Chapter: Surgical Pathology Dissection : The Digestive System

Non-Neoplastic Intestinal Disease: Surgical Pathology Dissection

Non-Neoplastic Intestinal Disease

Small Biopsies

Proper

tissue orientation is a critical part of the histologic evaluation of biopsies

of the gastroin-testinal tract. Tissue orientation is a two-step pro-cess that

involves the coordinated actions of the endoscopist and the histotechnologist.

The en-doscopist should mount the biopsy mucosal-side up on an appropriate

solid surface (e.g., filter paper) and place it in fixative. This first step

should be done immediately, in the endoscopy suite, so that the specimen does

not dry out en route to the surgical pathology laboratory. The

histotechnologist can then embed and cut the biopsy specimen perpendicular to

the mounting surface. If the specimen is free-floating, great care must be taken

to identify the mucosal surface for proper embedding. Multiple sections should

be cut from each tissue block for histologic evalua-tion. Step sections are

preferred to serial sections so that intervening unstained sections are

avail-able for special stains as needed.

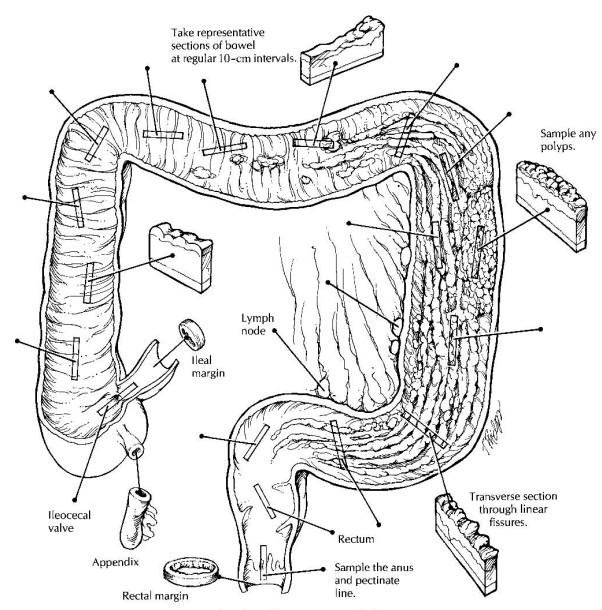

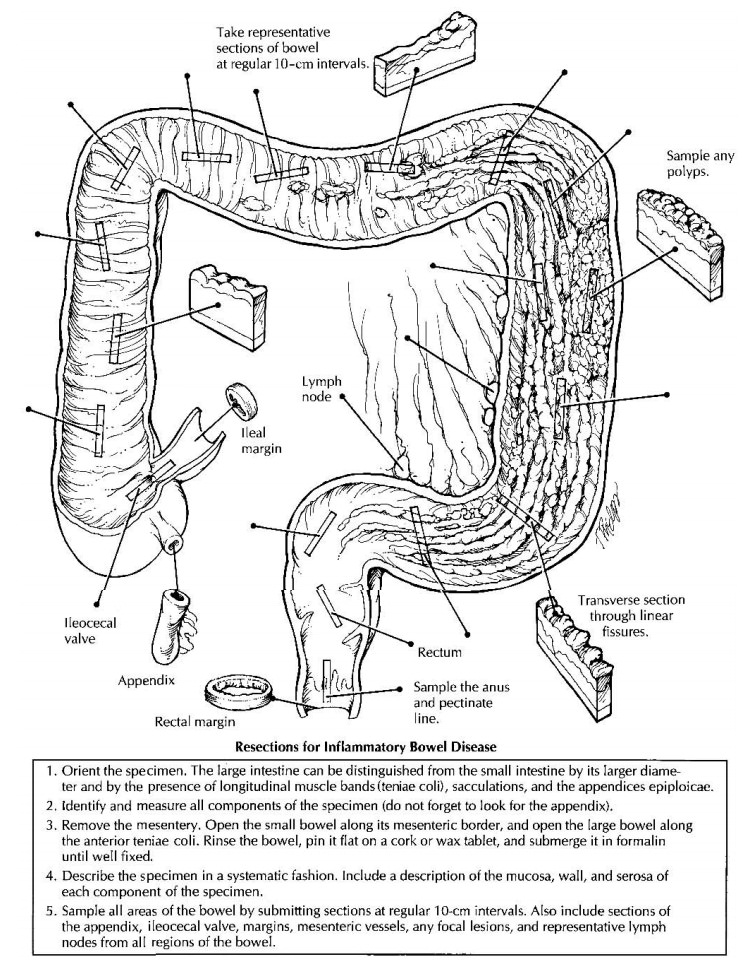

Resections of Small and Large Intestine for Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Given

