Chapter: Biology of Disease: Disorders of the Blood

Thalassemias - Hemoglobinopathies

THE THALASSEMIAS

Thalassemia, from ‘thalassa’,

which is Greekof

hemoglobinopathies

originally discoveredfor ‘the

sea’, are a

group in people living

near theMediterranean sea.

However, the thalassemias are also relatively common in southeastern Asia, the

Philippines, China and worldwide and is perhaps the most common group of

hereditary diseases. Cooley first accurately described them clinically in 1925

and the disease used to be called Cooley’s anemia, a term now reserved for β-thalassemia.

In the late 1930s, thalassemia was shown to be an inherited

disorder. However, it was not until protein analytical techniques improved in

the 1960s that the disease was shown to be the result of an imbalance in the

amounts of α - and β-globins synthesized. The severe anemias associated

with some thalassemias stimulate the production of erythrocyte precursors. As a

result, bone marrow is able to expand to all areas of the skeleton leading to

skeletal deformities. If this occurs within the spine and compresses the spinal

cord it can cause intense pain. Some forms of the disease are fatal causing

death in utero, while others require

copious blood transfusions for the anemia. α -Thalassemia, for example, is caused by a complete or partial

failure to produce α -globin. It is fatal in its

severe form when α -chains are not produced. In β -thalassemia, a partial or complete failure to

produce β -globin means that patients require lifelong blood

transfusions.

There are a number of forms of the disease because there is more

than one gene for the globin polypeptides and a mutation may not affect all of

them. Consequently there may not be complete absence of a given globin chain

and the disease will be less severe. Thalassemias are classified according to

which globin chains are reduced in amount, are mutated or are absent. The more

copies of the gene are missing or inactive, the greater the severity of the

disease. The anemia is caused by an ineffective erythropoiesis and from

precipitation of excess free globin within the erythrocytes. The cells have a

shortened life span and the spleen removes the abnormal erythrocytes leading to

splenomegaly.

α-Thalassemias can vary from a

condition in which only one α -globin chain is missing, producing a ‘silent’ mutation that is

practically a symptom-free, carrier state, to other forms where two, three or

all four genes are absent or inactive (Table

13.6). The presence of a single functional α -globin gene is usually sufficient to preclude serious

morbidity. A decreased synthesis of α-globin leads to the formation of two abnormal Hb tetramers.

Hemoglobin Barts is found in umbilical cord blood and arises because of a lack

of α -chains but normal production of the fetal γ -chains; thus Hb Barts is γ 4. If the infant survives, β-chain synthesis begins and β 4 (HbH) tetramers form. Unfortunately, neither γ 4 nor β 4 can take up cooperatively O2

but bind it so tightly it cannot be delivered to the tissues. Hemoglobin H

precipitates in older erythrocytes

and under oxidant stress, such as when the patient is treated

for malaria with primaquine. A total absence of a α-globin gene results in the lethal in utero condition, hydrops fetalis.

Some mutations that produce thalassemia are referred to as

nondeletion mutations. The mutation occurs in the STOP codon for the α -chain, consequently translation continues beyond

the normal end point to the next STOP codon, extending the polypeptide by 31

residues. An example of this produces Hb Constant Spring, the incidence of

which is fairly common in southeastern Asian populations where the usual STOP

codon UAA is mutated to CAA. It appears that the extended mRNA for the α -chain is unstable and leads to a reduced rate of Hb

synthesis. If this mutation is present together with a lack of one of the α-globin genes, then HbH disease results. However, in

heterozygotes only about 1% of the α -globin produced is the Constant Spring mutant type.

β-Thalassemias result from mutations in the β-globin genes. In some ways, it would be more appropriate to call

them ‘thalassemias of the β -globin gene family’ because the genes for D-, and γ-globins and the single β -globin are all grouped together on chromosome 11. In β -thalassemia there is reduced synthesis of β-globin with or without a reduced synthesis of D- or γ -globins. β -Thalassemia is not a single disease. The molecular defects in this

and related disorders are highly heterogeneous, with about 200 mutations having

been identified to date. These include many single nucleotide substitutions

that affect the expression of β-globin genes. Examples include nonsense and frameshift mutations

in the exons, point mutations in the intron–exon splice junctions and mutations

in the 5’ region and the 3’-polyadenylation sites. The latter are extended sequences of

adenine nucleotides at the 3’ end of mRNA molecules that

stabilize the mRNA molecules and help in their transport from the nucleus to

the cytoplasm. A number of heterozygous states are also known but these usually

only give rise to mild clinical symptoms. In some forms of β -thalassemia, abnormal D- β fusion polypeptides may be formed. For example, in Hb Lepore

there is a fusion gene caused by nonhomologous crossing over between the D-gene on one chromosome and the β -gene on the other. Thus normal β - and D-genes are absent.

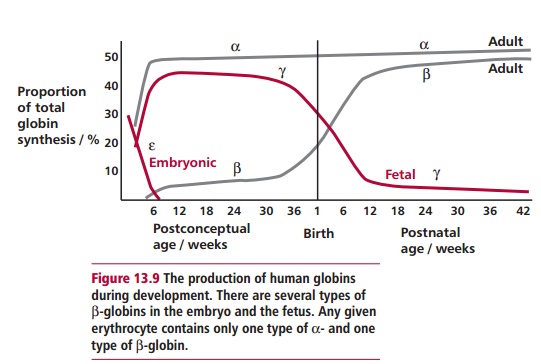

β-Globin chains are not required until after birth (Figure 13.9) and β -thalassemia infants are usually born normally at

term. Clinical problems begin two to six months later, when γ-globin synthesis, and therefore the amount of HbF,

has declined. Consequently β -thalassemia is a crippling disease of childhood, characterized

by the precipitation of excess α -globin chains, destruction of erythrocytes in the bone marrow

and circulation, and deficiency of functional Hb tetramers. In β -thalassemia major, formerly Cooley’s anemia, β -globin synthesis is strongly depressed or absent

causing massive erythroid proliferation and skeletal deformities.

Thalassemias can be diagnosed from their general clinical

symptoms and the anemia, including the precipitation of excess free globin

chains. Hypochromic erythrocytes with a clear center and a darker rim

containing the Hb are visible in blood smears as are poikilocytes, which are

abnormally shaped cells produced by the spleen when it removes target cells.

There is also splenomegaly. Electrophoresis of hemolyzed erythrocytes will

provide information about the relative proportions of A, A2 and F

globins. In HbH disease, the Hb (tetramer of β -globin) is detected as a rapidly moving band at pH 8.4.

The treatment for thalassemias, as with sickle cell disease, is

to give repeated blood transfusions combined with chelation therapy to remove

the iron with, for example, desferrioxamine. The latter is necessary because

the body has no real excretion route for iron, and an iron overload may be

fatal due to deposition cardiomyopathy by the second decade of life.

Transfusions may also put the patient at risk from hepatitis and AIDS,

especially in developing countries. Other treatments, such as giving

hydroxyurea to augment HbF synthesis, are also used (see above) and local irradiation may bring immediate relief when

expansion of bone marrow has happened.

In general, β -thalassemias are more severe, cause more patient suffering and

are more expensive to treat because more medical intervention is required, than

is the case with α-thalassemias.

Related Topics