Chapter: Essential Microbiology: Microbial Metabolism

Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis

Photosynthetic organisms are differentiated from all other forms of life by their ability to derive their cellular energy not from chemical nutrients, but from the energy of the Sun itself. A number of different microbial types are able to carry out photosynthesis, which we can regard as having two distinct forms:

· oxygenic photosynthesis, in which oxygen is produced; found in algae, cyanobacteria (blue-greens) and also green plants

· anoxygenic photosynthesis, in which oxygen is not generated; found in the purple and green photosynthetic bacteria.

Both forms of photosynthesis are dependent on a form of the pigment chlorophyll, sim-ilar, but not identical, to the chlorophyll found in green plants. We might at this point mention that there is a third method of phototrophic growth, quite distinct from the other two in that chlorophyll plays no role. This form, which is found in halophilic mem-bers of the Archaea, uses instead a pigment called bacteriorhodopsin, similar in structure and function to the rhodopsin found in the retina of animals. In view of the fact that carbon dioxide is not fixed by this mechanism, and no form of chlorophyll is involved, it does not qualify to be described as photosynthesis by some definitions.

The reactions that make up photosynthesis fall into two distinct phases: in the ‘light’reactions, light energy is trapped and some of it conserved as ATP, and in the ‘dark’ reactions the energy in the ATP is used to drive the synthesis of carbohydrate by thereduction of carbon dioxide.

In the description of photosynthesis that follows, we shall discuss first the reactions of oxygenic photosynthesis, and then consider how these are modified in the anoxygenic form.

Oxygenic photosynthesis

The overall process of oxygenic photosynthesis can be summarised by the equation:

6CO2 + 6H2O -- > C6H12O6 + 6O2

You will perhaps have noticed that the equation is in essence the reverse of the one we saw earlier when discussing aerobic respiration. In fact, the equation above is not strictly accurate, since it is known that all the oxygen is derived from water. It is therefore necessary to rebalance the equation thus:

6CO2+ 12H2O −→ C6H12O6+ 6O2+ 6H2O

Unlike the metabolic reactions we have encountered so far, this reaction requires an input of energy, so the value of DG is positive rather than negative.

Where does photosynthesis take place?

In photosynthetic eucaryotes, photosynthesis takes place in specialised organelles, the chloroplasts. The light-gathering pigments are located on the stacks of flattenedthylakoid membranes, while the dark reactions occurwithin the stroma (see Figure 3.15). The light reactions of cyanobacteria also take place on structures called thy-lakoids; however, since procaryotic cells do not possess chloroplasts, these exist free in the cytoplasm. Their sur-face is studded with knob-like phycobilisomes, which contain unique accessory pigments called phycobilins.

‘Light’ reactions

The light reactions result in:

· splitting of water to release O2 (photolysis)

· reduction of NADP+ to NADPH

· synthesis of ATP.

