Chapter: Psychology: Treatment of Mental Disorders

Current Treatments for Mental Disorders

Current Treatments for Mental Disorders

As

we saw, mental disorders typically involve many factors, some biolog-ical and

some rooted in a person’s circumstances. Different treatments target different

aspects of this network of interrelated causes. Psychological treatments aim to

alter psychological and environmental processes via “talk therapy.” Biomedical

treatments seek to alter underlying biological processes directly, often

through medication or neurosurgery.

For

convenience, we will use this distinction between psychological and biomedical

treatments. However, this shorthand does risk introducing some confusion. If we

focus narrowly on the overt steps in treatment, we can distinguish psychological

approaches (talking to a patient, perhaps leading her to new insights or new

beliefs) from biomedical approaches (perhaps prescribing a pill for the patient

to take twice a day). However, if we broaden our focus, the distinction between

the psychological and the biological becomes less clear-cut. After all,

psychological processes are the prod-ucts of functioning brains—and so changes

in people’s psychology necessarily involve changes in their brain. Hence

psychological treatments have biological effects. Conversely, biomedical

treatments may in many cases work by altering a person’s thought processes or

shifting a person’s mood; for this reason, the biological treatments often need

to be under-stood in “psychological” terms. In either direction, therefore, a

distinction between “psy-chological” and “biological” treatments is somewhat

artificial (Kumari, 2006). In addition, as we will see, contemporary treatments

often combine talk therapy with med-ication, further blurring the line between

psychological and biological treatment.

That

said, it is still useful to distinguish between treatments that emphasize

psycho-logical approaches and those that emphasize biological approaches, and

this leads us to ask: How does a practitioner decide which emphasis is best in

a given case? The answer depends on the illness and our understanding of its

causes. If the illness seems shaped primarily by environmental causes (such as

a hostile family environment) or by the person’s perceptions and beliefs, then

a psychological intervention may be best— helping the person to find ways to

cope with (or change) the environment, or persuad-ing the person to adopt new

beliefs. If the illness seems shaped primarily by some biological dysfunction

(perhaps an overreactive stress response, for example, or a short-age of some

neurotransmitter), then a biomedical intervention may be preferable.

However,

these points are at best rough rules of thumb. In many cases, there may be no

direct correspondence between what triggers a disorder (a specific biological

dysfunction or some life problem) and the nature of the treatment. Some

problems arising from a difficult situation are best treated medically; some

problems arising from a biological dysfunction are best treated with psychotherapy.

In choosing a form of therapy, practitioners must focus on what works, rather

than focusing exclusively on how the disorder arose.

TREATMENT PROVIDERS

We

will have a great deal to say about these two broad emphases in treatment—the

psychological and the biological—and the specific ways that treatment unfolds.

Before we turn to these details, let’s consider the providers and recipients of

these treatments.

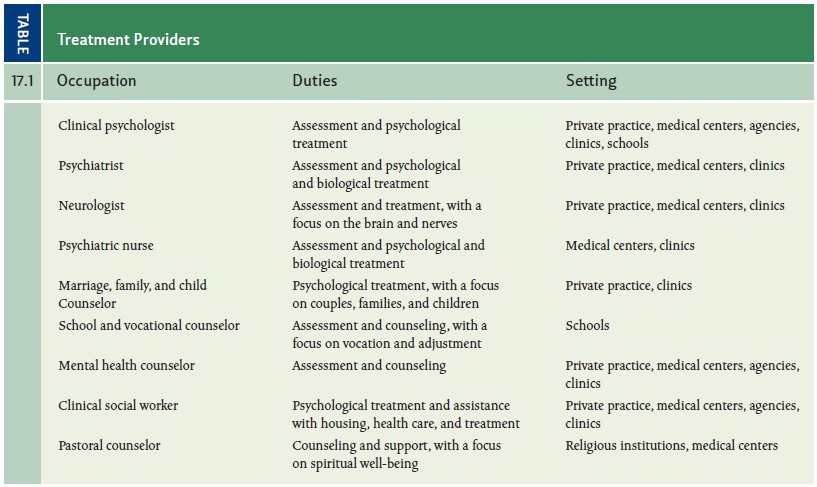

An

extraordinarily wide range of professionals and non-professionals provide

treat-ments for mental disorders. Individuals licensed to provide psychological

treatments include clinical psychologists; psychiatrists; psychiatric nurses;

marriage, family, and child counselors; school and vocational counselors;

mental health counselors; and clinical social workers. Psychological

interventions are also administered by individu-als with varying degrees of

psychological training including pastoral counselors, reli-gious leaders, and

paraprofessionals. A description of each of these treatment providers is given

in Table 17.1.

Surprisingly,

more experienced providers are not always more effective than less experienced

providers (McFall, 2006), and even professional credentials are not

neces-sarily a good predictor of therapeutic success (Blatt, Sanislow, Zuroff,

& Pilkonis, 1996). These findings suggest that who the therapist is, what

he or she does, and how well this matches the patient’s needs may be far more

important than the therapist’s level of experience or the degrees he has

earned. Also crucial is the quality of the rapport

the therapist establishes with the patient—whether the patient respects and

trusts the therapist and feels comfortable in the therapeutic setting. This

rapport, too, is often more important than the therapist’s credentials or type

and degree of training.

