Chapter: Biology of Disease: Diet and Disease

Nutritional Disorders of Minerals and Trace Elements

NUTRITIONAL DISORDERS OF MINERALS AND TRACE ELEMENTS

Minerals and trace elements are necessary for numerous and

diverse metabolic activities. Clinical disorders arising from deficiencies in

the dietary intakes of minerals are not uncommon and a number are described.

Conditions caused by excessive mineral ingestion are less common but several

are also outlined.

The total quantity of any one trace element in the body is

usually less than 5 g and these elements are often required in quantities of

less than 20 mg per day, hence dietary deficiencies are uncommon. Chromium

deficiency can occur in patients on parenteral nutrition without adequate

supplementation and leads to glucose intolerance. An excess of chromium (II)

has no known symptoms, although chromium (III) and especially chromium (VI)

compounds are toxic. A deficiency of cobalt is rare and causes indigestion,

diarrhea, weight loss and a loss of memory. An excess of cobalt is not

associated with any known symptoms, although a high intake over a prolonged

period may lead to infertility in men. In addition, there are occasional

reports of cobalt cardiomyopathy following occupational exposure.

Copper deficiency is uncommon, except in patients on synthetic

oral or on long-term parenteral nutrition. It can occur in infants because of

malnutrition, malabsorption, chronic diarrhea or prolonged feeding with low

copper milk diets. Premature infants are particularly susceptible because of

their low copper stores in the liver. Copper deficiency causes neutropenia and

hypochromic anemia in the early stages, both of which respond to dietary copper

but not iron. This is followed by bone abnormalities such as osteoporosis,

decreased pigmentation of the skin, pallor and neurological abnormalities in

the later stages. A dietary excess of copper is rare but occasionally happens

following food contamination and causes salivation, stomach pain, nausea,

vomiting and diarrhea.

Nearly half of dietary fluoride is taken up by bone and can

influence its mechanical properties. The incorporation of fluoride in tooth

enamel as fluorapatite makes teeth more resistant to dental caries as it

resists breakdown by acids. Fluoride deficiency leads to impaired bone

formation and dental defects.

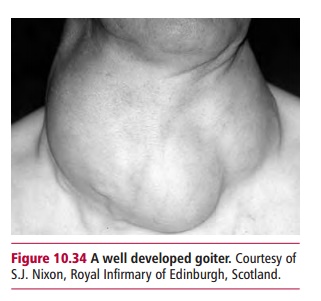

Iodine deficiency causes an enlargement of the thyroid gland

called goiter (Figure 10.34), while a

prolonged deficiency in children can lead to cretinism . Iodine deficiency is

commonest in upland areas with thin limestone soil because minerals, such as

iodine are easily leached from these types of soils and plants in the area are

iodine deficient. The situation is exacerbated if commercial iodized salt is

not available. In some areas of Africa, Brazil and the Himalayas, more than 90%

of the population may develop goiter due to iodine deficiency. Excessive intake

of dietary iodide can also lead to goiter. This is most commonly seen in

Japanese communities who have a high dietary intake of seaweed.

A lack of iron leads to anemia, which is described. Increased intake of dietary, medicinal or transfused iron can cause hemosiderosis, characterized by deposits of iron compounds in organs such as

the liver and heart. Acute ingestion of large doses of ferrous salts can be

fatal, particularly in children under the age of two. Manganese deficiency is

rare but is believed to cause ataxia, hearing loss and dizziness. Inhalation of

dust from mining and other industrial sources can lead to manganese toxicity

and causes severe neurological dysfunction, similar to Parkinson’s disease . A

dietary deficiency of molybdenum has not been reported. However, molybdenum

deficiency was noted in a patient on parenteral nutrition who suffered from mental

disturbances that progressed to coma. Supplementation of molybdenum improved

the patient’s clinical condition. Levels of manganese in food and water must

exceed 100 mg kg–1 body weight to produce manganese toxicity.

However, few data are available but the major signs include diarrhea and

anemia. The high concentrations are thought to stimulate xanthine oxidase,

leading to increased serum uric acid and gout .

Selenium deficiency results from a low dietary intake in parts

of the world with soils of low selenium content and has been reported in

patients on long-term parenteral nutrition. A deficiency of selenium may lead

to a cardiomyopathy. In China, this is called Keshan’s disease and affects

young women and children in selenium deficient regions and although selenium

deficiency is a basic factor in Keshan’s disease, its occurrence is seasonal

and it is associated with viral infections that cause inflammation of the

heart. Prophylactic selenium prevents the disease developing but selenium

supplements do not reverse heart muscle damage. A large intake of selenium

causes selenosis, a condition characterized by loss of hair, skin and nails.

Zinc deficiency is relatively common in populations in rural

areas of the Middle East and subtropical and tropical areas where unleavened

whole wheat bread can provide up to 75% of the energy intake. The little zinc

in wheat is bound by the relatively large amounts of phytic acid and fiber

present that inhibit its absorption. This is not a problem in leavened bread,

as yeasts produce phytases that inactivate the phytic acid. Zinc deficiency

also occurs during prolonged parenteral nutrition if inadequate amounts are

provided. A deficiency is associated with a period of severe catabolism, as

would occur in PEM. A severe deficiency occurs in the skin condition

acrodermatitis enteropathica, where there is an inherited defect in GIT zinc

absorption. A deficiency of zinc delays the onset of puberty. High doses of

zinc reduce the amount of copper the body can absorb causing anemia and

weakness of the bones.

Related Topics