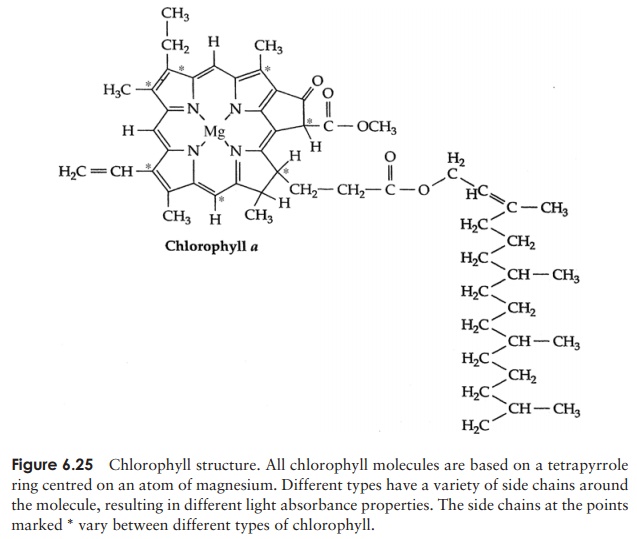

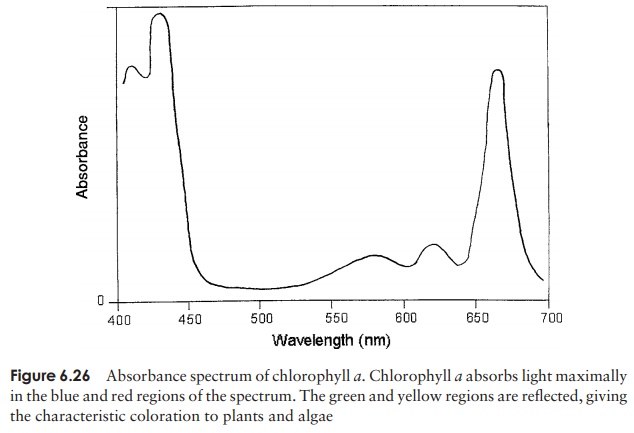

This first stage of photosynthesis is dependent on the ability of chlorophyll to absorb photons of light. Ab-sorption of light causes a rearrangement of the electrons in the chlorophyll, so that the molecule attains an ‘ex-cited’ state. Chlorophyll belongs to a class of organic compounds called tetrapyrroles, centred on a magnesium atom (Figure 6.25); a hydrophobic sidechain allows the chlorophyll to embed itself in the thylakoid membrane where photo-synthetic reactions take place. Several variants of the chlorophyll molecule exist, which differ slightly in their structure and the wavelengths of light they absorb. In organisms carrying out oxygenic photosynthesis, chlorophylla and b predominate, while various bacteriochlorophylls operate in the anoxygenic phototrophs. Chlorophyll a absorbslight in the red and blue parts of the spectrum and reflects or transmits the green part (Figure 6.26) thus cells containing chlorophyll a appear green (unless masked by another pigment). Although other pigments are capable of absorbing light, only chlorophyll is able to pass the excited electrons via a series of electron acceptors/donors to convert NADP+ to its reduced form, NADPH. Associated with chlorophyll are several acces-sory pigments such as carotenoids or phycobilins (in cyanobacteria) with their ownabsorbance characteristics. They absorb light and transfer the energy to chlorophyll, enabling the organism to utilise light from a broader range of wavelengths.

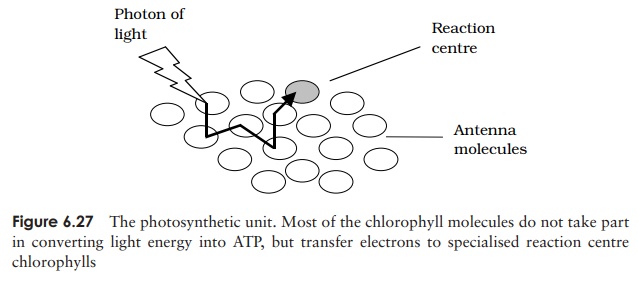

The light-gathering process occurs in collections of hundreds of pigment molecules known as photosynthetic units. Most of these act as antenna molecules that absorb photons of radiant light. A large number of antenna molecules ‘funnel’ light towards a single reaction centre, allowing an organism to operate efficiently even at reduced light intensities. Following excitation of the chlorophyll molecule by a photon of light, an

electron is transferred from one antenna to another, eventually reaching a specialised chlorophyll molecule in a pigment/protein complex called a reaction cen-tre (Figure 6.27). There are two forms of this specialchlorophyll, which absorb light maximally at different wavelengths, 680 nm and 700 nm. These are the starting

