Chapter: Psychology: Treatment of Mental Disorders

Psychological Treatments: Behavioral Approaches

Behavioral Approaches

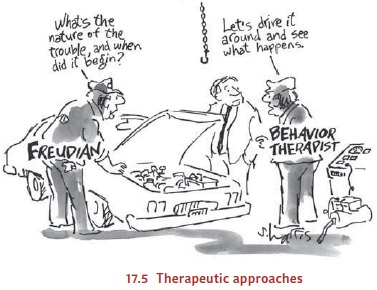

Like

the humanistic therapies, behavior therapies emerged in part as a reaction to

the Freudian tradition of psychoanalysis (Figure 17.5). But while the humanists

regarded psychoanalysis as too mechanis-tic, the behavior theorists,

ironically, offered exactly the opposite crit-icism; they regarded

psychoanalysis as too loose and unscientific.

Behavior

therapists focus on overt behavior rather than uncon-scious thoughts and

wishes, which they regard as hard to define and impossible to observe. The

patient’s behaviors, in other words, are not regarded as “symptoms” through

which one can identify and then cure an underlying illness. Instead, these

therapists view the maladaptive behaviors themselves as the problem to be

solved. These behaviors, in turn, are, from a behaviorist’s perspective, simply

the results of learning—albeit learning that led the person to undesired or

undesirable behaviors.

The

remedy, therefore, involves new learning, in order to replace old habits with

more effective or adaptive ones. For this purpose, the therapeutic procedures

draw on the principles of behavior change that have been well documented in the

laboratory— classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and modelling.

CLASSICAL

CONDITIONING TECHNIQUES

To see how behavior therapy proceeds, consider the treatment for specific phobias (Emmelkamp, 2004; Wolpe & Plaud, 1997). According to behavior therapists, the irra-tional fears that characterize these phobias are simply classically conditioned responses, evoked by stimuli that have become associated with a truly fearful stimulus. The way to treat these phobias, therefore, is to break the con-nection between the phobic stimuli and the associated fears, using a technique akin to the extinction procedures that are effective in diminishing conditioned responses in the laboratory.

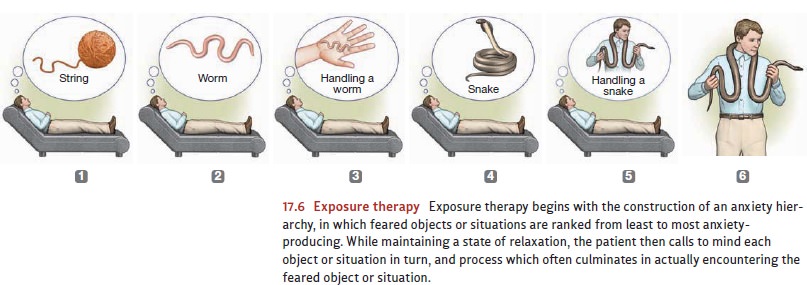

One

early version of this procedure is the technique originally known as systematic

desensitization, now referred to as exposure

therapy. Here, the therapist seeks not only to break the connection between

the phobic stimulus and the fear response but also to create a new connection

between this stimulus and a different response, one that is incompatible with

fear and will therefore displace it (Figure 17.6). The new response is usually

deep muscular relaxation, and the patient is taught a relaxation technique,

typically through meditation-like exercises, before the formal therapy begins.

Then, once the patient has learned to relax deeply on cue, the goal is to

condi-tion this relaxation response to the stimuli that have been evoking fear.

To

begin the therapy, the patient constructs an anxiety hierarchy, in which feared

sit-uations are identified and then ranked from least to most anxiety

provoking. This hier-archy is then used to set the sequence for therapy. The

patient starts out by imagining the first scene in the hierarchy (e.g., being

on the first floor of a tall building) while in a state of deep relaxation. He

will stay with this scene—imagining and relaxing—until he no longer feels any

anxieties. After this, he imagines the next scene (perhaps look-ing out a

fourth-floor window in the building), and this scene, too, is thoroughly

“counter-conditioned,” meaning that the old link between the scene and an

anxiety response is broken, and a new link between the scene and a relaxation

response is forged. The process continues, climbing up the anxiety hierarchy

until the patient finally can imag-ine the most frightening scene of all

(leaning over the railing of the building’s observa-tion tower, more than 100

floors above the ground) and still be able to relax.

