Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : General Anesthetics

Benzodiazepines - Intravenous Anesthetics

BENZODIAZEPINES

Benzodiazepines

commonly used in the perioperative period include midazolam, lorazepam, and

less frequently, diazepam. Benzodiazepines are unique among the group of

intravenous anes-thetics in that their action can readily be terminated by

adminis-tration of their selective antagonist, flumazenil. Their most desired

effects are anxiolysis and anterograde amnesia, which are extremely useful for

premedication.

Pharmacokinetics in the Anesthesia Setting

The

highly lipid-soluble benzodiazepines rapidly enter the CNS, which accounts for

their rapid onset of action, followed by redis-tribution to inactive tissue

sites and subsequent termination of the drug effect.

Despite

its prompt passage into the brain, midazolam is con-sidered to have a slower

effect-site equilibration time than propo-fol and thiopental. In this regard,

intravenous doses of midazolam should be sufficiently spaced to permit the peak

clinical effect to be recognized before a repeat dose is considered. Midazolam

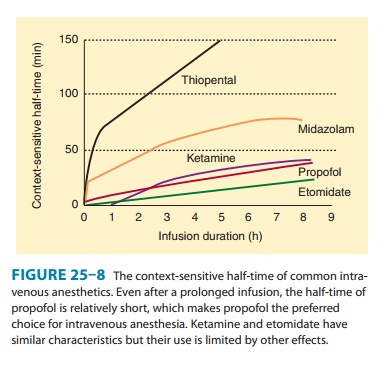

has the shortest context-sensitive half-time, which makes it the only one of

the three benzodiazepine drugs suitable for continuous infusion (Figure 25–8).

Organ System Effects

A. CNS Effects

Similar

to propofol and barbiturates, benzodiazepines decrease CMRO2 and

cerebral blood flow, but to a smaller extent. There appears to be a ceiling

effect for benzodiazepine-induced decreases in CMRO2 as evidenced by

midazolam’s inability to produce an isoelectric EEG. Patients with decreased

intracranial compliance demonstrate little or no change in ICP after the administration

of midazolam. Although neuroprotective properties have not been shown for

benzodiazepines, these drugs are potent anticonvulsants used in the treatment

of status epilepticus, alcohol withdrawal, and local anesthetic-induced

seizures. The CNS effects of benzodiazepines can be promptly terminated by

administration of the selective benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil, which

improves their safety profile.

B. Cardiovascular Effects

If

used for the induction of anesthesia, midazolam produces a greater decrease in

systemic blood pressure than comparable doses of diazepam. These changes are

most likely due to peripheral vaso-dilation inasmuch as cardiac output is not

changed. Similar to other intravenous induction agents, midazolam’s effect on

sys-temic blood pressure is exaggerated in hypovolemic patients.

C. Respiratory Effects

Benzodiazepines

produce minimal depression of ventilation, although transient apnea may follow

rapid intravenous administration of midazolam for induction of anesthesia,

especially in the presence of opioid premedication. Benzodiazepines decrease

the ventilatory response to carbon dioxide, but this effect is not usually

significant if they are administered alone. More severe respiratory depression

can occur when benzodiazepines are administered together with opioids. Another

problem affecting ventilation is airway obstruction induced by the hypnotic

effects of benzodiazepines.

D. Other Effects

Pain

during intravenous and intramuscular injection and subse-quent thrombophlebitis

are most pronounced with diazepam and reflect the poor water solubility of this

benzodiazepine, which requires an organic solvent in the formulation. Despite

its better solubility (which eliminates the need for an organic solvent),

midazolam may also produce pain on injection. Allergic reactions to benzodiazepines

are rare to nonexistent.

Clinical Uses & Dosage

Benzodiazepines

are most commonly used for preoperative medi-cation, intravenous sedation, and

suppression of seizure activity. Less frequently, midazolam and diazepam may

also be used to induce general anesthesia. The slow onset and prolonged

duration of action of lorazepam limit its usefulness for preoperative

medica-tion or induction of anesthesia, especially when rapid and sus-tained

awakening at the end of surgery is desirable. Although flumazenil (8–15 mcg/kg

IV) may be useful for treating patients experiencing delayed awakening, its

duration of action is brief (about 20 minutes) and resedation may occur.

The

amnestic, anxiolytic, and sedative effects of benzodiaz-epines make this class

of drugs the most popular choice for preop-erative medication. Midazolam (1–2

mg IV) is effective for premedication, sedation during regional anesthesia, and

brief therapeutic procedures. Midazolam has a more rapid onset, with greater

amnesia and less postoperative sedation, than diazepam. Midazolam is also the

most commonly used oral premedication for children; 0.5 mg/kg administered

orally 30 minutes before induction of anesthesia provides reliable sedation and

anxiolysis in children without producing delayed awakening.

The synergistic effects between benzodiazepines and other drugs, especially opioids and propofol, can be used to achieve bet-ter sedation and analgesia but may also greatly enhance their combined respiratory depression and may lead to airway obstruc-tion or apnea. Because benzodiazepine effects are more pro-nounced with increasing age, dose reduction and careful titration may be necessary in elderly patients.

General

anesthesia can be induced by the administration of midazolam (0.1–0.3 mg/kg

IV), but the onset of unconsciousness is slower than after the administration

of thiopental, propofol, or etomidate. Delayed awakening is a potential

disadvantage, limiting the usefulness of benzodiazepines for induction of

general anesthe-sia despite their advantage of less pronounced circulatory

effects.

Related Topics