Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Chest and Lower Respiratory Tract Disorders

Atelectasis

Atelectasis

Atelectasis refers to closure or

collapse of alveoli and often is described in relation to x-ray findings and

clinical signs and symptoms. Atelectasis may be acute or chronic and may cover

a broad range of pathophysiologic changes, from microatelectasis (which is not

detectable on chest x-ray) to macroatelectasis with loss of segmental, lobar,

or overall lung volume. The most commonly described atelectasis is acute

atelectasis, which occurs frequently in the postoperative setting or in people

who are immobilized and have a shallow, monotonous breathing pattern. Excess

secretions or mucus plugs may also cause obstruction of airflow and result in

atelectasis in an area of the lung. Atelectasis also is observed in patients

with a chronic airway obstruction that impedes or blocks air flow to an area of

the lung (eg, obstructive atelectasis in the patient with lung cancer that is

invading or compressing the airways).This type of atelectasis is more insidious

and slower in onset.

Pathophysiology

Atelectasis may occur in the adult as a

result of reduced alveolar ventilation or any type of blockage that impedes the

passage of air to and from the alveoli that normally receive air through the

bronchi and network of airways. The trapped alveolar air becomes absorbed into

the bloodstream, but outside air cannot replace the absorbed air because of the

blockage. As a result, the isolated portion of the lung becomes airless and the

alveoli collapse. This may occur with altered breathing patterns, retained

secretions, pain, alterations in small airway function, prolongedsupine

positioning, increased abdominal pressure, reduced lung volumes due to

musculoskeletal or neurologic disorders, restrictive defects, and specific

surgical procedures (eg, upper abdomi nal, thoracic, or open heart surgery).

Persistent low lung volumessecretions or a mass obstructing or impeding

airflow, and compression of lung tissue may all cause collapse or obstruction

of the airways, which leads to atelectasis.

The postoperative patient is at high

risk for atelectasis because of the numerous respiratory changes that may

occur. A monotonous low tidal breathing pattern may cause airway closure and

alveolar collapse. This results from the effects of anesthesia or analgesic

agents, supine positioning, splinting of the chest wall because of pain, and

abdominal distention. The postoperative patient may also have secretion

retention, airway obstruction, and an impaired cough reflex or may be reluctant

to cough because of pain. Figure 23-1 shows the pathogenic mechanisms and

consequences of acute atelectasis in the postoperative patient.

Atelectasis resulting from bronchial obstruction by secretions may occur in patients with impaired cough mechanisms (eg,postoperative, musculoskeletal or neurologic disorders) or in debilitated, bedridden patients. Atelectasis may also result from excessive pressure on the lung tissue, which restricts normal lung expansion on inspiration. Such pressure may be produced by fluid accumulating within the pleural space (pleural effusion), air in the pleural space (pneumothorax), or blood in the pleural space (hemothorax). The pleural space is the area between the parietal and the visceral pleurae. Pressure may also be produced by a pericardium distended with fluid (pericardial effusion), tumor growth within the thorax, or an elevated diaphragm.

Clinical Manifestations

The

development of atelectasis usually is insidious. Signs and symptoms include

cough, sputum production, and low-grade fever. Fever is universally cited as a

clinical sign of atelectasis, but there are few data to support this. Most

likely the fever that ac-companies atelectasis is due to infection or

inflammation distal to the obstructed airway.

In

acute atelectasis involving a large amount of lung tissue (lobar atelectasis),

marked respiratory distress may be observed. In addition to the above signs and

symptoms, dyspnea, tachycardia, tachypnea, pleural pain, and central cyanosis (a bluish skin hue

that is a late sign of hypoxemia) may be anticipated. The pa-tient

characteristically has difficulty breathing in the supine posi-tion and is

anxious. Signs and symptoms of chronic atelectasis are similar to those of

acute atelectasis. Because the alveolar collapse is chronic, infection may

occur distal to the obstruction. Thus, the signs and symptoms of a pulmonary

infection also may be present.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Decreased

breath sounds and crackles are heard over the affected area. In addition, chest

x-ray findings may reveal patchy infiltrates or consolidated areas. In the

patient who is confined to bed,atelectasis is usually diagnosed by chest x-ray

or identified by physical assessment in the dependent, posterior, basilar areas

of the lungs. Depending on the degree of hypoxemia, pulse oxime-try (SpO2)

may demonstrate a low saturation of hemoglobin with oxygen (less than 90%) or a

lower-than-normal partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2).

