Chapter: Surgical Pathology Dissection : The Digestive System

Pancreas: Surgical Pathology Dissection

Pancreas

The

pancreas can intimidate even the most expe-rienced pathologist. The complexity

of the anat-omy of the pancreas and the importance of a good dissection in

establishing the correct diag-nosis make the arrival of a resected pancreas in

the surgical pathology laboratory a particularly stressful event. This stress

can, however, be greatly reduced if you familiarize yourself with a few basic

aspects of the anatomy of the pan-creas, and if you take a simple, logical

approach to your dissection.

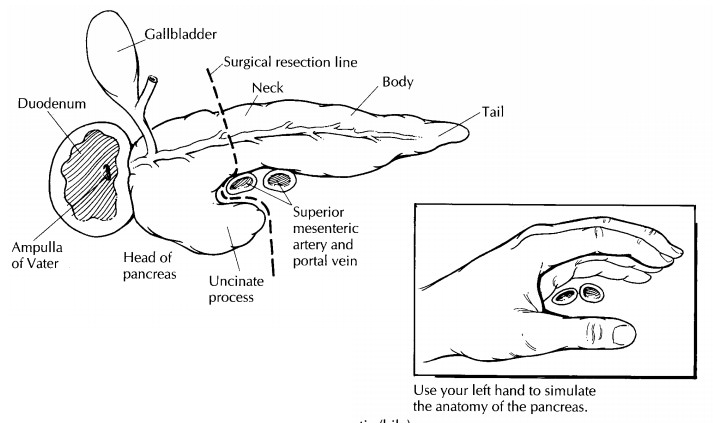

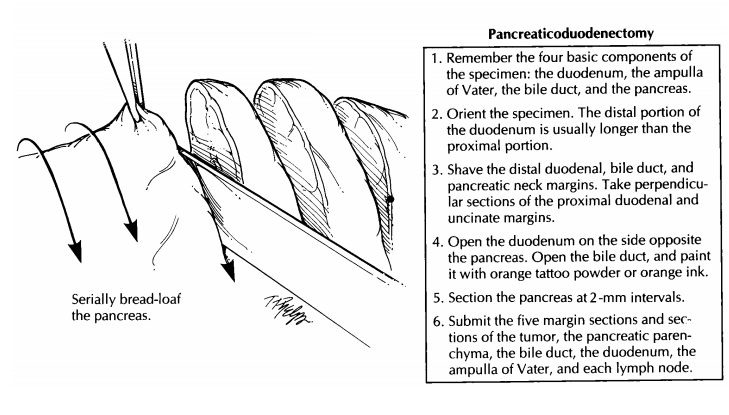

Pancreaticoduodenectomies

The

Whipple procedure (pancreaticoduodenec-tomy) has emerged as an effective and

safe treat-ment for neoplasms of the head of the pancreas, duodenum, distal

common bile duct, and am-pulla of Vater. The orientation of these specimens can

be greatly simplified if you remember that the specimen is composed of four

basic compo-nents: (1) the duodenum, (2) the ampulla of Vater, (3) the bile

duct, and (4) the pancreas.

Begin by

orienting the duodenum: Two fea-tures of the duodenum can be used to identify

its proximal and distal ends. First, the free proxi-mal end is almost always

shorter than the free distal segment of the resected duodenum. Second, a small

part of the stomach is occasion-ally attached to the proximal end. Next,

identify the bile duct. As illustrated, the common bile duct can be recognized by

its greenish color and characteristic tubular appearance. Also, if the

gallbladder is present, use the insertion of the cystic duct to identify the

common bile duct. The remaining components of the pancreas can be identified

using the duodenum and bile duct as guides. The pancreas itself sits at the

base of the junction of the bile duct and duodenum. The head of the pancreas

sits within the duodenal C loop. The pancreatic neck margin can be recog-nized

as the cut oval pancreatic surface with a central duct. Although the uncinate

process of the pancreas is more difficult to identify, it can be visualized if

you keep the anatomy of the pancreas in mind. As illustrated, the pancreas sits

like a slightly curled hand enveloping the superior mesenteric artery and the

portal vein. The thumb of the curled hand corresponds to the uncinate process

of the pancreas and the flat fingers to the neck, body, and tail. Although the

superior mesenteric vessels are not present in the resected specimen, remember

that they were dissected from the pancreas right at the groove between the

thumb and index finger.

