Chapter: Psychology: Treatment of Mental Disorders

Meta-Analyses of Therapy Outcome - Treatment of Mental Disorders

Meta-Analyses of Therapy Outcome

It

seems, then, that our efforts to evaluate therapies will need to draw on

diverse lines of evidence from many different studies. This creates a new

question for us: How should we put together the evidence? What is the best way

to integrate and summarize the available data? For many investigators, the

answer lies in a statistical technique called meta-analysis.

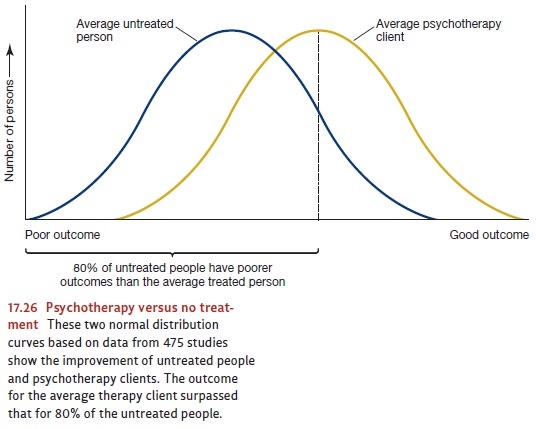

In

one of the earliest analyses of this kind, 475 studies comprising 25,000

patients were reviewed (M. L. Smith et al., 1980; Figure 17.26). In each of

these studies, patients who received some kind of psychotherapy were compared

with a similar group of

patients

who did not receive any. The studies included in this analysis differed in many

respects. One was the kind of psychotherapy used—whether psychodynamic,

human-istic, behavioral, or cognitive. Another factor that varied was the

criterion of improve-ment. In some cases, it was the level of a symptom: the

amount of avoidance that a person with snake phobias eventually showed toward

snakes, the number of washing episodes shown by a patient who washed

compulsively, and so on. In others, it was based on an improvement in

functioning, such as a rise in the grade-point average (GPA) of a student who

was disturbed. In still others, such as studies of patients with depression, it

was an improvement in mood as rated by scales completed by the patient himself

or by knowledgeable outsiders, such as his spouse and children.

Given

all these differences among the studies, combining the results seems

problem-atic, but meta-analysis provides a method. Consider two hypothetical

studies, A and B. Let us say that Study A shows that, after treatment, the

average patient with snake pho-bia can move closer to a snake than the average

patient who received no treatment. Let us also assume that Study B found that

students with depression who received psychotherapy show a greater increase in

GPA than do equivalent students in an untreated control group. On the face of

it, there is no way to average the results of the two studies because they use

completely different units. In the first case, the average effect of

therapy—that is, the difference between the group that received treatment and

the one that did not—is measured in feet (how near the snake the patient will

go); in the second, it is counted in GPA points. But here is the trick provided

by meta-analysis. Let us suppose we find that in Study A, 85% of the treated

patients are able to move closer to the snake than the average untreated

patient. Let us further suppose that in Study B, 75% of the students who

received psychotherapy earn a GPA higher than the average GPA of the untreated

students. Now we can average the scores. To be sure, dis-tance and GPA points

are like apples and oranges and cannot be compared. But the percentage

relationships—in our case, 85 and 75—are comparable. Since this is so, they can

be averaged across different studies.

What,

therefore, do we learn from meta-analyses? The conclusion drawn by averag-ing

across the 475 studies was that the “average person who receives therapy is

better off at the end of it than 80% of the persons who do not”. Later

meta-analyses have used different criteria in selecting studies for inclusion

but yield similar results (see, for example, Wampold et al., 1997). Other

studies found that even months or years after treatment, patients still show

these improvements (Nicholson & Berman, 1983).

Related Topics