Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Pediatric Anesthesia

Pediatric Anesthetic Techniques: Tracheal Intubation

Tracheal Intubation

One hundred percent oxygen should be adminis-tered prior to intubation

to increase patient safety during the obligatory period of apnea prior to and

during intubation. For awake intubations in neonates or infants, adequate

pre-oxygenation and continued oxygen insufflation dur-ing laryngoscopy (eg,

Oxyscope) may help prevent hypoxemia.

The infant’s prominent occiput tends to place

the head in a flexed position prior to intubation. This is easily corrected by

slightly elevating the shoulders with towels and placing the head on a

doughnut-shaped pillow. In older children, promi-nent tonsillar tissue can

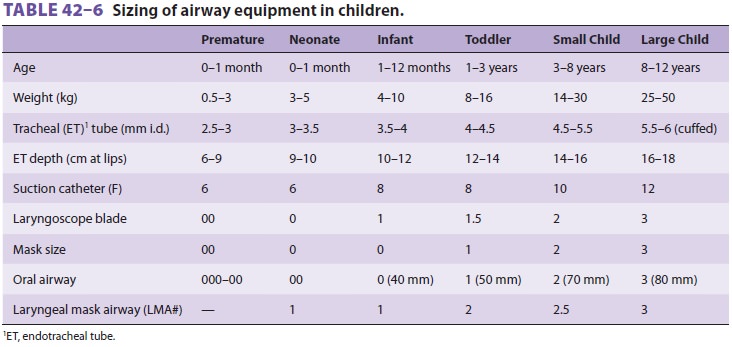

obstruct visualization of the larynx. Straight laryngoscope blades aid

intuba-tion of the anterior larynx in neonates, infants, and young children

(Table 42–6). Endotracheal tubes that pass through the glottis may still

impinge upon the cricoid cartilage, which is the narrowest point of the airway

in children younger than 5 years of age. Mucosal trauma from trying to force a

tube through the cricoid cartilage can cause postoperative edema, stridor,

croup, and airway obstruction.

The appropriate diameter inside the endotra-cheal tube can be estimated

by a formula based on age:

4 + Age/4 = Tube diameter (in mm)

For example, a 4-year-old child would be

pre-dicted to require a 5-mm tube. This formula provides only a rough

guideline, however. Exceptions include premature neonates (2.5–3 mm tube) and

full-term neonates (3–3.5 mm tube). Alternatively, the practi-tioner can

remember that a newborn takes a 2.5- or 3-mm tube, and a 5-year-old takes a

5-mm tube. It should not be that difficult to identify which of the three sizes

of tube between 3 and 5 mm is required in small children. In larger children,

small (5–6 mm) cuffed tubes can be used either with or without the cuff

inflated to minimize the need for precise sizing. Endotracheal tubes 0.5 mm

larger and smaller than predicted should be readily available in or on the

anesthetic cart. Uncuffed endotracheal tubes tradi-tionally have been selected

for children aged 5 years or younger to decrease the risk of postintubation

croup, but many anesthesiologists no longer use size 4.0 or larger uncuffed

tubes. The leak test will mini-mize the likelihood that an excessively large

tube has been inserted. Correct tube size is confirmed by easy passage into the

larynx and the development of a gas leak at 15–20 cm H 2O pressure for an uncuffed tube. No leak

indicates an oversized tube that should be replaced to prevent postoperative

edema, whereas an excessive leak may preclude adequate ventilation and

contaminate the operating room with anesthetic gases. As noted above, many

clinicians use a down-sized cuffed tube with the cuff completely deflated in

younger patients at high risk for aspiration; minimal inflation of the cuff can

stop any air leak. There is also a formula to estimate endotracheal length:

12 + Age/2 = Length of tube (in cm)

Again, this formula provides only a guideline, and the result must be

confirmed by auscultation and clinical judgment. To avoid endobronchial

intu-bation, the tip of the endotracheal tube should pass only 1–2 cm beyond an

infant’s glottis. We favor an alternative approach: to intentionally place the

tip of the endotracheal tube into the right mainstem bron-chus and then

withdraw it until breath sounds are equal over both lung fields.

Related Topics