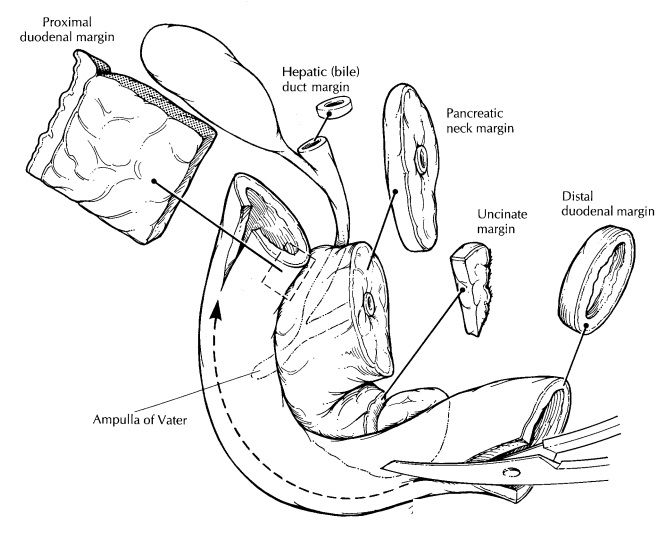

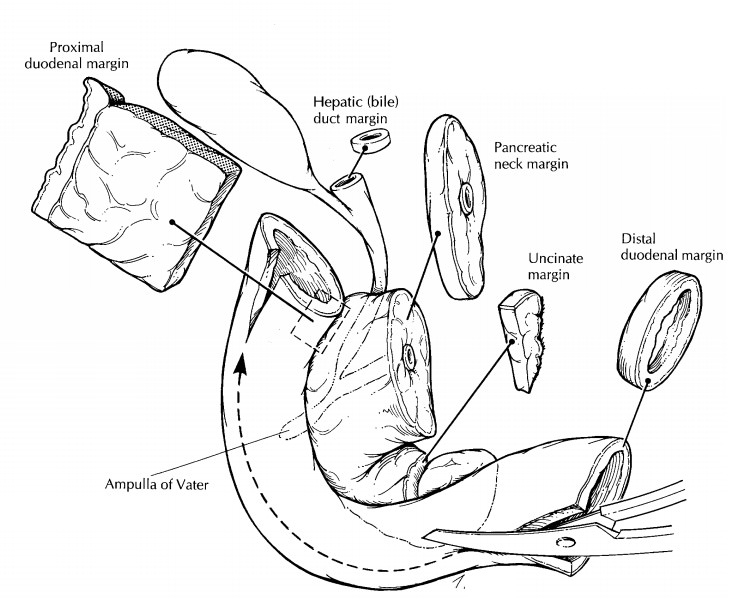

After

the major external landmarks have been identified, measure the dimensions of

each, and ink the surface of the pancreas and the proximal and distal duodenal

margins. Begin the dissection by opening the duodenum along the side oppo-site

the pancreas. Look for and document any duodenal masses, ulcers, or areas of

puckering of the duodenal mucosa. Before cutting the speci-men any further,

submit sections of the margins. These should include: (1) a shave section of

the bile duct margin; (2) a shave section of the pan-creatic neck margin; (3) a

perpendicular section of the uncinate margin taken to include the vascular

groove; (4) a perpendicular section from the prox-imal duodenal margin; and (5)

a shave section from the distal duodenal margin. Next, using a pair of

scissors, open the common bile duct. Because the extrapancreatic (proximal)

portion of the duct is usually dilated, you may find it easier

Distal Pancreatectomies

Distal pancreatectomies are much easier to handle than are pancreaticoduodenectomies. The anatomy is simple, and there are fewer margins to sample. First, find the proximal and distal ends of the pancreas. The spleen helps identify the distal aspect of the gland, and the cut surface of the pancreas is the proximal end. Next, weigh and measure the specimen, and submit a shave section of the proximal pancreatic margin. Ink the surface of the gland, and then bread-loaf it into 2-mm slices using a long sharp knife. These slices should be made perpendicular to the long axis of the gland. Examine the pancreatic parenchyma carefully, paying particular attention to the pancreatic duct. Is the duct dilated or stenotic? Are there any masses or calculi in it? What is the consistency of any fluid in the duct? Note the size, location, and gross appearance of any masses. Submit representative sections of any tumors and of the pancreatic parenchyma. Examine the peripancreatic soft tissues for lymph nodes, note their gross appearance, and submit a representative section of each. If the spleen is present, weigh it, measure it, section it, and submit representative sections, as described in the discussion of the spleen.