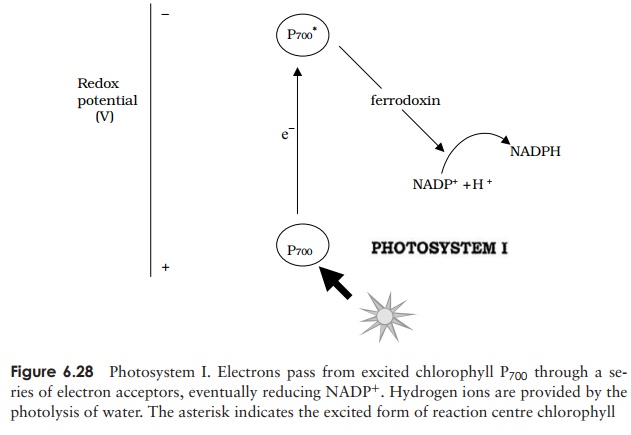

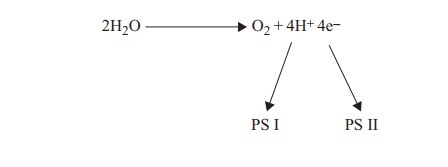

The reactions of photosystem I are responsible for the reduction of NADP+ (Fig-ure 6.28). In its excited state, the chlorophyll molecule has a negative redox potential and sufficient energy to donate an excited electron to an acceptor molecule called ferre-doxin. This is an electron carrier capable of existing in oxidised and reduced forms, likethose we encountered in the electron transport chain of aerobic respiration. From here, the electron is passed through a series of successively less electronegative electron carri-ers until NADP+ acts as the terminal electron acceptor, becoming reduced to NADPH. The hydrogen ions necessary for this are derived from the splitting of water . In order for NADP+ to become reduced as described above, the chlorophyll P700 must receive a constant supply of electrons. There are two ways in which this may be done: the first involves photosystem II. It is here that water is cleaved to produce oxygen in a process involving a light-sensitive enzyme:

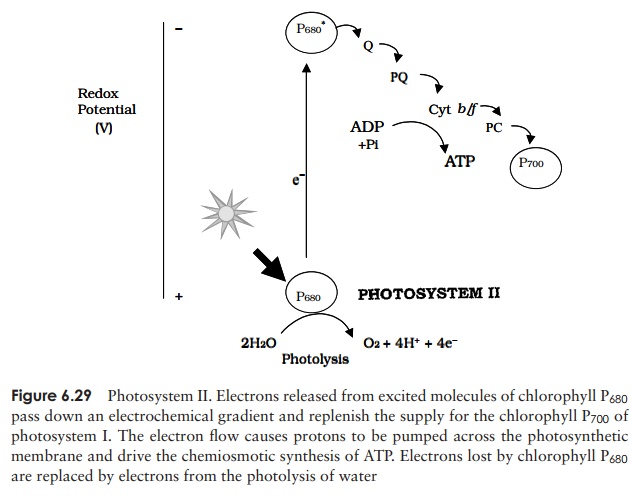

Chlorophyll P680 of photosystem II absorbs a photon of light, and is raised to an ex-cited state, causing an electron to be released down an electrochemical gradient via carrier molecules as described above (Figure 6.29). The terminal electron acceptor for photosystem II is the chlorophyll P700 of photosystem I. The electron flow during this process releases sufficient energy to drive the synthesis of ATP. This process of photophosphorylationoccurs by means of a chemiosmotic mechanism similar to that involved in the electron transport chain of aerobic respiration.

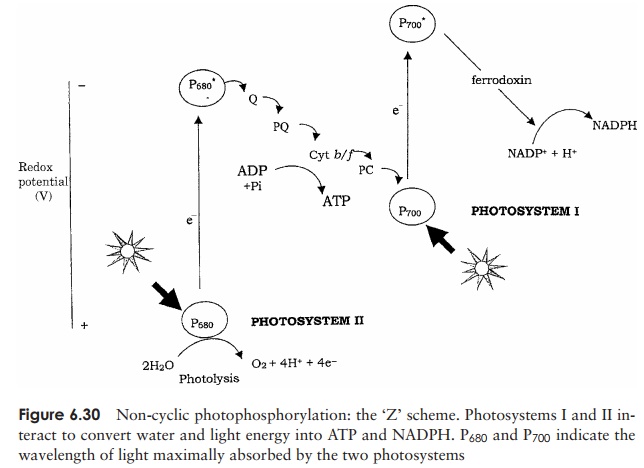

When we look at the way the two photosystems combine to produce ATP and NADPH from light energy and water, it is easy to see why this is sometimes known as the ‘Z’ scheme (Figure 6.30). Only by having the two photosystems operating in series and at different energy levels can sufficient energy be generated to extract an electron from water on the one hand and generate ATP and NADPH on the other.