the structural simplicity of the intestinal tract and the ease with which the

bowel can be opened, there is a strong tendency to rush into these dissections without

thinking ahead. The ap-proach to the non-neoplastic bowel specimen requires an

effective strategy that gives careful consideration to an organized gross

description, specimen photography and fixation, and details of dissection and

tissue sampling.

The Organized Gross Description

A good

gross description not only describes all the relevant gross findings but

presents these findings in an organized fashion. This can be a difficult task

in bowel resections, where the speci-men may consist of more than one structure

(e.g., ileum, appendix, cecum, and colon). Organize your gross description.

First, describe the speci-men after it has been examined and at least

par-tially dissected. This will make it possible to collect all of the gross

findings and integrate them into an organized statement. Second, always

de-scribe each component of the resection as an indi-vidual unit. For example,

describe the mucosa, wall, and serosa of the ileum and then move on to the

appendix, cecum, and finally the colon. Third, focus on the mucosa. Begin by

describ-ing the distribution of mucosal alterations (e.g., diffuse,

discontinuous) and then describe the specific characteristics of these changes

(e.g., ul-cerated, granular). Of course, no gross descrip-tion is complete without

a description of the wall, serosa, and mesentery; but for inflammatory bowel

disease, a less detailed description of these layers will generally suffice.

Specimen Dissection

Given

the structural simplicity of the bowel, opening these specimens is generally

straightfor-ward. When possible, the small intestine should be opened adjacent

to the mesentery. In contrast, the large intestine should be opened on the

anti-mesenteric border along the anterior (free) teniae coli. Remove the

mesentery before fixing the bowel. Treat the mesenteric soft tissues as though

For total colectomies, remove the mesentery as six separate portions,

and designate these as proximal ascending, distal ascending, proximal

transverse, distal transverse, proximal descending, and distal descending.

Although only representative lymph nodes need to be submitted, the six portions

should be clearly labeled and saved for easy retrieval if more ex-tensive lymph

node sampling is later required.

Specimen Fixation

In

general, the bowel should be fixed before it is photographed, described, and

sectioned. Subtle mucosal alterations (e.g., erosions, ulcerations, areas of

hemorrhage) that may not be apparent in the fresh specimen are often well

defined once the specimen is fixed. In most cases, the specimen can be opened

and pinned on a solid surface as a flat sheet and then submerged in formalin.

Some specimens may be so distorted that they cannot be easily opened and pinned

flat without the risk of cutting across structures (e.g., fistulae,

diverti-cula) and disrupting important relationships. These distorted specimens

may be best handled by infusing formalin into the lumen of the bowel and then

clamping both ends of the specimen. Whether the bowel is submerged or infused,

fecal material should first be rinsed from the muco-sal surface (a more

formidable challenge in the unopened specimen) using a gentle stream of an

isotonic solution.

Specimen Photography

Photographs of the specimen should be liberally taken to document further the gross findings, es-pecially the distribution and nature of the muco-sal alterations. Photograph the specimen after it has been opened and fixed. Photographs of the unopened bowel are generally useless. Fixation tends to both accentuate the mucosal alterations and reduce the amount of reflected light. Always position the specimen anatomically on the photography table. Total colectomies, for ex-ample, should be positioned so that the ascending colon is to the anatomic right, the descending colon is to the left, and the transverse colon is to the top and center. Finally, include close-up photographs to illustrate the details of the mucosal pathology.

