Chapter: Psychology: Learning

Classical Conditioning: Contingency

CONTINGENCY

TheCS’s role as a signal also has

a crucial implication for what produces

classical conditioning—that is, what the relationship between the CS and the US

must be for learning to occur. To understand the issue, consider a dog in a

conditioning experi-ment. Several times, it has heard a metronome and, a moment

later, received some food powder. But many other stimuli were also present. At

the same time it heard the metronome, the dog heard some doors slamming and

some voices in the background. It saw the laboratory walls and the light

fixtures hanging from the ceiling. At that moment, it could also feel various

bodily sensations. What, therefore, should the dog learn? If it relies on mere

contiguity, it will learn to associate the food powder with all of these

stimuli—metronomes, light fixtures, and everything else on the scene—since they

were all present when the US was introduced.

Notice, though, that many of

these stimuli—even if contiguous with the US—give no information about the US.

The light fixtures, for example, were on the scene just before the food powder

arrived; but they were also on the scene during the many min-utes when no food

was on its way. So the sight of the light fixtures can’t signal that food is

coming soon, because the presence of the light fixtures has just as often

conveyed the opposite message. Likewise for most of the sounds in the laboratory;

they were present just before the food arrived, but they were also present

during minutes without food. Therefore, none of these stimuli will help the

animal predict when food is coming and when it’s not.

To predict the US’s arrival, the

dog needs some event that reliably occurs when food is about to appear and

doesn’t occur otherwise. And, of course, the metronome beat in our example is

the only stimulus that satisfies this requirement, since it never beats in the

intervals between trials when food is not presented. Therefore, if the animal

hears the metronome, it’s a safe bet that food is on its way. If the animal

cares about signal-ing, it should learn about the metronome and not about these

other stimuli, even though they were all contiguous with the target event.

Are animals sensitive to these

patterns? Said differently, what is it that leads to clas-sical conditioning?

Is it contiguity—the fact that the CS

and US arrive close to each other in time? Or is it contingency—the fact that the CS provides information about the

US’s arrival? It turns out that contingency is the key, and in fact a CR is

acquired only when the CS is informative about things to come.

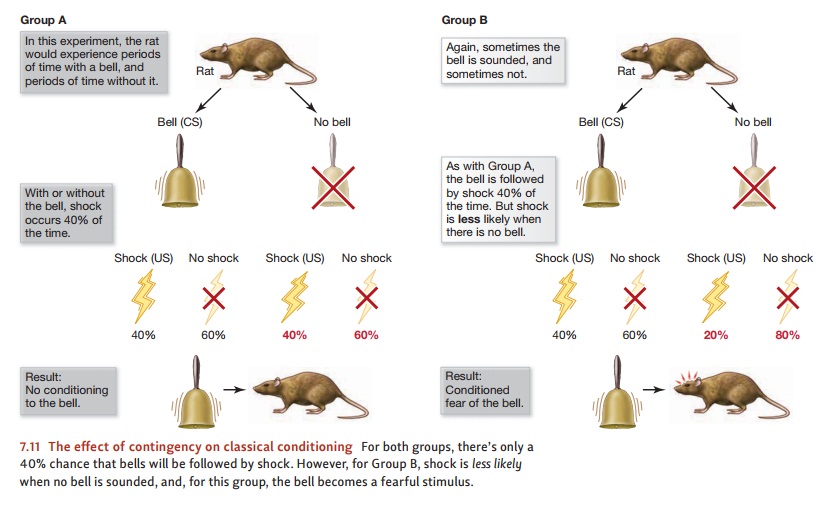

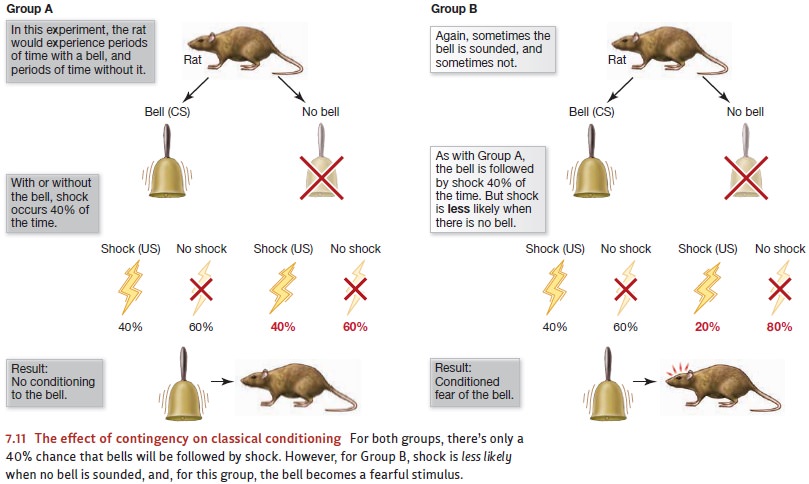

In one experiment, rats were

exposed to various combinations of a bell (CS) and a shock (US) (Figure 7.11).

The bell was never a perfect predictor of the shock, but it did signal that

shock was likely to arrive soon. Specifically, presentation of the bell

signaled a 40% chance that a shock was about to arrive.

For some of the rats in this

experiment (Group A in the figure), shocks also arrived 40% of the time without

any warning. For these rats, therefore, the bell pro-vided no information. The

likelihood of a shock following the bell was exactly the same as the likelihood

of shock in general. And in fact this situation led to no condi-tioning;

instead, the rats simply learned to ignore the tone.

For another group of rats (Group

B in the figure), the bell still signaled a 40% chance of shock, and shocks

still arrived occasionally without warning. For these ani-mals, though, the

likelihood of a shock was only 20% when there was no bell. So in this setting,

the bell was an imperfect predictor but it did provide some information,

because shock was more likely after the bell than otherwise. And, in this

situation, the rats did develop a conditioned response—they became fearful

whenever the bell was sounded.

Let’s be clear that in this

experiment, the two groups of rats experienced the same number of bell-shock

pairings, and so the degree of contiguity between bell and shock was the same

for both groups. What differed between the groups, though, was whether the bell

was informative or not—and it’s this information value, not the contiguity,

that matters for conditioning. Notice also that the bell was never a perfect

predictor of shock: Bells were not

followed by shock 60% of the time. Even so, conditioning was observed;

apparently, an imperfect predictor is better than no predictor at all

(Rescorla, 1967, 1988; Figure 7.12).

Related Topics