Psychological

treatments can be administered either with or without a license (with the

license usually given by the state in which the therapist is practicing). In

clear con-trast, the administration of biomedical treatments does require a

license. Here too, however, there are many different providers, including

psychiatrists, neurologists, and psychiatric nurses. In fact, this list has

been growing, with some jurisdictions now per-mitting “prescription privileges”

for clinical psychologists—that is, allowing people with Ph.D.s to write

prescriptions, a privilege that used to be reserved for people with medical

degrees.

TREATMENT RECIPIENTS

People

seek treatment for a wide variety of reasons. Some seek relief from the pain

and dysfunction associated with a diagnosable mental disorder. Others suffer

with subsyn-dromal disorders—versions

of mental disorders that don’t meet the criteria for diag-nosis but that may

nonetheless cause significant problems (Ratey & Johnson, 1997). Others have

neither a full-fledged nor a sybsyndromal disorder but instead seek help with

feelings of loss, grief, or anxiety, with relationship difficulties, or with

confusion about a major life decision. Still others seek therapy in order to

live happier and more fulfilled lives.

Just

as important is a listing of people who might benefit from therapy but don’t

seek it. Surveys reveal that in the United States, only about 40% of those with

clinically significant disorders (such as depression, anxiety, or substance use

disorders) had received treatment in the past year (Wang, Bergulund, et al.,

2005). Women are more likely than men to seek treatment (Addis & Mahalik,

2003; Wang, Berglund, et al., 2005), and European Americans are more likely to

seek treatment than Asian Americans and Hispanic Americans (Sue & Lam,

2002; Wang, Berglund, et al., 2005).

There

is yet another (and very large) group of people who might benefit from therapy

but cannot get it. According to the World Health Organization, roughly 450

million people worldwide suffer from various mental disorders, and the clear

majority live in developing countries—90% of these people have no access to

treat-ment (Miller, 2006b). Access is also an issue in developed countries.

Many forms of mental illness are more common among the poor, but the poor are

less likely to have insurance coverage that will make the treatment possible

(Wang, Lane, et al., 2005).

CULTURAL CONSIDERATIONS

Some

of the problems just described could—in theory—easily be solved. We could train

more therapists and open more clinics so that treatment would be available to

more people. We could improve insurance coverage or arrange for alternative

forms of financing. These steps, however, would not be sufficient, because

there is still another factor that limits the number of people who can benefit

from therapy: the limited availability of culturally

appropriate therapy and culturally

competent therapists.

A

therapist shows cultural competence

by understanding how a patient’s beliefs, values, and expectations for therapy

are shaped by his cultural background (Sue, 1998). A therapist with this

understanding can modify the goals of therapy to conform to the patient’s values

(Hwang, 2006). For example, many Asian cultures emphasize formal-ity in all

their affairs. Social roles within these cultures are often clearly defined and

tend to be structured largely by age and sex, such that a father’s authority is

rarely chal-lenged within the family. Growing up in such a culture may play an

important part in shaping the values a patient brings to therapy. A therapist

insensitive to these values risks offending the patient and endangering the

therapy. Similarly, a therapy that emphasizes individual autonomy over family

loyalties might inadvertently violate the patient’s cultural traditions and so

be counterproductive.

Cultural

sensitivity also includes other issues. For example, therapists who expect

their patients to take responsibility for making changes in their lives may be

ineffective with patients whose cultural worldview stipulates that important

events are caused by factors such as fate, chance, or powerful others.

Likewise, practitioners who consider psychotherapy a secular endeavor would do

well to remember that in many cultures, any kind of healing must acknowledge

the patient’s spirituality.

Attention

to such cultural differences may also be valuable for another reason: it’s

possible that the Western world can learn something about the treatment of

mental disorders from the cultures in developing countries. For example, the

long-term prog-nosis for schizophrenia is considerably better in developing

countries than it is in the United States (Thara, 2004). Patients with schizophrenia

in India, as one illustration, show far more remission of symptoms and fewer

relapses than patients with schizo-phrenia in the United States and often

recover enough to hold a full-time job, marry, and otherwise lead reasonably

normal lives.

Why

is this? Some suggest that physicians in the United States rely too much on

medication in treating schizophrenia and too little on interventions that

emphasize job training and a supportive social network. The opposite is the

case in India, where med-ication is often not available and

institutionalization is usually not an option. Indeed, it is estimated that

roughly 99% of individuals with schizophrenia live with their fam-ilies in

India, compared with 15 to 25% in the United States (Thara, 2004). Of course,

the style of treatment in the United States is encouraged by many factors,

including families that may want to distance themselves from the patient and

insurance compa-nies that will reimburse patients for psychotropic drugs but

hesitate to pay for social programs.

It

seems, then, that cultural competence needs to be broadly understood. It

includes the need for Western-style practitioners to be alert to the cultural

background (and so to the assumptions, beliefs, and values) of their patients.

But it also includes an open-ness to the possibility that the style of treating

mental illness in other cultures may, for some disorders, be preferable to the

methods used in the developed countries. We need to keep these points in mind

as we turn to a consideration of what the various forms of treatment involve.

Related Topics