Chapter: Biochemistry: Viruses, Cancer, and Immunology

The Immune System: Distinguishing Self from Nonself

Distinguishing Self from Nonself

With all the power the immune system has to attack foreign invaders, it must also do so with discretion, because we have our own cells that display proteins and other macromolecules on their surfaces. How the immune system knows not to attack these cells is a complicated and fascinating topic. When the body makes a mistake and attacks one of its own cells, the result is an autoimmune disease, examples of which are rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and some forms of diabetes.

T cells and B cells have a wide variety of receptors on their

surfaces. The affinities for a given antigen vary greatly. Below a certain

threshold, an encoun-ter between a lymphocyte receptor and an antigen is not

sufficient to trigger that cell to become active and begin to multiply. These

same cells also have stages of development. They mature in the bone marrow or

the thymus and go through an early stage in which receptors first begin to

appear on their surfaces.

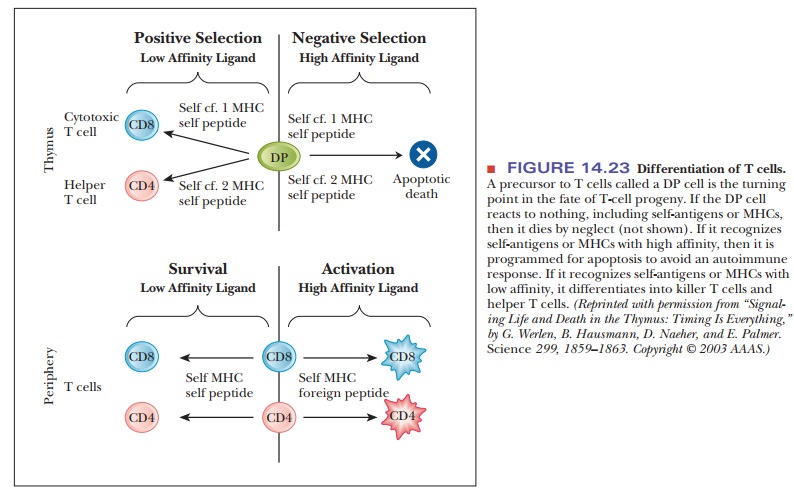

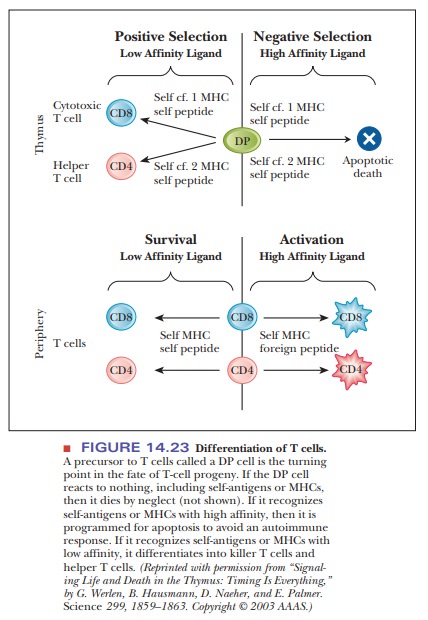

In the case of T cells, a precursor form called a DP cell has both the CD4 and the CD8

protein. This cell is the turning point for the fate of its progeny. If the

receptors of the DP cell do not recognize anything, including self-antigens or

self-MHC proteins, then it dies by neglect. If the receptors recognize

self-antigens or MHC but with low affinity, then the cell undergoes positive

selection and dif-ferentiates into a killer T cell or a helper T cell, as shown

in Figure 14.23. On the other hand, if the cell’s receptors encounter

self-antigens that are recognized with high affinity, it undergoes a process

called negative selection and is

pro-grammed for apoptosis, or cell death.

By the time the lymphocytes leave their tissue of origin, they have

therefore already been stripped of the most dangerous individual cells that

would tend to react to self-antigens. Some individual cells will still have a

receptor with very low affinity for a self-antigen. If these slip out of the

bone marrow or thymus, they do not initiate an immune response because their

affinity is below the minimum threshold, and there is always the requirement

for a secondary sig-nal. They would need to have another cell, such as a

macrophage, also present them with an antigen. In the case of B cells, besides

binding an antigen to its receptor, it would need to receive an interleukin 2

from a helper T cell that had also been stimulated by the same antigen.

All of these safeguards lead to the delicate balance that must be

maintained by the immune system, a system that simultaneously has the diversity

to bind to almost any molecule in the Universe but does not react to the myriad

proteins that are recognized as self.

Related Topics