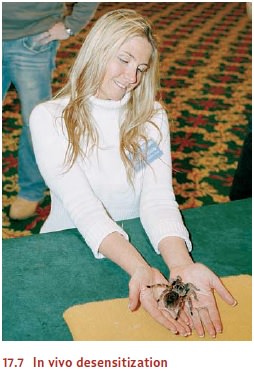

Sometimes

this imagined exposure is sufficient to treat the phobia, but often patients

need to extend the graduated exposure to the real world—for example, actu-ally

visiting a tall building rather than merely thinking about one. This process,

called in vivo desensitization, may

take place with the therapist present or may use guidedhomework assignments

(Figure 17.7; Craske, 1999; Goldfried & Davison, 1994). In addition,

interactive computer graphics now provide yet another option: exposing the

patient to a virtual-reality version of the frightening stimulus, which seems

to be another way to extend and strengthen the desensitization procedure

(Figure 17.8; see, for example, Emmelkamp et al., 2002). However the feared

stimulus or situation is presented, exposure is a key ingredient in therapeutic

success.

OPERANT

CONDITIONING TECHNIQUES

A

second set of behavioral techniques is based on the principles of instrumental

or operant conditioning. These techniques aim to change behavior through

reinforcement by emphasizing the relationship between acts and consequences.

An

example of this approach is the use of token

economies in hospital psychiatric wards. In these settings, patients earn

the tokens through various helpful or healthy behaviors such as making the bed,

being neatly dressed, or performing ward chores. They can then exchange tokens

for desirable items, such as snacks or the chance to watch TV. In this fashion,

the patient is systematically rewarded for producing desirable behaviors and is

not rewarded for producing undesirable ones.

As

in the learning laboratory, the reinforcement contingencies can then be

gradu-ally adjusted, using the process known as shaping. Early on, the patient

might be rein-forced merely for getting out of bed; later, tokens might be

awarded only for getting out of bed and walking to the dining hall. In this

fashion, the patient can be led, step-by-step, to a higher level of

functioning. The overall effects of this technique are that the patients become

less apathetic and the general ward atmosphere is much improved (Higgins,

Williams, & McLaughlin, 2001).

Other

reinforcement procedures can be useful in individual behavior therapy as part

of contingency management. In this

procedure, the person learns that certain behav-iors will be followed by strict

consequences (Craighead, Craighead, Kazdin, & Mahoney, 1994). For example, a

child who is oppositional and defiant can be presented with a menu of “good

behaviors” and “bad behaviors,” with an associated reward and penalty for each.

Being a “good listener” can earn the child the chance to watch a video,

cleaning up her room every day can get her a dessert after dinner, and so

forth, whereas talking back to Mom or making a mess may result in an early

bedtime or a time-out in her room. The idea is not to bribe or coerce the child

but to show her that her actions can change the way people react to her.

Ideally, her changed behavior will result in a more positive social environment

that will eventually make explicit rewards and pun-ishments unnecessary.

These operant techniques have been applied to a number of mental disorders. In one study, parents spent 40 hours a week attempting to shape the behavior of their uncom-municative 3-year-olds who had autism (Lovaas, 1987). By first grade, more than half of the children were functioning successfully in school, and these treatment gains were still evident four years later (McEachin, Smith, & Lovaas, 1993). In a group of 40 compara-ble children who did not receive this intervention, only one child showed comparable improvement by first grade. Others have applied this technique to other serious mental disorders such as mental retardation, with positive results (Reid, Wilson, & Faw, 1991).

MODELING TECHNIQUES

One

last (and powerful) technique for the behavior therapist is modeling, in which someone learns new

skills or changes his behavior by imitating another person (Figure 17.9).

Sometimes, the therapist serves as the model, but this need not be the case.

Therapy with children, for example, may draw on young “assistants” (children roughly

the same age as the child in therapy) who work with the therapist and model the

desired behaviors or skills.

Modeling

is not limited to overt behaviors; a therapist can also model a thought process

or a decision-making strategy. In some forms of therapy, the therapist “thinks

out loud” about commonplace decisions or situations, in this way providing a

model for how the patient should consider similar settings (Kendall, 1990;

Kendall & Braswell, 1985). Likewise, modeling can be used for emotional

responses, so that, for example, the therapist can model fearlessness in the

presence of some phobic stimulus and in this fashion diminish the phobia

(Bandura, 1969, 2001).

Modeling

can also be supported by vicarious reinforcement, a procedure in which the patient

sees the model experience some good outcome after exhibiting the desired

behavior or emotional reaction. Like other forms of reinforcement, vicari-ous

reinforcement seems to increase the likelihood that the person in therapy will

later produce the desired behavior or reaction.

Related Topics