Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Pediatric Anesthesia

Pediatric Anesthetic Techniques: Maintenance

Maintenance

Ventilation is almost always controlled

during anesthesia of neonates and infants with a conven-tional semiclosed

circle system. During spontane-ous ventilation, even the low resistance of a

circle system can become a significant obstacle for a sick neonate to overcome.

Unidirectional valves, breath-ing tubes, and carbon dioxide absorbers account

for most of this resistance. For patients weighing less than 10 kg, some

anesthesiologists prefer the Mapleson D circuit or the Bain system because of

their low resistance and light weight. Nonetheless, because breathing-circuit

resistance is easily overcome by positive-pressure ventilation, the circle

system can be safely used in patients of all ages if ventilation is controlled.

Monitoring of airway pressure may provide early evidence of obstruction from a

kinked endotracheal tube or accidental advancement of the tube into a main-stem

bronchus.

Many anesthesia ventilators on older machines

are designed for adult patients and cannot reliably provide the reduced tidal

volumes and rapid rates required by neonates and infants. Unintentional

delivery of large tidal volumes to a small child can generate excessive peak

airway pressures and cause barotrauma. The pressure-limited mode, which is

found on nearly all newer anesthesia ventilators, should be used for neonates,

infants, and toddlers. Small tidal volumes can also be manually delivered with

greater ease with a 1-L breathing bag than with a 3-L adult bag. For children

less than 10 kg, ade-quate tidal volumes are achieved with peak inspira-tory

pressures of 15–18 cm H2O. For larger children the volume control ventilation may be used and

tidal volumes may be set at 6–8 mL/kg. Many spi-rometers are less accurate at

lower tidal volumes. In addition, the gas lost in long, compliant adult

breathing circuits becomes large relative to a child’s small tidal volume. For

this reason, pediatric tubing is usually shorter, lighter, and stiffer (less

compli-ant). Nevertheless, one should recall that the dead space contributed by

the tube and circle system consists only of the volume of the distal limb of

the Y-connector and that portion of the endotracheal tube that extends beyond

the airway. In other words, the dead space is unchanged by switching from adult

to pediatric tubing. Condenser humidifiers or heat and moisture exchangers

(HMEs) can add consider-able dead space; depending on the size of the patient,

they either should not be used or an appropriately sized, pediatric HME should

be employed.

Anesthesia can be maintained in pediatric

patients with the same agents as in adults. Some cli-nicians switch to

isoflurane following a sevoflurane induction in the hope of reducing the

likelihood of emergence agitation or postoperative delirium (see above). If

sevoflurane is continued for main-tenance, administration of an opioid (eg,

fentanyl, 1–1.5 mcg/kg) 15–20 min before the end of the procedure can reduce

the incidence of emergence delirium and agitation if the surgical procedure is

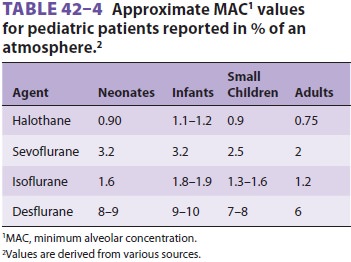

likely to produce postoperative pain. Although the MAC is greater in children

than in adults (see Table 42–4), neonates may be particularly sus-ceptible to

the cardiodepressant effects of general anesthetics. Neonates and sick children

may not tolerate increased concentrations of volatile agents required when the

volatile agent alone is used to maintain good surgical operating conditions.

Related Topics