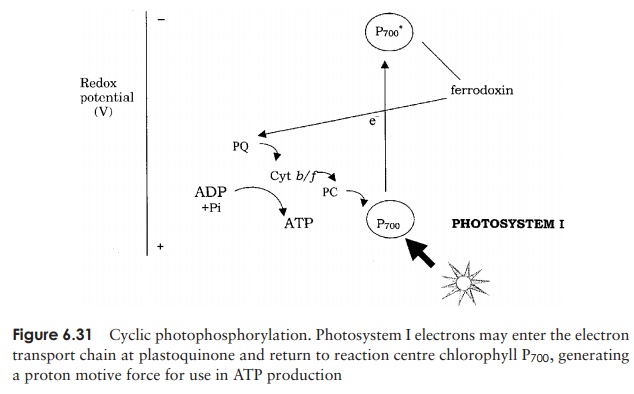

As indicated above, there is an alternative pathway by which the electron supply of the chlorophyll P700 can be replenished. You will recall that in photosystem I, having reached ferredoxin and reduced it, electrons pass through further carriers before reach-ing NADP+ . Sometimes, however, they may take a different route, joining the electron transport chain at plastoquinone (PQ), and generating further ATP (Figure 6.31). The electron ends up back at the P700, so the pathway is termed cyclic photophosphory-lation. Note that because no splitting of water is involved in the cyclic pathway, no oxygen is generated. Also, because the electrons follow a different pathway, NADPH is not produced.

Non-cyclic photophosphorylation: ATP + NADPH + O2 produced

Cyclic photophosphorylation: only ATP produced

As we shall see below, the biosynthetic reactions of the Calvin cycle that follow the light reactions require more ATP than NADPH. This additional ATP is provided by cyclic photophosphorylation.

‘Dark’ reactions

The term ’dark reactions’ is somewhat misleading; while they can take place in the dark, they are dependent upon the ATP and NADPH produced by the light reaction.

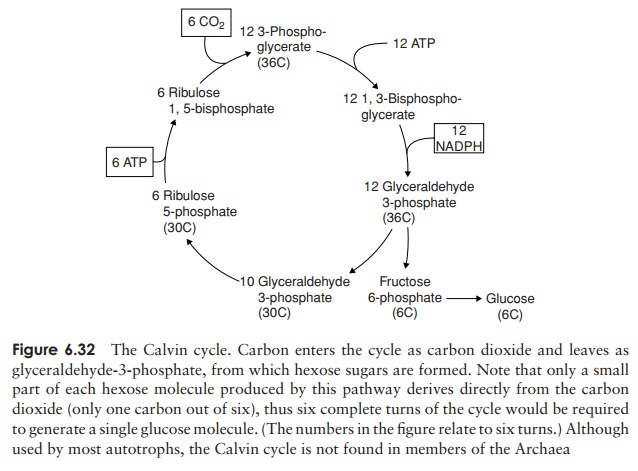

The most widely used mechanism for the incorporation of carbon dioxide into cellular material is the Calvin cycle (Figure 6.32). This is also the means by which many other, non-photosynthetic, autotrophs fix CO2.

Carbon dioxide entering the Calvin cycle combines with a five-carbon compound called ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate to form two molecules of 3-phosphoglycerate via a transient six-carbon intermediate (not shown). The enzyme responsible for this fixa-tion of CO2 is called ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase (rubisco), and it is the most abundant protein in the natural world. The 3-phosphoglycerate is then reduced to give glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3-P), in a process that uses both ATP and NADPH from the light reaction. By a series of reactions that are essentially the reverse of the opening steps of glycolysis, some of this G3-P is converted to glucose. The remaining steps of the Calvin cycle are concerned with regenerating the five-carbon ribulose-5-phosphate. We can summarise the incorporation of CO2 into glucose as:

6CO2+ 18ATP + 12NADPH + 2H++ 12H2O → C6H12O6+ 18ADP +18Pi + 12NADP+

Related Topics