Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Chest and Lower Respiratory Tract Disorders

Blunt Trauma

BLUNT TRAUMA

Although

blunt chest trauma is more common, it is often diffi-cult to identify the

extent of the damage because the symptoms may be generalized and vague. In

addition, patients may not seek immediate medical attention, which may

complicate the problem.

Pathophysiology

Injuries

to the chest are often life-threatening and result in one or more of the

following pathologic mechanisms:

·

Hypoxemia from disruption of the

airway; injury to the lung parenchyma, rib cage, and respiratory musculature;

massive hemorrhage; collapsed lung; and pneumothorax

·

Hypovolemia from massive fluid loss

from the great vessels, cardiac rupture, or hemothorax

·

Cardiac failure from cardiac

tamponade, cardiac contusion, or increased intrathoracic pressure

These

mechanisms frequently result in impaired ventilation and perfusion leading to

ARF, hypovolemic shock, and death.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Time

is critical in treating chest trauma. Therefore, it is essential to assess the

patient immediately to determine the following:

·

When the injury occurred

·

Mechanism of injury

·

Level of responsiveness

·

Specific injuries

·

Estimated blood loss

·

Recent drug or alcohol use

·

Prehospital treatment

The

initial assessment of thoracic injuries includes assessment of the patient for

airway obstruction, tension pneumothorax, open pneumothorax, massive

hemothorax, flail chest, and cardiac tamponade. These injuries are

life-threatening and need imme-diate treatment. Secondary assessment would

include simple pneumothorax, hemothorax, pulmonary contusion, traumatic aortic

rupture, tracheobronchial disruption, esophageal perfora-tion, traumatic

diaphragmatic injury, and penetrating wounds to the mediastinum (Owens,

Chaudry, Eggerstedt & Smith, 2000). Although listed as secondary, these

injuries may be life-threatening as well depending upon the circumstances.

The

physical examination includes inspection of the airway, thorax, neck veins, and

breathing difficulty. Specifics include as-sessing the rate and depth of

breathing for abnormalities, such as stridor, cyanosis, nasal flaring, use of

accessory muscles, drooling, and overt trauma to the face, mouth, or neck. The

chest should be assessed for symmetric movement, symmetry of breath sounds,

open chest wounds, entrance or exit wounds, impaled objects, tracheal shift,

distended neck veins, subcutaneous emphysema, and paradoxical chest wall

motion. In addition, the chest wall should be assessed for bruising, petechiae,

lacerations, and burns. The vital signs and skin color are assessed for signs

of shock. The thorax is palpated for tenderness and crepitus; the position of

the trachea is also assessed.

The

initial diagnostic workup includes a chest x-ray, CT scan, complete blood

count, clotting studies, type and cross-match, electrolytes, oxygen saturation,

arterial blood gas analysis, and ECG. The patient is completely undressed to

avoid missing ad-ditional injuries that can complicate care. Many patients with

in-juries involving the chest have associated head and abdominal injuries that

require attention. Ongoing assessment is essential to monitor the patient’s

response to treatment and to detect early signs of clinical deterioration.

Medical Management

The

goals of treatment are to evaluate the patient’s condition and to initiate

aggressive resuscitation. An airway is immediately es-tablished with oxygen

support and, in some cases, intubation and ventilatory support. Re-establishing

fluid volume and negative in-trapleural pressure and draining intrapleural

fluid and blood are essential.

The

potential for massive blood loss and exsanguination with blunt or penetrating

chest injuries is high because of injury to the great blood vessels. Many

patients die at the scene or are in shock by the time help arrives. Agitation

and irrational and combative behavior are signs of decreased oxygen delivery to

the cerebral cortex. Strategies to restore and maintain cardiopulmonary

func-tion include ensuring an adequate airway and ventilation, stabi-lizing and

re-establishing chest wall integrity, occluding any opening into the chest

(open pneumothorax), and draining or re-moving any air or fluid from the thorax

to relieve pneumothorax, hemothorax, or cardiac tamponade. Hypovolemia and low

car-diac output must be corrected. Many of these treatment efforts, along with

the control of hemorrhage, are usually carried out si-multaneously at the scene

of the injury or in the emergency de-partment. Depending on the success of

efforts to control the hemorrhage in the emergency department, the patient may

be taken immediately to the operating room. Principles of manage-ment are

essentially those pertaining to care of the postoperative thoracic patient.

