Chapter: Essential Microbiology: Microbial Metabolism

Fermentation

Fermentation

We turn now to the fate of pyruvate when oxygen is not available for aerobic respira-tion to take place. Microorganisms are able, by means of fermentation, to oxidise the pyruvate incompletely to a variety of end products.

It is worth spending a moment defining the word fermentation. The term can cause some confusion to students, as it has come to have different meanings in different contexts. In everyday parlance, it is understood to mean simply alcohol production, while in an industrial context it generally means any large scale microbial process such as beer or antibiotic production, which may be aerobic or anaerobic. To the microbiologist, the meaning is more precise:a microbial process by which an organic substrate (usually a carbohydrate) is broken down without the involvement of oxygen or an electron transport chain, generating energy by substrate-level phosphorylation.

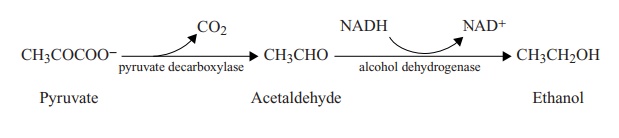

Two common fermentation pathways result in the production of respectively lactic acid and ethanol. Both are extremely important in the food and drink industries. Alcoholic fermentation, which is more common in yeasts than in bacteria, results in pyruvate being oxidised via the intermediate compound acetaldehyde to ethanol.

Electrons pass from the reduced coenzyme NADH to acetaldehyde, which acts as an electron acceptor, and NAD+ is thereby regenerated for use in the glycolytic pathway. No further ATP is generated during these reactions, so the only ATP generated in the fermentation of a molecule such as glucose is that produced by the glycolysis steps. Thus, in contrast to aerobic respiration, which generates 38 molecules of ATP per molecule of glucose, fermentation is a very inefficient process, producing just two. Note that all the ATP produced by any fermentation is due to substrate-level phosphorylation, and does not involve an electron transport chain.

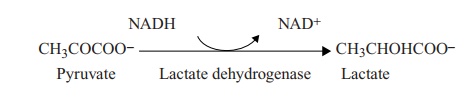

A variety of microorganisms carry out lactic acid fermentation. Some, such as Strep-tococcus and Lactobacillus, produce lactic acid as the only end product; this is referredto as homolactic fermentation.

Certain other microorganisms, such as Leuconostoc, generate additional products such as alcohols and acids in a process called heterolactic fermentation.

In both alcohol and lactic acid fermentation, the two NADH molecules produced per molecule of glucose have been reoxidised to NAD+ , ready to re-enter the glycolytic pathway.

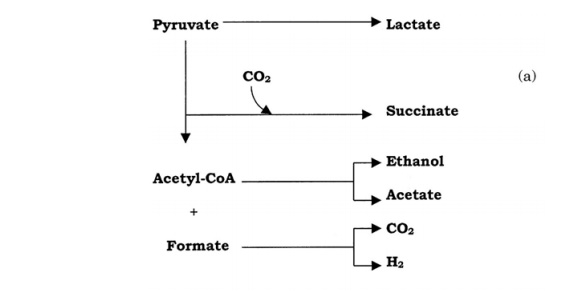

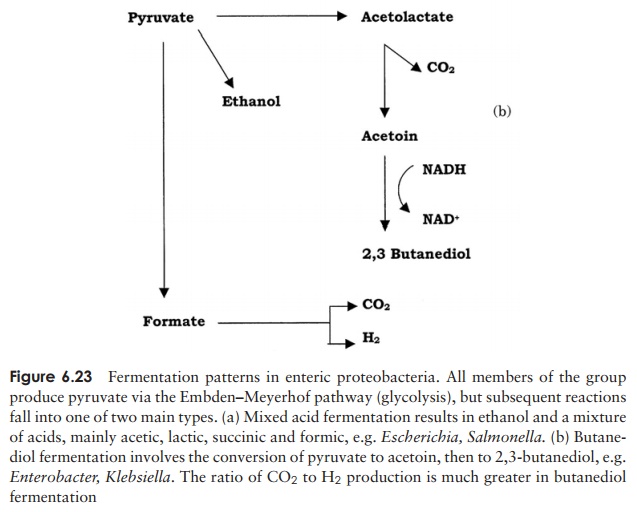

Other types of fermentation

Members of the enteric bacteria metabolise pyruvate to a variety of organic compounds; two principal pathways are involved, both of them involving formic acid. In mixed acidfermentation, pyruvate is reduced by the NADH to give succinic, formic and acetic acids,together with ethanol (Figure 6.23a). Escherichia, Shigella and Salmonellabelong to this group. Other enteric bacteria, such as Klebsiella and Enterobacter, carry out 2,3-butanediol fermentation. In this, the products are not acidic, and include an intermediate called acetoin. Much more CO2 is produced per molecule of glucose than in mixed acid fermentation (Figure 6.23b). The end products of the two types of fermentation provide a useful diagnostic test for the identification of unknown enteric bacteria.

Related Topics