Tissue Sampling

To

evaluate the distribution of inflammatory changes in the specimen, all areas of

the bowel should be sampled for histologic evaluation. One method that

consistently ensures adequate sam-pling is to submit representative sections at

10-cm intervals, beginning at the distal end of the specimen and proceeding

proximally in a step-wise fashion. This not only will ensure that the mucosa is

well sampled but will also provide information on the distribution of the

disease process. Of course, sections of any focal lesions such as ulcers or

polyps should be submitted in addition to these interval sections. Sections

should also be taken of the appendix and the ileocecal valve when these

structures are present. When no tumor is grossly apparent, the resection

margins may be taken as shave sections. In addi-tion to sampling the mesentery

for lymph nodes, submit sections of mesenteric blood vessels and of any focal

lesions such as fistula tracts or areas of fat necrosis. Indicate the site from

which all sections were taken on the Polaroid or digital photographs. Take

longitudinal sections (i.e., par-allel to the teniae coli). Exceptions are

permitted when, for example, a linear ulcer is best demon-strated by a

transverse section through the bowel.

Once

these principles regarding gross descrip-tion, fixation, dissection, and

sampling are mas-tered, the inflammatory bowel specimen can be handled with

relative ease. The initial step is to identify the structures that are present

in the re-sected specimen. The large intestine is readily distinguished from

the small intestine by its larger diameter and the presence of longitudinal

muscle bands (the teniae coli), sacculations (the haustra), and the appendices

epiploicae. In addi-tion, the small intestine shows mucosal folds that stretch

across the entire circumference of the bowel, whereas the mucosal folds of the

large in-testine are discontinuous. Several features may be helpful in

appreciating the various regions of the large intestine. The cecum is usually

quite apparent, and it can be used to identify the origin of the ascending

colon. The transverse colon can be recognized by its large mesenteric pedicle attachment,

while the sigmoid colon has a rela-tively short mesenteric pedicle. When a

portion of rectum is included in the specimen, it can be distinguished from the

sigmoid colon by the absence of a peritoneal surface lining.

The

initial description should be limited to a list of the structures present and

the dimensions of each. Further handling of the bowel is facili-tated by

removing the mesenteric fat. As de-scribed previously, these soft tissues

should be removed according to their anatomic location, and each portion should

be clearly labeled so it can be easily identified and retrieved. Most

pro-sectors have an easier time finding mesenteric lymph nodes while these

tissues are still in the fresh state. Remember, most of the lymph nodes are

found at the junction of the bowel and mesen-teric fat. Open the bowel along

its entire length, cutting the small bowel along its mesenteric at-tachment and

the large bowel along the anterior teniae. Gently rinse any fecal material from

the mucosal surface using a stream of isotonic solu-tion. Pin the opened bowel

flat on a solid surface, and submerge it in formalin.

Once the

specimen is fixed, complete the exam-ination of the mucosa, noting in the gross

descrip-tion the distribution and characteristics of the mucosal alterations.

Place the bowel in its correct anatomic position, and photograph it. Take a

Polaroid or digital photograph of the entire specimen, so that the sites from

which histologic sections were taken can be indicated on the image, and take

close-up views of focal lesions.

Remember

to section all regions of the bowel by using a method of stepwise sectioning at

regu-lar (i.e., 10-cm) intervals. Specific bowel sections should include the

proximal and distal resection margins, the ileocecal valve, the appendix, and

any focal lesions. If a neoplasm is not found, sam-pling of representative

lymph nodes from each level will suffice. Sampling of the mesentery should also

include a section of the mesenteric blood vessels and sections of any focal

lesions.

Important Issues to Address in Your Surgical Pathology Report on Non-Neoplastic Intestinal Disease

· What

procedure was performed, and what structures/organs are present?

· What

disease processes are present, and what is their location?

·

For inflammatory processes, are any

diver-ticula, strictures, fistulae, or perforations present?

·

Does the mucosa show any preneoplastic or

neoplastic changes?

·

Do the lymph nodes show any evidence of an

inflammatory process or metastatic disease? Record the number of lymph nodes examined

and the presence or absence of lymph node metastases.

·

What is the status of the mesenteric vessels?

Related Topics