Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : General Anesthetics

Mechanism of General Anesthetic Action

MECHANISM OF GENERAL ANESTHETIC

ACTION

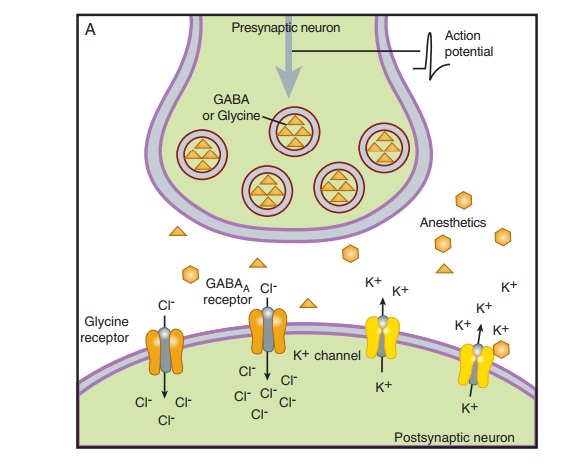

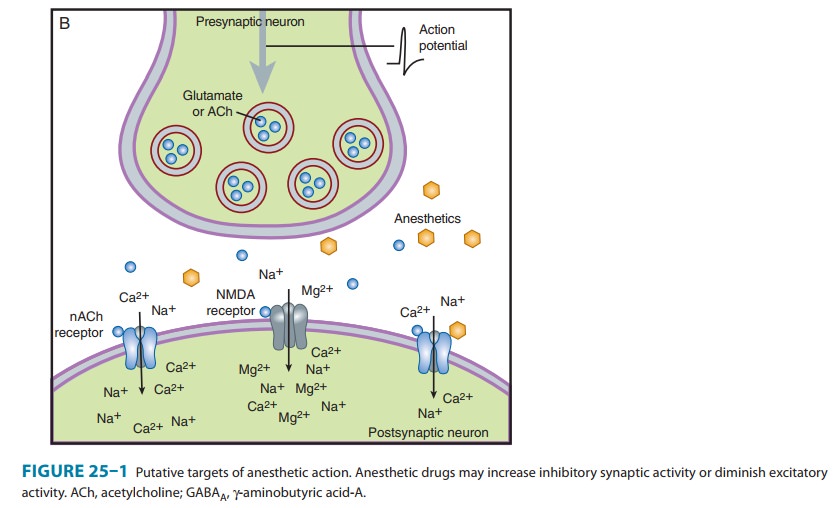

General anesthetics have been in clinical use for more than 160 years but their mechanism of action remains unknown. Initial research focused on identifying a single biologic site of action for these drugs. In recent years this “unitary theory” of anesthetic action has been supplanted by a more complex picture of molecular targets located at multiple levels of the central nervous system (CNS).Anesthetics affect neurons at various cellular locations, but the primary focus has been on the synapse. A presynaptic action may alter the release of neurotransmitters, whereas a postsynaptic effect may change the frequency or amplitude of impulses exiting the synapse. At the organ level, the effect of anesthetics may result from strengthening inhibition or from diminishing excitation within the CNS. Studies on isolated spinal cord tissue have demonstrated that excitatory transmission is impaired more strongly by anesthetics than inhibitory effects are potentiated.

Chloride

channels (γ-aminobutyric

acid-A [GABAA] and glycine receptors) and potassium channels (K2P,

possibly Kv, and KATP chan-nels) remain the primary inhibitory ion channels considered legiti-mate

candidates of anesthetic action. Excitatory

ion channel targets include those activated by acetylcholine (nicotinic and

muscarinic receptors), by excitatory amino acids

(amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazol-propionic acid [AMPA], kainate, and N-methyl-D-aspartate [NMDA] receptors),

or by serotonin (5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors). Figure 25–1

depicts the relation of these inhibitory and excitatory targets of anesthetics

within the context of the nerve terminal.

Sedation & Monitored Anesthesia Care

Many diagnostic and minor therapeutic surgical procedures can be performed without general anesthesia using sedation-based anesthetic techniques. In this setting, regional or local anesthesia supplemented with midazolam or propofol and opioid analgesics (or ketamine) may be a more appropriate and safer approach than general anesthesia for superficial surgical procedures. This anesthetic technique is known as monitored anesthesia care, often abbreviated as MAC, not to be confused with the minimal alveolar concentration for the comparison of potencies of inhaled anesthetics (see text and Box: What Does Anesthesia Represent & Where Does It Work?). The technique typically involves the use of intravenous midazolam for premedication (to provide anxiolysis, amnesia, and mild sedation) followed by a titrated, variable-rate propofol infusion (to provide moderate to deep levels of seda-tion). A potent opioid analgesic or ketamine may be added to minimize the discomfort associated with the injection of local anesthesia and the surgical manipulations.

Another approach, used primarily by nonanesthesiologists, is called conscious sedation. This technique refers to drug-induced alleviation of anxiety and pain in combination with an altered level of consciousness associated with the use of smaller doses of sedative medications. In this state the patient retains the ability to maintain a patent airway and is responsive to verbal commands. A wide variety of intravenous anesthetic drugs have proved to beuseful drugs in conscious sedation techniques (eg, diazepam, midazolam, propofol). Use of benzodiazepines and opioid anal-gesics (eg, fentanyl) in conscious sedation protocols has the advantage of being reversible by the specific receptor antagonist drugs (flumazenil and naloxone, respectively).A specialized form of sedation is occasionally required in the ICU, when patients are under severe stress and require mechanical ventilation for prolonged periods. In this situation, sedative-hypnotic drugs and low doses of intravenous anesthet-ics may be combined. Recently, dexmedetomidine has become a popular choice for this indication.Deep sedation is similar to a light state of general (intrave-nous) anesthesia involving decreased consciousness from which the patient is not easily aroused. The transition from deep seda-tion to general anesthesia is fluid, and it is sometimes difficult to clearly determine where the transition is. Because deep sedation is often accompanied by a loss of protective reflexes, an inability to maintain a patent airway, and lack of verbal responsiveness to surgical stimuli, this state may be indistinguishable from intrave-nous anesthesia. Intravenous agents used in deep sedation pro-tocols mainly include the sedative-hypnotics propofol and midazolam, sometimes in combination with potent opioid anal-gesics or ketamine, depending on the level of pain associated with the surgery or procedure.

Related Topics