Chapter: Basic Radiology : Radiology of the Chest

Radiology of the Chest: Technique Selection

TECHNIQUE

SELECTION

The number of diseases and

clinical situations for which a chest radiograph may be indicated is so large

that an ex-haustive listing of individual indications is prohibitive. As a

general rule, however, conventional radiographs should be obtained for any

patient with symptoms suggesting dis-ease of the heart, lungs, mediastinum, or

chest wall. In ad-dition, a chest radiograph is indicated for patients with

systemic diseases that have a high likelihood of secondary involvement of those

structures. Examples of the former are pneumonia and congestive heart failure

and of the lat-ter are a primary extrathoracic neoplasm and connective tissue

disease.

In an acutely ill patient, the

portable chest radiograph is an invaluable tool for monitoring the patient’s

car-diopulmonary status. These radiographs are also used for monitoring of

life-support hardware, such as central venous access catheters, nasogastric tubes,

and endotra-cheal tubes.

Fluoroscopy provides real-time

imaging of the chest. Flu-oroscopy may be used to evaluate the motion of the

di-aphragm in a patient with suspected diaphragmatic paralysis. A paralyzed

hemidiaphragm has sluggish motion as the pa-tient breathes, and as the patient

takes in a quick breath of air, it moves paradoxically upward as the normal

hemidi-aphragm moves downward (“sniff test”). Fluoroscopy and fluoroscopically

positioned spot images are also useful for identification of calcification

within a pulmonary nodule, within coronary arteries, or within cardiac valves.

Fluoro-scopic guidance can also be used for percutaneous transtho-racic needle

biopsy of lung masses.

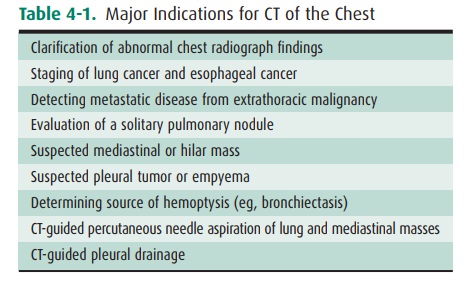

Because the three dimensions of

the thorax are captured on a single two-dimensional chest radiograph,

superimposi-tion of structures within the thorax may result in confusing

shadows. Because CT provides images without this overlap, it is frequently used

to clarify confusing shadows identified on conventional radiographs (Table

4-1). These examina-tions are also used to detect disease that is occult

because of small size or a hidden position. Because of its wider range of

density discrimination, CT can demonstrate mediastinal and chest wall

abnormalities earlier than is possible with conventional chest radiography.

Abnormalities of hilar structures can be identified on CT scans because of the

de-creased overlap of the complex structures of the hilum. CT scans of the

chest are routinely ordered for oncology pa tients, both for evaluation of the

extent of disease at presen-tation and for monitoring response to therapy or

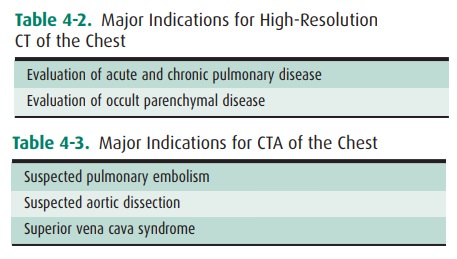

progres-sion of disease. CT is useful for evaluation of the lungparenchyma, as

thin sections (1 to 2 mm thick) reveal great anatomic detail. Thin-section CT

(or high-resolution CT [HRCT]) may enable detection of occult pulmonary

parenchymal disease and may be used for following the course of known pulmonary

disease (Table 4-2). HRCT is especially useful in the diagnosis of interstitial

lung diseases. Additionally, CT angiography (CTA) of the chest is particu-larly

useful for the evaluation of vascular pathology as well as pulmonary embolus

(Table 4-3). Because intravenous contrast material can be administered,

vascular structures may be evaluated and the technique may be useful in

pa-tients with aortic dissection, aortic aneurysm, and superior vena caval

obstruction. Because the cost of CT is approxi-mately 10 to 20 times that of a PA

and lateral chest radi-ograph, CT is not practical for monitoring the course of

diseases on a daily basis.

The diseases and situations for

which nuclear medicine techniques are helpful are determined for the most part

by the radioactive tracer, and these have been outlined in the technique

section (Table 4-4).

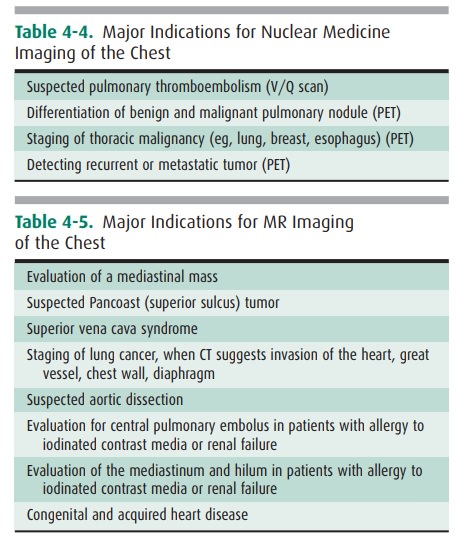

MR imaging of the thorax is most

commonly used for car-diovascular imaging, but there are indications for MR

imag-ing in mediastinal and pulmonary parenchymal imaging as well (Table 4-5).

MR is helpful when bronchogenic carcinoma is suspected of invading vascular

structures, including the cardiac chambers, pulmonary arteries and veins, and

the superior vena cava. In a patient with suspected Pancoast’s (superior

sulcus) tumor (Figure 4-9), MR imaging is pre-ferred to CT because of the

ability to obtain images in coronal and sagittal planes. The apex of the lung

can be difficult to evaluate on axial images alone because of partial-volume

effects.

Ultrasonography is useful for

imaging the soft tissues of the chest wall, heart, and pericardium, as well as

fluid collec-tions within the pleural space. Large, mobile pleural effusions

are usually aspirated without sonographic guidance, because these collect

predictably within dependent areas of the tho-rax. On the other hand, loculated

pleural fluid collections may be difficult to aspirate without guidance, and

the most appropriate entrance site may be marked with sonography for easier

access. Ultrasonography has been used for guidance for biopsy of peripheral

lung lesions as well.

Related Topics