Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Pediatric Anesthesia

Pediatric Anesthesia: Anatomic & Physiological Development

ANATOMIC & PHYSIOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT

Respiratory System

Compared with older chil-dren and adults, neonates and infants have

weakerintercostal muscles and weaker diaphragms

(due to a paucity of type I fibers) and less efficient ventilation, more

horizontal and pliable ribs, and protuberant abdomens. Respiratory rate is

increased in neonates and gradually falls to adult values by adolescence. Tidal

volume and dead space per kilogram are nearly constant during development. The

presence of fewer, smaller airways produces increased airway resis-tance. The

alveoli are fully mature by

late childhood (about 8 years of age). The

work of breathing is increased and respiratory muscles easily fatigue.

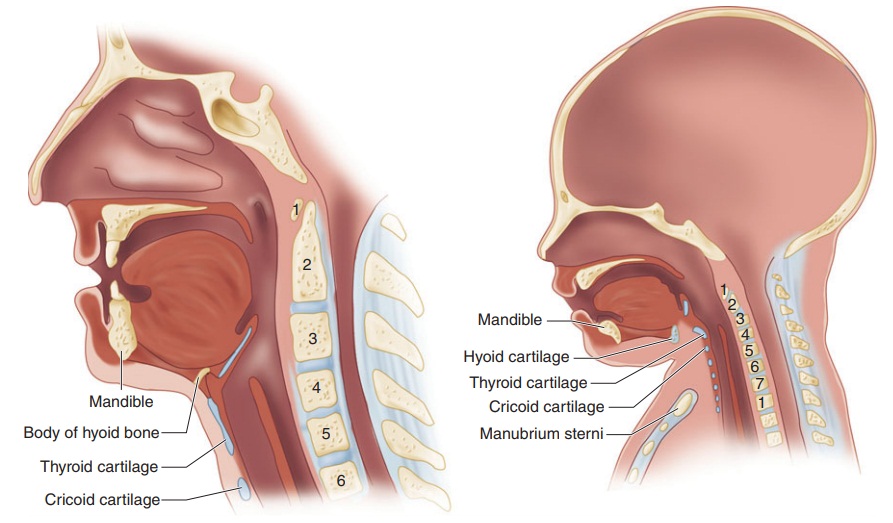

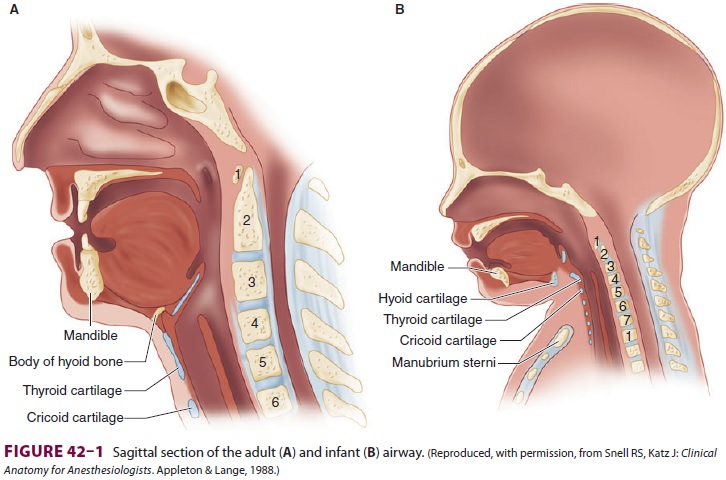

Neonates and infants have fewer and smaller alveoli, reducing lung compliance; in contrast,their cartilaginous rib cage makes their chest wall very compliant. The combination of these two char-acteristics promotes chest wall collapse during inspi-ration and relatively low residual lung volumes at expiration. The resulting decrease in functional residual capacity (FRC) limits oxygen reserves dur-ing periods of apnea (eg, intubation attempts) and readily predisposes neonates and infants to atelecta-sis and hypoxemia. This may be exaggerated by their relatively higher rate of oxygen consumption. Moreover, hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory drives are not well developed in neonates and infants. In fact, unlike in adults, hypoxia and hypercapnia may depress respiration in these patien Neonates and infants have, compared with older children and adults, a proportionately larger head and tongue, narrower nasal pas-sages, an anterior and cephalad larynx (the glottis is at a vertebral level of C4 versus C6 in adults), a longer epiglottis, and a shorter trachea and neck (Figure 42–1). These anatomic features make neo-nates and young infants obligate nasal breathers until about 5 months of age. The cricoid cartilage is the narrowest point of the airway in children younger than 5 years of age; in adults, the narrow-est point is the glottis. One millimeter of mucosal edema will have a proportionately greater effect on gas flow in children because of their smaller tra-cheal diameters.

