Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Perioperative & Critical Care Medicine: Critical Care

Discontinuing Mechanical Ventilation

Discontinuing

Mechanical Ventilation

There are two phases to discontinuing mechanical ventilation. In the

first, “readiness testing,” so-called weaning parameters and other subjective

and objec-tive assessments are used to determine whether the patient can

sustain progressive withdrawal of mechanical ventilator support. The second

phase, “weaning” or “liberation,” describes the way in which mechanical support

is removed.

Readiness testing should include determining

whether the process that necessitated mechanical ventilation has been reversed

or controlled. Com-plicating factors such as bronchospasm, heart fail-ure, infection,

malnutrition, metabolic acidosis or alkalosis, anemia, increased CO 2 production due to increased carbohydrate

loads, altered mental status, and sleep deprivation should be adequately

treated. Underlying lung disease and respiratory muscle wasting from prolonged

disuse often complicate weaning. Patients who fail to wean despite apparent

readiness often have COPD or chronic heart failure.

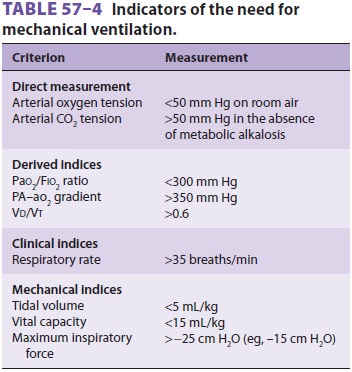

Weaning (or liberation) from mechanical

venti-lation should be considered when patients no longer meet general criteria

for mechanical ventilation (see Table 57–4). In general, this occurs when

patients have a pH greater than 7.25, show adequate arte-rial oxygen saturation

while receiving FIO2 less than 0.5, are able to spontaneously breathe, are hemo-dynamically

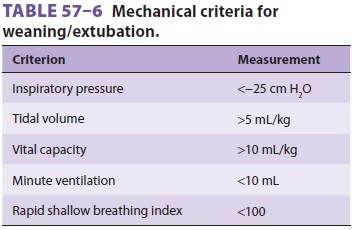

stable, and have no current signs of myocardial ischemia. Additional mechanical

indi-ces have also been suggested (Table 57–6).

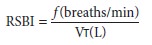

Useful weaning parameters include arterial blood gas ten-sions, respiratory

rate, and rapid shallow breathing index (RSBI, see). Intact airway reflexes and

a cooperative patient are also mandatory prior to completion of the weaning and

extubation unless the patient will retain a cuffed tracheostomy tube.

Similarly, adequate oxygenation (arterial oxygen saturation >90% on 40–50% O2 with <5 cm H2O of PEEP) is imperative prior to extubation. When the patient is weaned

from mechanical ventilation and extubation is planned, the RSBI is frequently

used to help predict who can be successfully weaned from mechanical ventilation

and extubated. With the patient breathing spontaneously on a Τ-piece, the VT (in liters) and respiratory

rate (f) are measured:

Patients with an RSBI less than 100 can be success-fully extubated.

Those with an RSBI greater than 120 should retain some degree of mechanical

ventilator support.

The common techniques to wean a patient from the ventilator include

SIMV, pressure sup-port, or periods of spontaneous breathing alone on a Τ-piece or on low levels of CPAP.

Mandatory minute ventilation has also been suggested as an ideal weaning

technique, but experience with it is limited. Finally, many institutions use

“automated tube compensation” to provide just enough pres-sure support to compensate

for the resistance of breathing through an endotracheal tube. Newer mechanical

ventilators have a setting that will auto-matically adjust gas flows to make

this adjustment. In practice in adults breathing through conven-tionally sized

tubes (7.5–8.5), the adjustment will typically amount to pressure support of 5

cm H2O and PEEP of 5 cm H2O.

Weaning with SIMV

With SIMV the number of mechanical breaths is progressively decreased

(by 1–2 breaths/min) as long as the arterial CO2 tension and respiratory rate

remain acceptable (generally <45–50 mm

Hg and <30 breaths/min, respectively).

If pressure sup-port is concomitantly used, it should generally be reduced to

5–8 cm H 2O. In patients with acid–base disturbances or chronic CO2

retention, arterial blood pH (>7.35) is

more useful than CO 2 tension. Blood gas

measurements can be checked after a minimum of 15–30 min at each setting. When

an IMV of 2–4 breaths is reached, mechanical ventila-tion is discontinued if

arterial oxygenation remains acceptable.

Weaning with PSV

Weaning with PSV alone is accomplished by

gradu-ally decreasing the pressure support level by 2–3 cm H2O while VT, arterial blood gas tensions, and

respi-ratory rate are monitored (using the same criteria as for IMV). The goal

is to try to ensure a VT of 4–6 mL/ kg and an f of less than 30 with acceptable PaO2 and PaCO2. When a pressure support level of 5–8 cm H2O is reached, the patient is considered weaned.

Weaning with a T-Piece or CPAP

Τ-piece trials allow observation while the

patient breathes spontaneously without any mechanical breaths. The Τ-piece

attaches directly to the tracheal tube or tracheostomy tube and has corrugated

tub-ing on the other two limbs. A humidified oxygen–air mixture flows into the

proximal limb and exits from the distal limb. Sufficient gas flow must be given

in the proximal limb to prevent the mist from being completely drawn back at

the distal limb during inspiration; this ensures that the patient is receiving

the desired oxygen concentration. The patient is observed closely during this

period; obvious new signs of fatigue, chest retractions, tachypnea,

tachy-cardia, arrhythmias, or hypertension or hypotension should terminate the

trial. If the patient appears to tolerate the trial period and the RSBI is less

than 100, mechanical ventilation can be discontinued perma-nently. If the

patient can also protect and clear the airway, the tracheal tube can be

removed.

If the patient has been intubated for a

pro-longed period or has severe underlying lung disease, sequential Τ-piece trials may be necessary. Periodic

trials of 10–30 min are initiated and progressively increased by 5–10 min or

longer per trial as long as the patient appears comfortable and maintains

acceptable arterial blood gas measurements.

Many patients develop progressive atelectasis during prolonged Τ-piece trials. This may reflect the

absence of a normal “physiological” PEEP when the larynx is bypassed by a

tracheal tube. If this is a concern, spontaneous breathing trials on low levels

(5 cm H2O) of CPAP can be tried. The CPAP helps maintain FRC and prevent

atelectasis.

Related Topics