Prevention

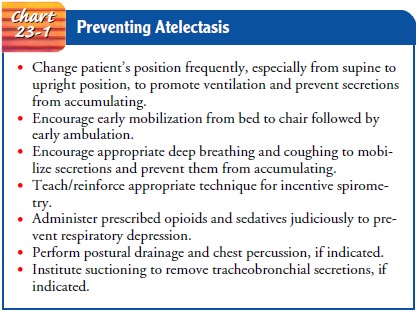

Nursing

measures to prevent atelectasis include frequent turning, early mobilization,

and strategies to expand the lungs and to man-age secretions. Deep-breathing

maneuvers (at least every 2 hours) assist in preventing and treating

atelectasis. The performance of these maneuvers requires a patient who is alert

and cooperative. Patient education and reinforcement are key to the success of

these interventions. The use of incentive spirometry or voluntary deep

breathing enhances lung expansion, decreases the potential for airway closure,

and may generate a cough. Secretion management techniques may include directed

cough, suctioning, aerosol neb-ulizer treatments followed by chest physical

therapy (postural drainage and chest percussion), or bronchoscopy. In some

set-tings, a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) is used to dispense a bron-chodilator rather

than an aerosol nebulizer treatment. Chart 23-1 summarizes measures to prevent

atelectasis.

Management

The

goal in treating the patient with atelectasis is to improve ven-tilation and

remove secretions. The strategies to prevent atelec-tasis, which include

frequent turning, early ambulation, lung volume expansion maneuvers (eg,

deep-breathing exercises, in-centive spirometry), and coughing also serve as

the first-line mea-sures to minimize or treat atelectasis by improving

ventilation. In patients who do not respond to first-line measures or who

cannot perform deep-breathing exercises, other treatments such as posi-tive

expiratory pressure or PEP therapy (a simple mask and one-way valve system that

provides varying amounts of expiratory resistance [usually 5 to 15 cm H2O]),

continuous or intermittent positive pressure-breathing (IPPB), or bronchoscopy

may be used. Although IPPB may be used in some settings, few data sup-port its

use in the postoperative setting (Duffy & Farley, 1993). Before initiating

more complex, costly, and labor-intensive ther-apies, the nurse should ask

several questions:

· Has the patient been given an adequate trial of deep-breathing exercises?

·

Has the patient received adequate

education, supervision, and coaching to carry out the deep-breathing exercises?

·

Have other factors been evaluated

that may impair ventila-tion or prohibit a good patient effort (eg, lack of

turning, mobilization; excessive pain; excessive sedation)?

If

the cause of atelectasis is bronchial obstruction from secre-tions, the

secretions must be removed by coughing or suctioning to permit air to re-enter

that portion of the lung. Chest physical ther-apy (chest percussion and

postural drainage) may also be used to mobilize secretions. Nebulizer

treatments with a bronchodilator medication or sodium bicarbonate may be used

to assist the patient in the expectoration of secretions. If respiratory care

measures fail to remove the obstruction, a bronchoscopy is performed. Severe or

massive atelectasis may lead to acute respiratory failure, especially in a

patient with underlying lung disease. Endotracheal intubation and mechanical

ventilation may be necessary. Prompt treatment re-duces the risk for acute

respiratory failure or pneumonia.

If

atelectasis has resulted from compression of lung tissue, the goal is to

decrease the compression. With a large pleural effusion that is compressing

lung tissue and causing alveolar collapse, treatment may include thoracentesis, removal of the fluid by

needle aspiration, or insertion of a chest tube. The measures to increase lung

expansion described above also are used.

Management

of chronic atelectasis focuses on removing the cause of the obstruction of the

airways or the compression of the lung tissue. For example, bronchoscopy may be

used to open an airway obstructed by lung cancer or a nonmalignant lesion, and

the procedure may involve cryotherapy or laser therapy. The goal is to reopen

the airways and provide ventilation to the collapsed area. In some cases,

surgical management may be indicated.

Related Topics