Chapter: Psychology: Treatment of Mental Disorders

Psychological Treatments: Humanistic Approaches

Humanistic Approaches

We

have seen that Freud played a pivotal role in launching the treatment that we

now call psychotherapy; indeed, the idea of a “talking cure” that could help

someone deal with mental distress through conversation or instruction was

essentially unknown before Freud. Nonetheless, most modern psychotherapists

employ methods very different from Freud’s and base their therapies on

conceptions that explicitly reject many of Freud’s ideas.

As we discussed, psychologists who take a humanistic approach have regarded psychoanalysis as being too concerned with basic urges (like sex and aggres-sion) and not concerned enough with the search for meaning. This orientation led them to propose several different types of therapy, which have in common the idea that people must take responsibility for their lives and their actions and live fully in the present.

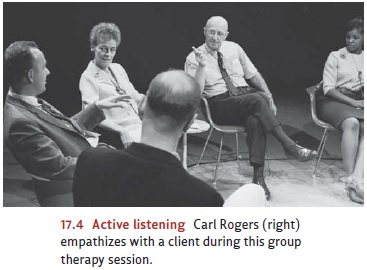

Carl

Rogers’s client-centered therapy

seeks to help a person accept himself as he is and to be himself with no

pretense or self-imposed limits. In this therapy, the ther-apist listens

attentively and acceptingly to the patient (Figure 17.4). The therapist is not

there to question or to direct, but to create an atmosphere in which the

patient feels valued and understood (Rogers, 1951, 1959). Based on his analysis

of his own and others’ therapeutic attempts, Rogers concluded that three factors

were crucial to a therapist’s success: genuineness,

or sharing authentic reactions with the patient; unconditional positive regard, which refers to a nonjudgmental and

accepting stance; and empathic

understanding, which refers to sensing what it must be like to be in the

patient’s shoes (Rogers, 1980).

Rogers’s

therapeutic stance is evident in the following interaction with a patient:

PATIENT:

I cannot be the

kind of person I want to be. I guess maybe I haven’t the guts or the strength

to kill myself, and if someone else would relieve me of the responsi-bility or

I would be in an accident, I—just don’t want to live.

ROGERS:

At the present

time things look so black that you can’t see much point in living.

PATIENT:

Yes, I wish I’d

never started this therapy. I was happy when I was living in my dream world.

There I could be the kind of person I wanted to be. But now there is such a

wide, wide gap between my idea and what I am . . .

ROGERS:

It’s really tough

digging into this like you are, and at times the shelter of your dream world

looks more attractive and comfortable.

PATIENT:

My dream world or

suicide . . . So I don’t see why I should waste your time coming in twice a

week—I’m not worth it—what do you think?

ROGERS:

It’s up to you. .

. . It isn’t wasting my time. I’d be glad to see you whenever you come, but

it’s how you feel about it.

PATIENT:

You’re not going

to suggest that I come in oftener? You’re not alarmed and think I ought to come

in every day until I get out of this?

ROGERS:

I believe you’re

able to make your own decision. I’ll see you whenever you want to come.

PATIENT:

I don’t believe

you are alarmed about—I see—I may be afraid of myself but you aren’t afraid for

me.

ROGERS:

You say you may be

afraid of yourself and are wondering why I don’t seem to be afraid for you.

PATIENT:

You have more

confidence in me than I have. I’ll see you next week, maybe.

[The

patient did not attempt suicide.]

Rogers’s

client-centered therapy has, in turn, inspired a number of other forms of

intervention, one of which is motivational-enhancement

therapy (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). This is a brief, nonconfrontational,

client-centered intervention designed to change problematic behavior (such as

alcohol and other drug use) by reducing ambiva-lence and clarifying discrepancies

between how individuals are actually living and how they say they would like to

live (Ball et al., 2007).

A

second humanistic therapy is Fritz Perls’s Gestalt

therapy. Perls was a highly charismatic and original clinician who was

trained psychodynamically but drew inspi-ration from the gestalt theory of

perception. Perls believed that psycho-logical difficulties stemmed from a

failure to integrate mutually inconsistent aspects of self into an integrated

whole or gestalt. His techniques were aimed at helpingpatients become aware of

and then integrate disparate aspects of self by increasing self-awareness and

self-acceptance (Perls, 1967, 1969).

For

example, Perls was famous for asking his patients about what they were feeling

in the moment, and for pointing out apparent discrepancies between what they

said they felt and how they appeared to be feeling. Perls also used the empty chair technique, in which a

patient imagines that he is seated across from another person, such as his

parent or his partner, and tells him honestly what he feels. Using such

strategies, Perls helped his patients acknowledge and confront their feelings.

In

more modern versions of humanistic therapies—collectively referred to as the experiential therapies—these approaches

are integrated, seeking to create a genuinelyempathic and accepting atmosphere

but also to challenge the patient in a more active fashion with the aim of

deepening his experience (Elliott, Greenberg, & Lietaer, 2004; Follette

& Greenberg, 2005). This approach views the patient and, indeed, all humans

as oriented toward growth and full development of their potential, and the

therapist uses a number of techniques to encourage these tendencies.

Although

these challenges to live more actively and deeply can be disconcerting,

experiential therapies involve genuine concern and respect for the person, with

an emphasis on all her qualities, and not just those symptoms that led to a

particular diagnosis. The person’s subjective experience is also a primary

focus, and the thera-pist tries to be as empathic as possible, in order to

understand that experience. Moreover, experiential therapists reject Freud’s

notion of transference; in their view, the relationship between patient and

therapist is a genuine connection between two people, one that provides the

patient with an opportunity for a new, emotionally validating experience.

Related Topics