Like the

pancreaticoduodenectomy specimen, your final report should document the

presence or absence of a neoplasm; the type, grade, and size of the tumor; the

status of the margins; any lymph node metastases; and the presence or absence

of vascular, perineural, and soft tissue invasion.

Cystic Tumors

Cystic

masses in the pancreas should be handled as described above. In addition,

remember to do the following: (1) Describe the character of the cyst contents.

Is the fluid clear or cloudy? Is it serous, mucinous, necrotic or bloody? A

good description of the cyst contents can be invaluable in determining the

tumor type. (2) Document whether the cyst is unilocular or multilocular. How

large are the cysts, and are there any mural nodules? (3) If the cyst is lined

by mucinous epi-thelium, then the entire cyst should be submitted for

histologic diagnosis. Keep in mind that other-wise benign-appearing mucinous

cystic neo-plasms can harbor small invasive cancers. (4) Finally and

importantly, document the relation-ship of the cyst to the pancreatic ducts.

This can be important because intraductal papillary mu-cinous neoplasms, by

definition, involve the duct system, whereas mucinous cystic neoplasms usually

do not.

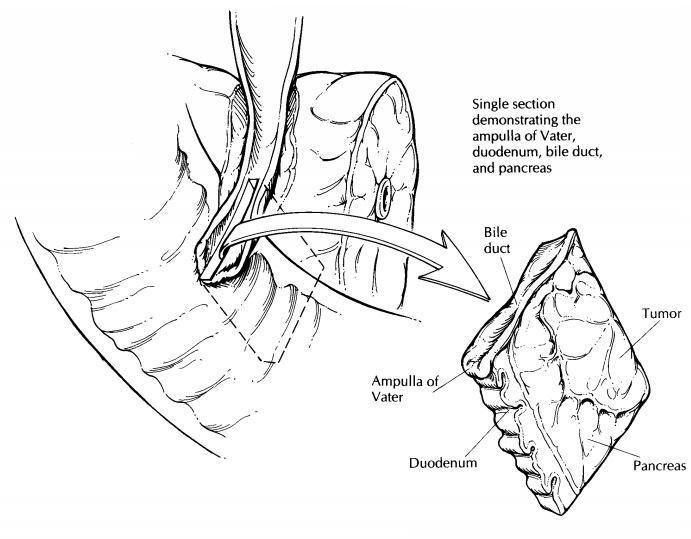

Ampullectomy

The ampulla of Vater is formed by the confluence of the pancreatic and distal common bile ducts as they pass through the wall of the duodenum and open into the duodenal lumen. Small neo-plasms of the ampulla of Vater are occasionally resected in a procedure known as an ampullec-tomy. In these instances the specimen usually consists of a small disk of duodenal tissue about the size of a quarter. The underside of the disk is composed of transected sections of the pancreatic and bile ducts, the disk itself is traversed by the ducts, and the upper surface is lined by duodenal mucosa, in the center of which is the papilla of Vater.

Identify

the bile and pancreatic ducts and submit a shave section of each duct margin.

Next, ink the edges of the disk (the duodenal margins) and the aspects of the

deep margin not sampled when the duct margins were taken. Then simply

bread-loaf the specimen in 2-mm slices along the axis that best demonstrates

the relationship between the tumor and the duodenal margin it most closely

approaches. Document the gross appearance (e.g., papillary, endophytic), size,

and location of any masses; then submit the entire specimen for histologic

evaluation.

Important Issues to Address in Your Surgical Pathology Report on Pancreatic Resections

·

What procedure was performed, and what structures/organs

are present?

·

Is a neoplasm present?

·

What is the probable site of origin of the

tu-mor (bile duct, pancreas, ampulla of Vater, or duodenum)?

·

What is the size of the tumor (in centimeters)?

·

What are the histologic type and grade of the neoplasm?

Is an in situ component identified?

·

Does the tumor extend into the peripancreatic

soft tissues? If so, does it extend anteriorly or posteriorly?

·

Does the tumor infiltrate blood vessels,

lym-phatics, or nerves? Does the tumor extend into the pancreas, duodenum,

ampulla of Vater, common bile duct, or spleen?

·

Does the tumor involve any of the margins

(pancreatic neck, uncinate, bile duct, soft tissue, and proximal and distal

duodenal)?

·

Does the tumor involve regional lymph nodes?

Include the number of nodes examined and the number of nodes involved.

·

Do the non-neoplastic portions of the pancreas

and duodenum show any pathology?

Related Topics