Sternal and Rib Fractures

Sternal

fractures are most common in motor vehicle crashes with a direct blow to the

sternum via the steering wheel and are most common in women, patients over age

50, and those using shoul-der restraints (Owens, Chaudry, Eggerstedt &

Smith, 2000).

Rib

fractures are the most common type of chest trauma, oc-curring in more than 60%

of patients admitted with blunt chest injury. Most rib fractures are benign and

are treated conserva-tively. Fractures of the first three ribs are rare but can

result in a high mortality rate because they are associated with laceration of

the subclavian artery or vein. The fifth through ninth ribs are the most common

sites of fractures. Fractures of the lower ribs are as-sociated with injury to

the spleen and liver, which may be lacer-ated by fragmented sections of the

rib.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The

patient with sternal fractures has anterior chest pain, over-lying tenderness,

ecchymosis, crepitus, swelling, and the poten-tial of a chest wall deformity.

For the patient with rib fractures, clinical manifestations are similar: severe

pain, point tenderness,and muscle spasm over the area of the fracture, which is

aggra-vated by coughing, deep breathing, and movement. The area around the

fracture may be bruised. To reduce the pain, the patient splints the chest by

breathing in a shallow manner and avoids sighs, deep breaths, coughing, and

movement. This reluctance to move or breathe deeply results in diminished

ventilation, collapse of unaerated alveoli (atelectasis), pneumonitis, and

hypoxemia. Respiratory insufficiency and failure can be the outcomes of such a

cycle.

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS

The

patient with a sternal fracture must be closely evaluated for underlying

cardiac injuries. A crackling, grating sound in the tho-rax (subcutaneous

crepitus) may be detected with auscultation. The diagnostic workup may include

a chest x-ray, rib films of a specific area, ECG, continuous pulse oximetry,

and arterial blood gas analysis.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Medical

management of the patient with a sternal fracture is di-rected toward

controlling pain, avoiding excessive activity, and treating any associated

injuries. Surgical fixation is rarely neces-sary unless fragments are grossly

displaced and pose a potential for further injury.

The

goals of treatment for rib fractures are to control pain and to detect and

treat the injury. Sedation is used to relieve pain and to allow deep breathing

and coughing. Care must be taken to avoid oversedation and suppression of the

respiratory drive. Alter-native strategies to relieve pain include an

intercostal nerve block and ice over the fracture site; a chest binder may

decrease pain on movement. Usually the pain abates in 5 to 7 days, and

discom-fort can be controlled with epidural analgesia, patient-controlled

analgesia, or nonopioid analgesia. Most rib fractures heal in 3 to 6 weeks. The

patient is monitored closely for signs and symptoms of associated injuries.

Flail Chest

Flail

chest is frequently a complication of blunt chest trauma from a steering wheel

injury. It usually occurs when three or more adjacent ribs (multiple contiguous

ribs) are fractured at two or more sites, resulting in free-floating rib

segments. It may also result as a combination fracture of ribs and costal

cartilages or ster-num (Owens, Chaudry, Eggerstedt & Smith, 2000). As a

result, the chest wall loses stability and there is subsequent respiratory

impairment and usually severe respiratory distress.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

