Chapter: Psychology: Learning

Classical Conditioning: Generalization

GENERALIZATION

In Pavlov’s early experiments,

animals were trained with a particular CS—the sound of a bell or metronome, for

example—and then later tested with that same stimulus. But Pavlov understood

that life outside the lab is more complicated. The master’s voice may always

signal food, but his tone of voice varies from one occasion to the next. The

sight of an apple tree may well signal the availability of fruit, but apple

trees differ in size and shape. Because of these variations, animals must be

able to respond to stimuli that aren’t identical to the original CS; otherwise,

the animals may obtain no benefit from their earlier learning.

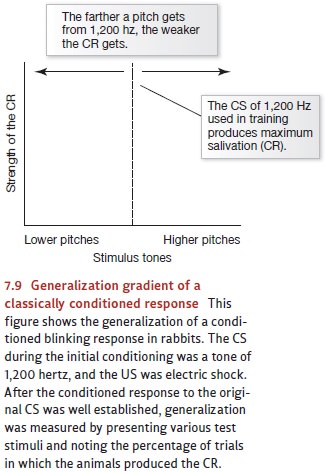

It’s not surprising, therefore,

that animals show a pattern called stimulusgeneralization—that

is, they respond to a range of stimuli, provided that these stimuliare similar

enough to the original CS. Here’s an example: A dog might be conditioned to

respond to a tone of a particular pitch. When tested later on, that dog will

respond most strongly if the test tone is that same pitch. But the dog will

also respond, although a bit less strongly, to a tone a few notes higher. The

dog will also respond to an even higher tone, but the response will be weaker

still. In general, the greater the difference between the new stimulus and the

original CS, the weaker the CR will be. Figure 7.9 illustrates this pattern,

called a generalization gradient. The

peak of the gradient (the strongest response) is typically found when the test

stimulus is identical to the conditioned stimulus used in training. As the

stimuli become less like the original CS, the response gets weaker and weaker

(so the curve gets lower and lower).

Related Topics