Chapter: Psychology: Learning

Classical Conditioning: Extinction

EXTINCTION

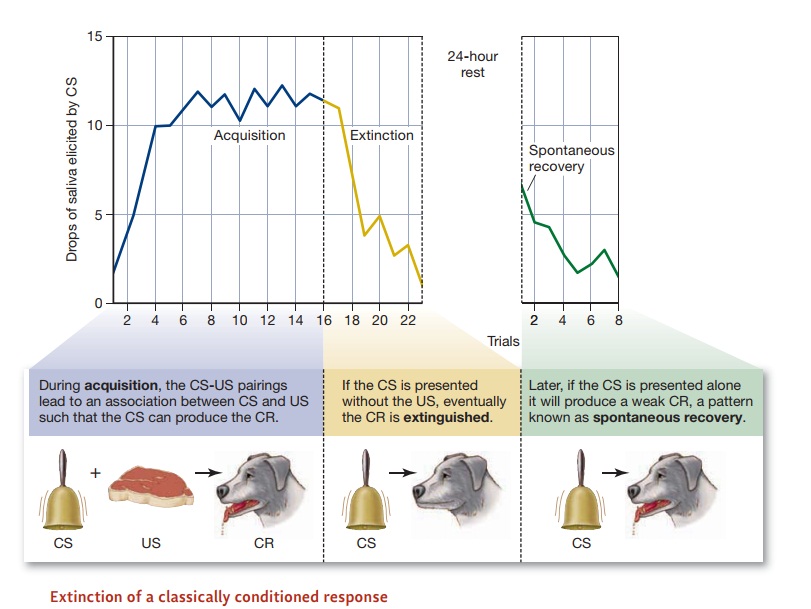

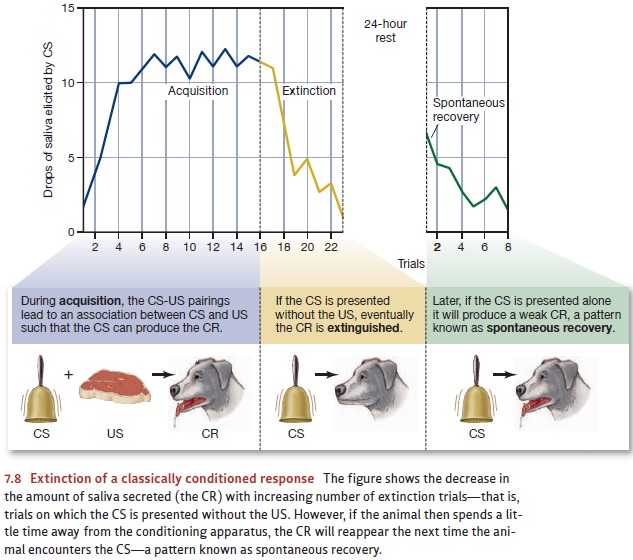

Classical conditioning can have

considerable adaptive value. Imagine a mouse that has several times seen the

cat resting on a kitchen chair. It would serve the mouse well to learn about

this asso-ciation between the cat and a particular location; that way, the

mouse will likely feel afraid whenever it nears the kitchen. This fear, in

turn, will probably lead the mouse to avoid that room—a habit that could save

the mouse’s life!

At the same time, it would be

unfortunate for the mouse if this association, once established, could never be

undone. The cat might lose interest in that resting place or leave the

household altogether. Either way, it would be useful for the mouse to lose its

fearful response to the kitchen so it can return there to forage for food.

All is well for this mouse,

though, because the effects of classical conditioning can be undone through a

sequence of events similar to those that established the conditioning in the

first place. Pavlov demonstrated that the CR will gradually disappear if the CS

is pre-sented several times by itself—that is, without the US. For example,

repeated pairings of light plus a blast of cold air will create a condi-tioned

response, so that the animal will shiver (the CR) whenever the light (the CS)

is presented. But if the light is then presented sev-eral times on its own, the

shivering response will be extinguished.Extinction is the undoing of a

previously learned response so that the response is no longer produced (Figure

7.8).

Let’s be clear, though, that

extinction is not just the result of an animal forgetting what it learned

earlier. Of course, animals (including humans) do eventually forget things they

once learned, but that is not what’s going on in extinction. This point is

evident, for exam-ple, in the speed of extinction. As Figure 7.8 shows, a

response can be extinguished in just a half-dozen trials over a period of only

a few minutes. In contrast, forgetting is far slower: To demonstrate this, we

can condition an animal, then leave it alone for several weeks, and then test

it by presenting the CS. In this cicumstance, we have arranged for no

extinction trials, but we have provided an opportunity for forgetting. The

result of this procedure is clear: Even after a substantial delay, the animal

is likely to exhibit a full-blown conditioned response (B. Schwartz, Wasserman,

& Robbins, 2005). It seems, then, that classically con-ditioned responses

are forgotten only very slowly.

The difference between extinction and forgetting is also clear in another procedure. First we condition an animal by repeated pairings of CS and US; then we extinguish the learning by presenting the CS on its own. In a third step, we recondition the same animal—by presenting some more learning trials, just like those in the first step of the procedure. What happens? The reconditioning usually takes much less time than the initial conditioning did. The speed of relearning, in other words, is faster than the orig-inal rate of learning. Apparently, then, extinction doesn’t “erase” the original learning and return the animal to its original naive state. Instead, the animal still has some memory of the learning, and this gives it a head start in the reconditioning trials.

We can draw similar conclusions

about extinction from the phenomenon of spontaneous

recovery. This phenomenon is observed in animals that have beenthrough an

extinction procedure and then left alone for a rest interval. After this rest

period, the CS is again presented, and now the CS often elicits the CR—even

though the CR was fully extinguished earlier (see Figure 7.8).

According to one view of this

effect, the extinction trials lead the animal to recognize that a once

informative stimulus is no longer informative. The bell initially signaled that

food would be coming soon; but now, the animal learns, the bell signals

nothing. However, the animal still remembers that the bell was once

informative; so when a new experimental session begins, the animal checks to

see whether the bell will again be informative in this new setting. Thus, the

animal resumes responding to the bell, pro-ducing the result we call

spontaneous recovery (Robbins, 1990).

Like all aspects of conditioning,

spontaneous recovery can easily be observed out-side of the laboratory and in

humans. For example, various anxiety disorders are often treated via exposure therapy—a process modeled after

the extinction procedure. In this process, the person is repeatedly exposed to

the specific stimulus or the particular situ-ation that has, for that person,

been a source of anxiety—heights, say, or enclosed spaces, or the sight of a

snake. During these exposures, the person is kept safe and comfortable—and so

there’s no fearful US associated with the CS. As we’d expect, this sequence of

events leads to extinction of the CR (the feelings of anxiety)—and with each

exposure, the person feels less and less anxious.

When exposure therapy ends, however,

people often relapse and again become anxious when exposed to the phobic

stimulus. This relapse is not a sign that the therapy has failed. It’s simply

an example of spontaneous recovery of a CR—a sign that more treatment is needed

to eliminate the anxiety.

Related Topics