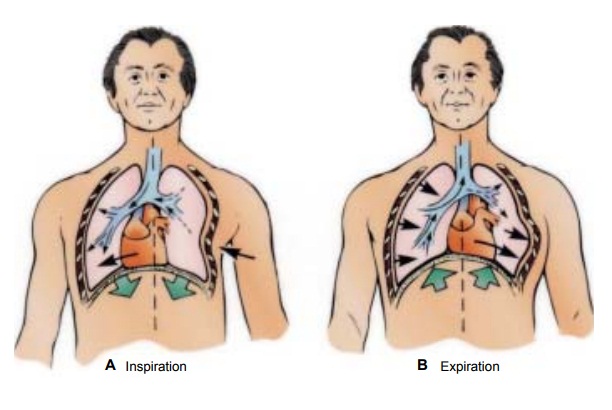

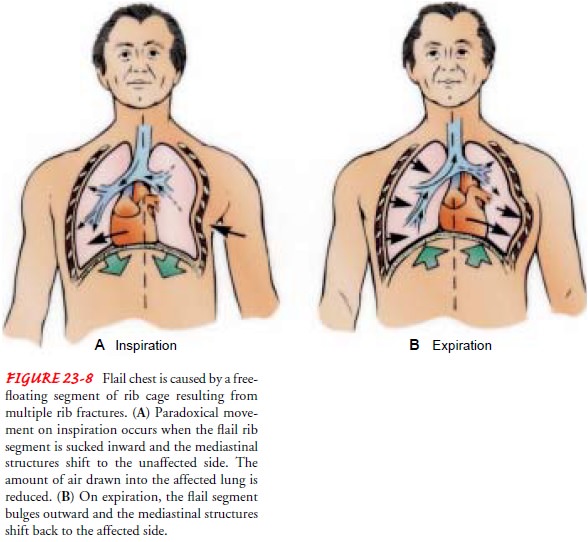

During

inspiration, as the chest expands, the detached part of the rib segment (flail

segment) moves in a paradoxical manner (pen-delluft movement) in that it is

pulled inward during inspiration, reducing the amount of air that can be drawn

into the lungs. On expiration, because the intrathoracic pressure exceeds

atmospheric pressure, the flail segment bulges outward, impairing the patient’s

ability to exhale. The mediastinum then shifts back to the affected side (Fig.

23-8). This paradoxical action results in increased dead space, a reduction in

alveolar ventilation, and decreased compli-ance. Retained airway secretions and

atelectasis frequently ac-company flail chest. The patient has hypoxemia, and

if gas exchange is greatly compromised, respiratory acidosis develops as a

result of CO2 retention. Hypotension, inadequate

tissue perfu-sion, and metabolic acidosis often follow as the paradoxical

mo-tion of the mediastinum decreases cardiac output.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

As

with rib fracture, treatment of flail chest is usually supportive. Management

includes providing ventilatory support, clearing se-cretions from the lungs,

and controlling pain. The specific man-agement depends on the degree of

respiratory dysfunction. If only a small segment of the chest is involved, the

objectives are to clear the airway through positioning, coughing, deep

breathing, and suctioning to aid in the expansion of the lung, and to relieve

pain by intercostal nerve blocks, high thoracic epidural blocks, or cau-tious

use of intravenous opioids.

For

mild to moderate flail chest injuries, the underlying pul-monary contusion is

treated by monitoring fluid intake and ap-propriate fluid replacement, while at

the same time relieving chest pain. Pulmonary physiotherapy focusing on lung

volume expan-sion and secretion management techniques are performed. The

patient is closely monitored for further respiratory compromise.

When a severe flail chest injury is encountered, endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation are required to provide in-ternal pneumatic stabilization of the flail chest and to correct ab-normalities in gas exchange.

This helps to treat the underlying pulmonary

contusion, serves to stabilize the thoracic cage to allow the fractures to

heal, and improves alveolar ventilation and in-trathoracic volume by decreasing

the work of breathing. This treatment modality requires endotracheal intubation

and venti-lator support. Differing modes of ventilation are used depending on

the patient’s underlying disease and specific needs.

In

rare circumstances, surgery may be required to more quickly stabilize the flail

segment. This may be used in the patient who is difficult to ventilate or the

high-risk patient with under-lying lung disease who may be difficult to wean

from mechanical ventilation.

