Chapter: Biology of Disease: Diet and Disease

General Management of Nutritional Disorders

GENERAL MANAGEMENT OF NUTRITIONAL

DISORDERS

Patients who are malnourished or at risk of developing

malnutrition require appropriate therapy, which ranges from simple dietary advice

to long-term parenteral nutrition. The dietary needs of the patient must be

carefully assessed to provide the correct amounts of energy, protein, vitamins,

minerals and trace elements. Patients receive these diets by oral (Figure 10.39), tube and parenteral

feeding; the last is most commonly administered by intravenous infusion. Oral

supplementation should be used wherever possible and the common practice is to

encourage consumption of specific foods or supplements that rectify the

nutritional disorder in question. In cases where oral feeding is not possible,

then liquid food is administered through a nasal tube to the stomach or small

intestine. Tube feeding is particularly useful in patients with swallowing

difficulties or anorexia. During tube feeding, liquid may be pumped

continuously at a constant rate of 75 to 150 cm3 per hour for 8–24

h. Liquid foods for tube feeding are available commercially as formulae that

meet nearly all the patient needs. In some cases, food is administered as a

bolus, that is, infusing a discrete volume of formula through the tube under

gravity several times daily. It has the advantages of reducing the cost and

allowing stable long-term patients more mobility. Parenteral feeding bypasses

the GIT so nutrients are delivered directly into the blood. It is only used

when oral or tube feeding have been deemed unsuitable; such as in patients who

cannot eat or absorb food from the GIT. Total parenteral nutrition given via

the peripheral veins or, in cases of long-term nutrition, through a central

venous catheter can provide complete nutrition using preparations containing

appropriate amounts of energy, amino acids, vitamins, minerals and trace

elements. Like liquid foods for tube feeding, these preparations are available

commercially but they are occasionally prepared individually to meet a

patient’s specific needs. Patients on long-term total parenteral nutrition

require careful clinical and laboratory monitoring. Indeed, patients often have

an increased risk of infection at the venous catheter site so care is

necessary. Biochemical changes usually precede any clinical signs of nutrient

deficiency and so regular laboratory monitoring is essential for early

detection of any micronutrient deficiency.

Patients with PEM cannot immediately accept normal food because

there are digestive enzyme deficiencies and often gastroenteritis. Rehydration

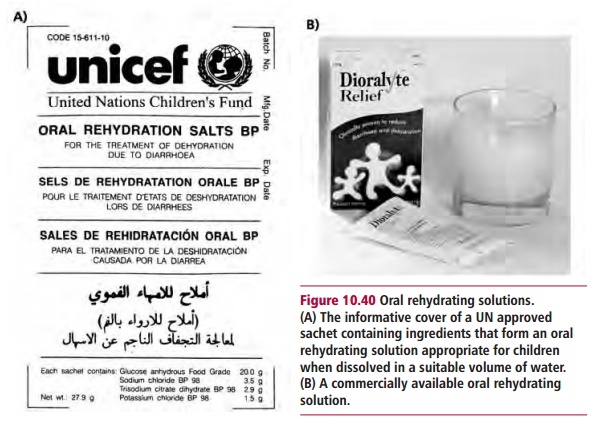

is a priority and oral solutions (Figure

10.40) achieve this in some cases, while intravenous infusions may be

necessary in severe cases. Diluted milk with added sugar may be given initially

and as this becomes accepted the proportion of milk can be gradually increased.

The cessation of diarrhea indicates that the health of the GIT mucosa is

improving and normal foods can be gradually returned to the diet.

The management of obesity aims to reduce food intake,

particularly total energy intake, and to encourage regular exercise. This is

often achieved by cutting down on high energy foods, such as fats and alcohol.

Education and psychological support can be helpful in cases of severe obesity.

Orlistat, an inhibitor of pancreatic lipase, has been used to manage obesity

since it reduces the digestion and absorption of dietary fats and sibutramine

to suppress the appetite, in conjunction with an energy-controlled diet, has

been used to control weight. Surgery is used in some cases of severe obesity.

Jejuno-ileal bypass surgery for morbid obesity was first performed in 1952. In

this process the end of the jejunum or the beginning of the ileum are removed

and the remaining portions joined together. Most of the small intestine is

removed leaving only a short length for digestion and absorption. Although

jejuno-ileal bypass surgery results in a very good weight loss, severe side

effects occur. The technique has been replaced with gastric bypass surgery

where the upper part of the stomach is connected to the small intestine about

one third of the way along its length. Thus only the lower part of the stomach

and approximately two thirds of the small intestine are available for digestion

and absorption, reducing energy intake and therefore weight, but dieting is

still likely to be required. Again, this operation is not without the risk of

developing serious postoperative complications. Liposuction may also be used to

remove fat from under the skin though this is typically performed mainly for

cosmetic rather than therapeutic reasons.

Eating disorders, such as AN and BN, are difficult to prevent

and remain hard to treat. There are seemingly few effective treatments and no

universally recognized plan of treatment. However, the goals of any therapy

must be to establish normal eating patterns and to restore the patient’s

nutritional status and weight. Usually a multidisciplinary approach tailored to

the individual is used. This will involve specialists in nutrition and mental

health in addition to clinicians. Therapy generally involves the family,

behavior modification and nutrition counseling, support groups and the use of

antidepressants. Most patients with AN or BN are treated as outpatients

although in severe cases hospitalization may be necessary. Given that

compliance is often problematic, AN and BN are generally considered to be

chronic disorders interrupted only by intermittent periods of short-lived

remission.

Related Topics