Cardiovascular System

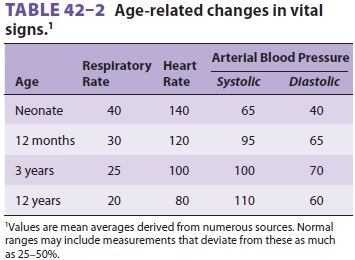

Cardiac stroke volume is relatively fixed by

a noncompliant and immature left ventricle inneonates and infants. The cardiac

output is there-fore very sensitive to changes in heart rate . Although basal

heart rate is greater than in adults (Table 42–2), activation of the para-sympathetic nervous system, anesthetic overdose,

or hypoxia can quickly trigger bradycardia and profound reductions in cardiac

output. Sick infants undergoing emergency or prolonged surgical proce-dures

appear particularly prone to episodes of bra-dycardia that can lead to

hypotension, asystole, and intraoperative death. The sympathetic nervous

sys-tem and baroreceptor reflexes are not fully mature. The infant

cardiovascular system displays a blunted response to exogenous catecholamines.

The imma-ture heart is more sensitive to depression by volatile anesthetics and

to opioid-induced bradycardia. The vascular tree is less able to respond to

hypovolemia with compensatory vasoconstriction. Intravascular volume depletion

in neonates and infants may be signaled by hypotension without tachycardia.

Metabolism & Temperature Regulation

Pediatric patients have a larger surface area per kilo-gram than adults (or a smaller body-mass index). Metabolism and its associated parameters (oxygen consumption, CO2 production, cardiac output, and alveolar ventilation) correlate better with surface area than with weight.Thin skin, low fat content, and a greater sur-face area relative to weight promote greaterheat loss to the environment in neonates. This problem is compounded by inadequately warmed operating rooms, prolonged wound exposure, administration of room temperature intravenous or irrigation fluid, and dry anesthetic gases. Of course, there are also effects of anesthetic agents on temper-ature regulation . Even mild degrees of hypothermia can cause perioperative problems, including delayed awakening from anesthesia, car-diac irritability, respiratory depression, increased pulmonary vascular resistance, and altered responses to anesthetics, neuromuscular blockers, and other agents. The more important mechanisms for heat production in neonates are nonshivering thermogenesis by metabolism of brown fat and shifting of hepatic oxidative phosphorylation to more thermogenic pathway. Yet, metabolism of brown fat is severely limited in premature infants and in sick neonates who are deficient in fat stores. Furthermore, volatile anesthetics inhibit thermo-genesis in brown adipocytes.

Renal & Gastrointestinal Function

Kidney function approaches normal values (cor-rected for size) by 6

months of age, but this may be delayed until the child is 2 years old.

Premature neonates often demonstrate multiple forms of renal immaturity,

including decreased creatinine clearance; impaired sodium retention, impaired glucose

excretion, and impaired bicarbonate reab-sorption; and reduced diluting and

concentrating ability. These abnormalities underscore the impor-tance of

appropriate fluid administration in the early days of life.

Neonates also have a relatively increased inci-dence of gastroesophageal

reflux. The immature liver conjugates drugs and other molecules less read-ily

early in life.

Glucose Homeostasis

Neonates have relatively reduced glycogen stores, predisposing them to

hypoglycemia. Impaired glu-cose excretion by the kidneys may partially offset

this tendency. In general, neonates at greatest risk for hypoglycemia are

either premature or small for gestational age, receiving hyperalimentation, and

the offspring of diabetic mothers.

Related Topics