Regardless

of the type of treatment, the patient is carefully monitored by serial chest

x-rays, arterial blood gas analysis, pulse oximetry, and bedside pulmonary

function monitoring. Pain management is key to successful treatment.

Patient-controlled analgesia, intercostal nerve blocks, epidural analgesia, and

intra-pleural administration of opioids may be used to control tho-racic pain.

Pulmonary Contusion

Pulmonary

contusion is observed in about 20% of adult patients with multiple traumatic

injuries and in a higher percentage of children due to increased compliance of

the chest wall. It is de-fined as damage to the lung tissues resulting in

hemorrhage and localized edema. It is associated with chest trauma when there

is rapid compression and decompression to the chest wall (ie, blunt trauma). It

may not be evident initially on examination but will develop in the

posttraumatic period.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The

primary pathologic defect is an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the

interstitial and intra-alveolar spaces. It is thought that injury to the lung

parenchyma and its capillary network results in a leakage of serum protein and

plasma. The leaking serum protein exerts an osmotic pressure that enhances loss

of fluid from the cap-illaries. Blood, edema, and cellular debris (from

cellular response to injury) enter the lung and accumulate in the bronchioles

and alveolar surface, where they interfere with gas exchange. An in-crease in

pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary artery pressure occurs. The patient

has hypoxemia and carbon dioxide retention. Occasionally, a contused lung

occurs on the other side of the point of body impact; this is called a

contrecoup contusion.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Pulmonary

contusion may be mild, moderate, or severe. The clinical manifestations vary

from tachypnea, tachycardia, pleu-ritic chest pain, hypoxemia, and blood-tinged

secretions to more severe tachypnea, tachycardia, crackles, frank bleeding,

severe hy-poxemia, and respiratory acidosis. Changes in sensorium, in-cluding increased

agitation or combative irrational behavior, may be signs of hypoxemia.

In

addition, the patient with moderate pulmonary contusion has a large amount of

mucus, serum, and frank blood in the tra-cheobronchial tree; the patient often

has a constant cough but cannot clear the secretions. A patient with severe

pulmonary con-tusion has the signs and symptoms of ARDS; these may include

central cyanosis, agitation, combativeness, and productive cough with frothy,

bloody secretions.

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS

The

efficiency of gas exchange is determined by pulse oximetry and arterial blood

gas measurements. Pulse oximetry is also used to measure oxygen saturation

continuously. The chest x-ray may show pulmonary infiltration. The initial

chest x-ray may show no changes; in fact, changes may not appear for 1 or 2

days after the injury.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Treatment

priorities include maintaining the airway, providing adequate oxygenation, and

controlling pain. In mild pulmonary contusion, adequate hydration via

intravenous fluids and oral in-take is important to mobilize secretions.

However, fluid intake must be closely monitored to avoid hypervolemia. Volume

ex-pansion techniques, postural drainage, physiotherapy including coughing, and

endotracheal suctioning are used to remove the se-cretions. Pain is managed by

intercostal nerve blocks or by opi-oids via patient-controlled analgesia or

other methods. Usually, antimicrobial therapy is administered because the

damaged lung is susceptible to infection. Supplemental oxygen is usually given

by mask or cannula for 24 to 36 hours.

The

patient with moderate pulmonary contusion may require bronchoscopy to remove

secretions; intubation and mechanical ventilation with PEEP may also be

necessary to maintain the pressure and keep the lungs inflated. Diuretics may

be given to reduce edema. A nasogastric tube is inserted to relieve

gastro-intestinal distention.

The

patient with severe contusion may develop respiratory failure and may require

aggressive treatment with endotracheal intubation and ventilatory support,

diuretics, and fluid restric-tion. Colloids and crystalloid solutions may be

used to treat hypovolemia.

Antimicrobial

medications may be prescribed for the treat-ment of pulmonary infection. This

is a common complication of pulmonary contusion (especially pneumonia in the

contused seg-ment), because the fluid and blood that extravasates into the

alve-olar and interstitial spaces serve as an excellent culture medium.

Related Topics