Chapter: Psychology: Treatment of Mental Disorders

Early Treatments for Mental Disorders

Early Treatments for Mental Disorders

The

early idea that mental disorders were caused by evil spirits suggested a number

of strategies for treatment. In some cases, large holes were cut in a person’s

skull, so that the demons could be driven out through this “exit.” Other

treatments sought to calm the demons with music, to chase them away with prayers,

or to purge them with potions that induced vomiting. Another approach was to

make the evil spirits so uncomfortable in the patient’s body that they would be

induced to flee. Accordingly, patients were starved, flogged, or immersed in

boiling water. Not surprisingly, these treatments did not work and often made

patients worse.

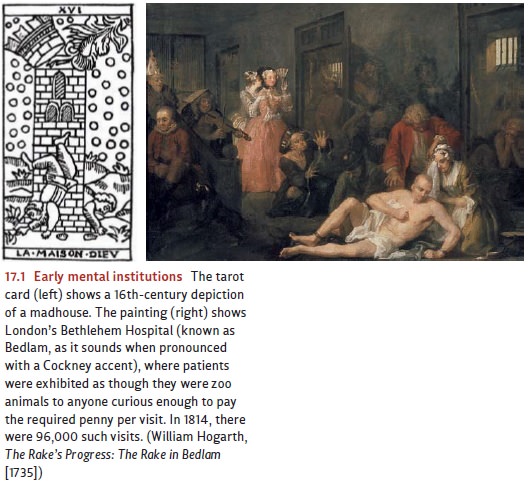

As

we saw, recent centuries have seen the rise of a very different con-ception of

mental illness, one that treats mental disorders as physical diseases like any

other. Unfortunately, this conception has not always lead to more humane

treatment of the afflicted. In the Middle Ages, diseased “madmen” were given

little sympathy, and the interests of society were deemed best served by

“putting them away.” Beginning in the 16th century, a number of special

hospitals for the insane were estab-lished throughout Europe (Figure 17.1). But

most of these institutions were hospitals in name only. Their real function was

to confine all kinds of social “undesirables” and isolate them from the rest of

humanity. Criminals, beggars, epileptics, and “incurables” of all sorts were

institutionalized and treated along with the mentally disturbed. And the

treatments were barbaric. One author described conditions in the major mental

hospital for Parisian women at the end of the 1700s: “Madwomen seized by fits

of violence are chained like dogs at their cell doors, and separated from

keepers and visitors alike by a long corridor protected by an iron grille;

through this grille is passed their food and the straw on which they sleep; by

means of rakes, part of the filth that surrounds them is cleaned out”.

Gradually, reformers succeeded in eliminating the worst of these practices. The French physician Philippe Pinel (1745–1826), for example, was put in charge of the Parisian hospital system in 1793, at the height of the French Revolution. Pinel wanted to remove the inmates’ shackles and chains and give them exercise and fresh air; the government permitted these changes—although only grudgingly. A half century later, in the United States, a retired schoolteacher named Dorothea Dix became a passionate advocate for appropriate treatment for the mentally ill. In her report to the Massachusetts legislature in 1843, Dix said: “I come as the advocate of helpless, forgot-ten, insane, and idiotic men and women; of beings, sunk to a condition from which the most unconcerned would start with a real horror. . . . I proceed, Gentlemen, briefly to call your attention to the present state of Insane Persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, closets, cellars, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience”. Dix’s report is, of course, apowerful indictment of the treatment of the mentally ill in 19th-century America, and fortunately the indictment had an effect. Dix’s tireless work on behalf of the mentally ill was an important impetus to the dramatic growth of state-supported institutions for mental care during the latter part of the 19th century.

Amid

calls for reform, other developments in the 19th century profoundly shaped how

people thought about, and tried to treat, mental illness. One triumph was the

treatment of paresis . This was important for its own sake, but it can also be

under-stood as the leading edge of a much larger trend, and, across the next

decades, it became more and more common to take a medical perspective on mental

illness—in many cases, this meant treatment via medications of one sort or

another. Another major develop-ment, also at the end of the 19th century, was

the advent of Freud’s “talking cure.” This treatment proved to be the first in

a long line of psychological therapies, which collectively drew attention to

the environmental and social dimensions of mental illness and provided many

powerful tools for treating mental disorders.

Related Topics