Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Fish genetics

Pelagic larval duration and population structure - Fish genetics

Pelagic larval duration and population structure

The low level of population structure in marine fishes is a consequence of high dispersal, although other factors such as large population size may contribute to this trend. With few hard barriers in the ocean, and with pelagic larval periods ranging from a few days to 2 years, marine fishes have tremendous potential for dispersal. However, recent modeling and field work have disputed the conclusion that all coastal marine fishes have large “open” populations (Cowen 2002; Mora & Sale 2002; Swearer et al. 2002;Jones et al. 2005). Mark/recapture studies have demonstrated a surprising retention of larvae near their region of origin. Taylor and Hellberg (2005) show genetic partitions on a scale of tens of kilometers in the Caribbean cleaner gobies (Elacatinus spp.), and as noted in the molecular ecology section above, marine mouth-brooders (family Apogonidae) and pouch-brooders (family Syngnathidae) can have very strong population differences due to limited dispersal as both young and adults (Lourie et al. 2005). On the other hand, some apparently sedentary reef fishes can have little population structure across huge swaths of ocean. The pygmy angelfishes (genusCentropyge) show no structure across the central and West Pacific, and across the entire tropical West Atlantic, apparently due to oceanic dispersal of larvae (Bowen et al. 2006a; Schultz et al. 2007). Some fishes may transform from larvae to juveniles but remain in the open ocean for an extended period, as is apparently the case for soldierfishes (genus Myripristis), which show no population structure across the entire tropical Atlantic, and across the central and West Pacific (Bowen et al. 2006b; Craig et al. 2007).

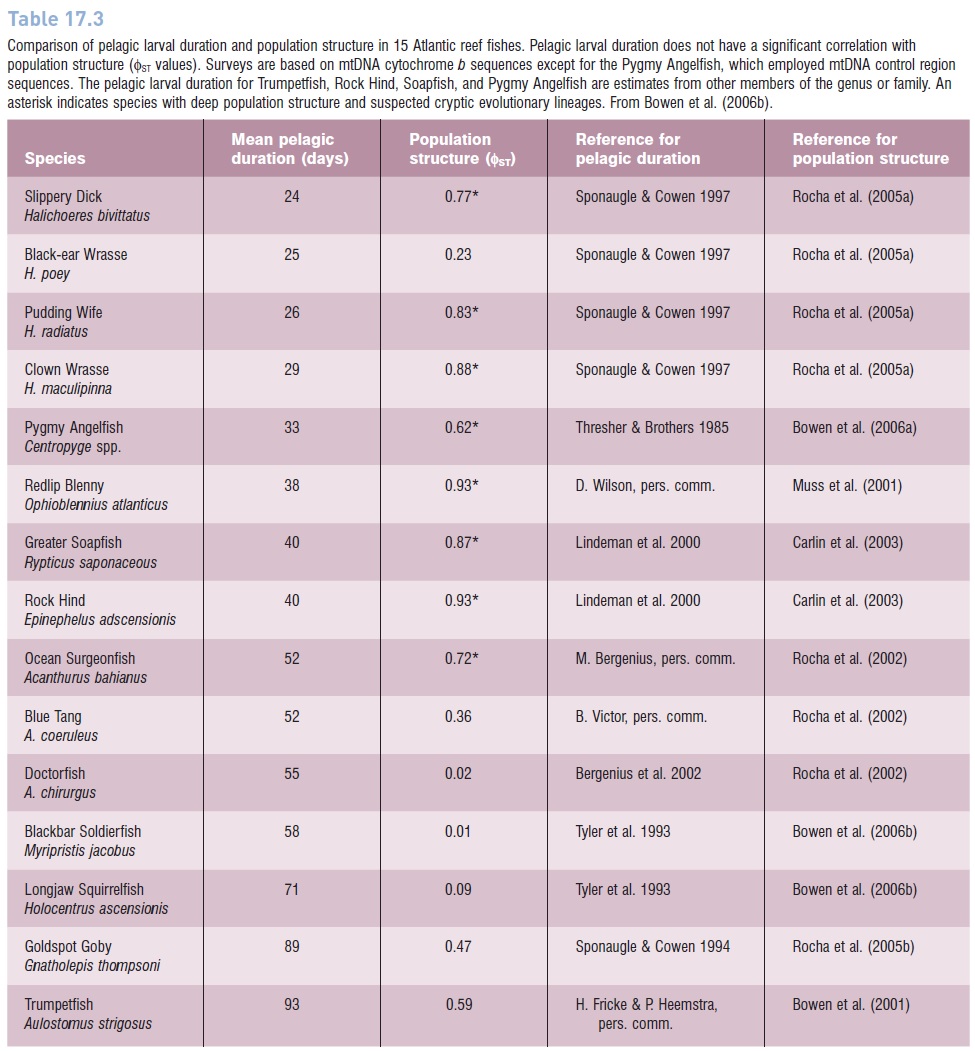

Several researchers have made multispecies comparisons of pelagic larval duration (PLD) and population structure (measured with F statistics) to forge the intuitive links between PLD, dispersal, and population structure. It seems obvious that if larvae are drifting with oceanic currents, the longer pelagic duration will yield greater dispersal and less population structure. Indeed the first comparisons of pelagic larval duration and genetic connectivity in marine fishes supported this connection. Waples (1987) surveyed 10 species in the eastern Pacific, Doherty et al. (1995) surveyed seven species on the Great Barrier Reef, and both of these allozyme studies found a correlation between PLD and population genetic structure. However, subsequent studies have not replicated this correlation. In surveys of eight reef fishes in the Caribbean Sea (Shulman & Bermingham 1995), eight species on the Great Barrier Reef (Bay et al. 2006), and 15 reef species in the tropical Atlantic (Bowen et al. 2006b), no significant correlation was observed between PLD and population genetic structure (Table 17.3).

What can explain these contradictory results? The explanation likely includes at least three components:

1 The two studies that report a significant correlation between PLD and genetic connectivity (Waples 1987; Doherty et al. 1995) are anchored by species that lack a pelagic dispersive stage, and the significant relationship is weakened or lost without these cases (Bohonak 1999; Bay et al. 2006). Therefore it appears that PLD has some influence on population structure, as is most apparent in the fishes with very short or very long pelagic stages. However, other life history factors such as habitat specificity and larval behavior (see below) are involved as well (Riginos & Victor 2001; Rocha et al. 2002).

2 Fish larvae are not “drift bottles” at the mercy of ocean currents. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that they can swim against currents, navigate, and in some cases remain in the vicinity of appropriate juvenile habitats (Leis & Carson-Ewart 2000b; Sweareret al. 2002).

3 Most of the comparisons are among reef fishes, a category that is not cohesive in any phylogenetic or taxonomic sense. The reef fishes includes lineages that diverged from one another 100+million years before present (Bellwood & Wainwright 2002). Such relatively great age of separation in other taxonomic groups would mandate comparisons between wolves and baboons, for example. Marine fishes are too diverse to expect a simple relationship between larval duration and dispersal.

Related Topics