theorists say these data

illustrate the power of behavioral contrast. At the start of the study, the

activity of drawing was presumably maintained by certain reinforce-ments in the

situation—perhaps encouragement from the teachers or comments by other

children. Whatever the reinforcements were, they were strong enough to maintain

the behavior; we know this because the children were producing drawings at a

steady pace. Later on, though, an additional reinforcement (the “Good Player”

certifi-cate) was added and then removed. At that point the children were back

to the same rewards they’d been getting at the start, but now these rewards

seemed puny in com-parison to the greater prize they’d been earning during the

time when the “Good Player” award was available. As a consequence, the initial

set of rewards was no longer enough to motivate continued drawing.

Other theorists interpret these

findings differently. In their view, results like this one suggest that there

are actually two different types of reward. One type is merely tacked onto a

behavior and is under the experimenter’s control; it’s the sort of reward

that’s in play when we give a pigeon a bit of food for pecking a key, or hand a

factory worker a paycheck for completing a day’s work. The other type of reward

is intrinsic to the behav-ior and independent of the experimenter’s intentions;

these rewards are in play when someone is engaging in an activity just for the

pleasure of the activity itself.

In addition, these two forms of

reward can interfere with each other. Thus, in the study with the “Good Player”

certificates, the children were initially drawing pictures for an intrinsic

reward. Drawing, in other words, was a form of play engaged in for its own sake. However, once the external

rewards (the certificates) entered the situation, the same activity became a

form of work—something you do for a

payoff. And once the

activity was redefined in this

way, then the absence of a payoff meant there was no longer any point in

drawing.

Debate continues about which of

these interpretations is preferable—the one based on behavioral contrast or the

one based on intrinsic motivation. (It also seems plausi-ble that both interpretations may capture aspects

of what’s going on here.) Clearly, there’s more to be learned about

reinforcement and the nature of motivation. (For further exploration, see

Bowles, 2008; Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999a, 1999b; Eisenberger, Pierce,

& Cameron, 1999; Henderlong & Lepper, 2002.)

SCHEDULES OF REIN FOR CEMENT

Let’s now return to the issue of

how extrinsic reinforcements work, since—by any-one’s account—these

reinforcements play a huge role in governing human (and other species’)

behavior. We do, after all, work for money, buy lottery tickets in hopes of

winning, and act in a way that we believe will bring us praise. But notice that

in all of these examples, the reinforcement comes only occasionally: We aren’t

paid after every task we do at work; we almost never win the lottery; and we

don’t always get the praise we seek. Yet we show a surprising resistance t0

extinction of those behaviors. About some things, we have learned that if you

don’t succeed, it pays to try again— an important strategy for achieving much

of what we earn in life.

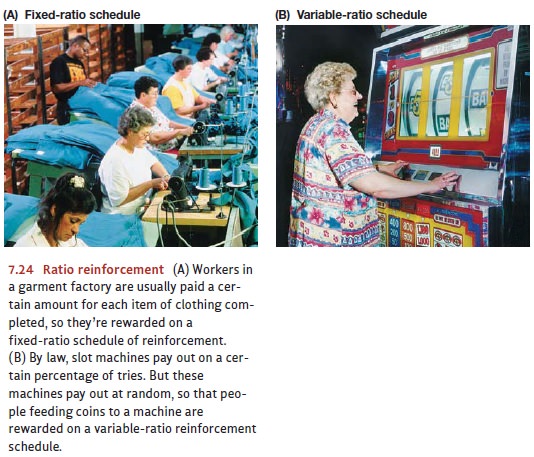

This pattern, in which we’re

reinforced for only some of our behaviors, is known as partial reinforcement. In the laboratory, partial reinforcement can

be provided according to different schedules

of reinforcement—rules about how often and under what conditions a response

will be reinforced. Some behaviors are reinforced via a ratio schedule, in which you’re rewarded for producing a certain

number of responses (Figure 7.24). The ratio can be “fixed” or “variable.” In a

“fixed-ratio 2” (FR 2) schedule, for example, two responses are required for

each reinforcement; for an “FR 5” schedule, five responses are required. In a

variable-ratio schedule, the number of responses required changes from trial to

trial. Thus, in a “VR 10” sched-ule, 10 responses are required on average to get a reward—so it might

be that the first 5 responses are enough to earn one reward, but 15 more are

needed to earn the next.

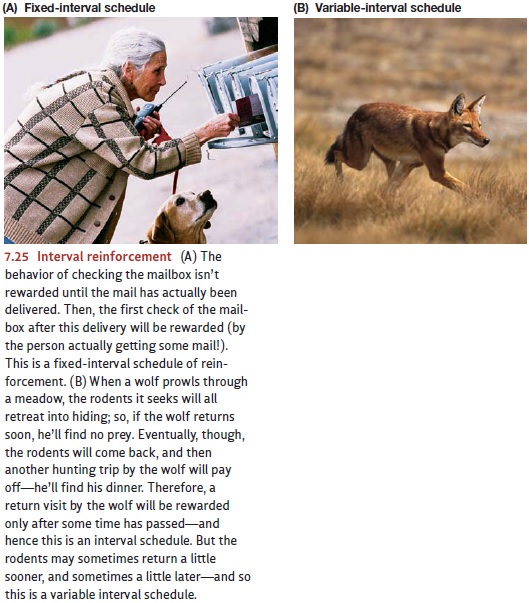

Other behaviors are reinforced on

an interval schedule, in which

you’re rewarded for producing a response after a certain amount of time has

passed (Figure 7.25). Thus, on an “FI 3-minute” schedule, responses made during

the 3-minute interval aren’t rein-forced; but the first response after the 3

minutes have passed will earn a reward. Interval schedules can also be

variable: For a “VI 8-minute” schedule, reinforcement is available on average

after 8 minutes; but the exact interval required varies from trial to trial.

Related Topics